With Fascination of Plants Day approaching, Botany One has prepared a series of interviews with researchers from around the world working in different areas of botany to share the stories and inspiration behind their careers.

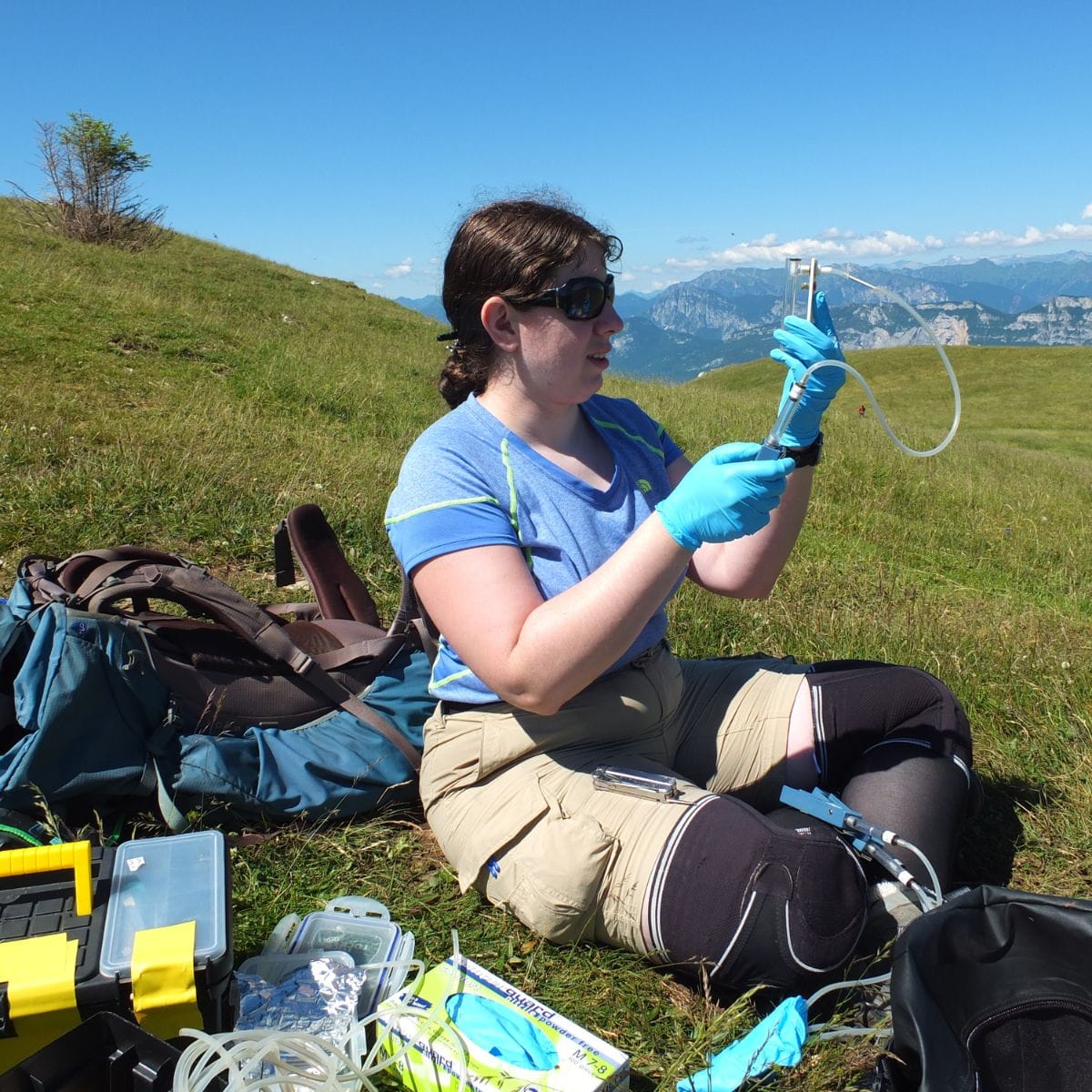

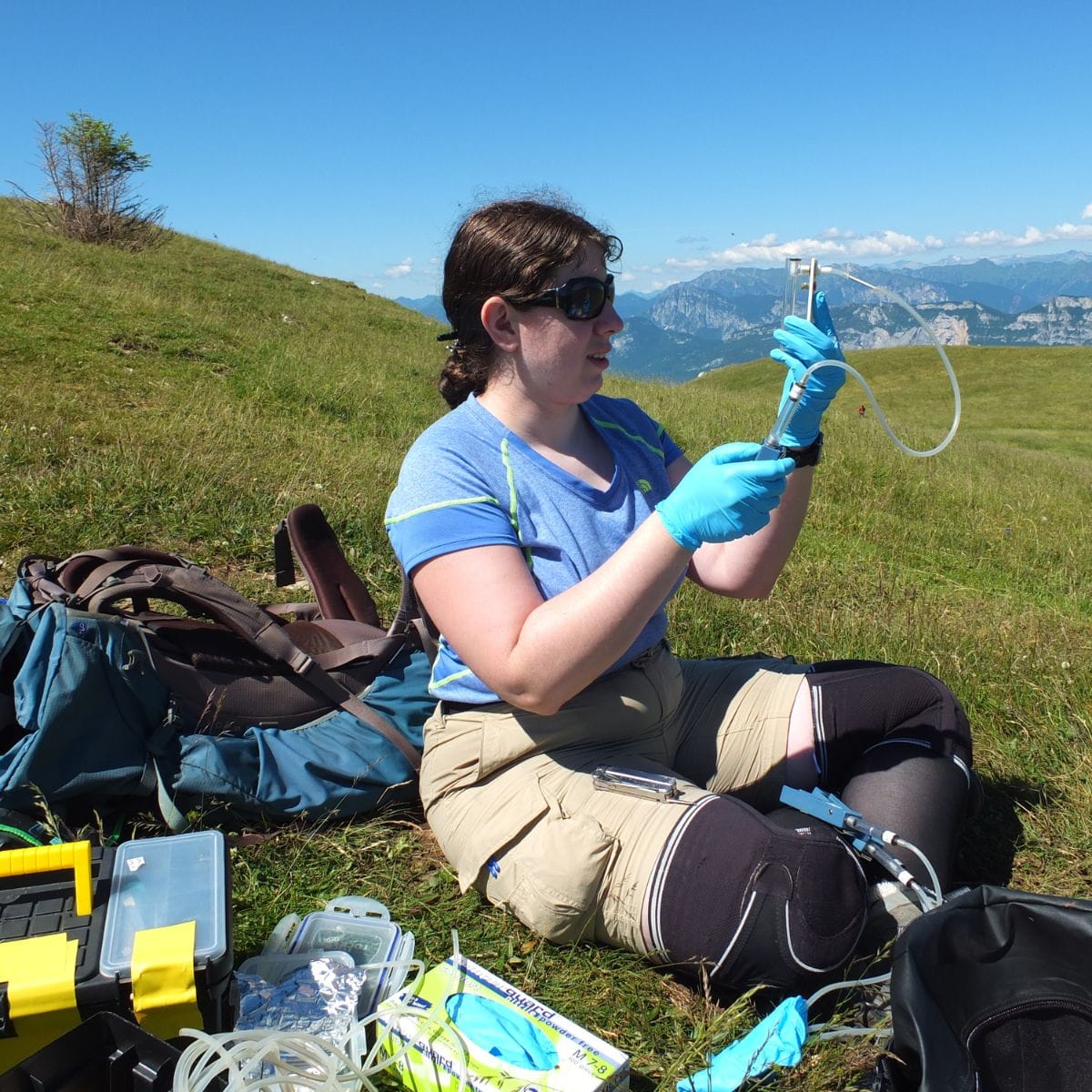

To kick off the series, we have Dr Kelsey J. R. P. Byers, a Group Leader at the John Innes Centre (Norwich, UK). Dr Byers is a queer and disabled ecologist that studies the evolution of floral scent, from the genes that make unique flower aromas to the way flowers use them to attach pollinators. Byers is also an advocate for diversity, equity and inclusion in science, serving as a Co-Chair of the Diversity Committee of the Society for the Study of Evolution. To know more about Dr. Byers research, you can visit her lab’s page and follow her on X and BlueSky as @plantpollinator.

What made you become interested in plants?

Growing up, I ran around the woods a lot – my family home was connected to some federally protected conservation land, and it was really almost wilderness. My mom and stepfather were both scientists, and despite being physicists, they really encouraged my interest in biology. We also had a large garden and rarely needed to buy produce in the summer and fall as a result, so I had plants all around me growing up. There were even orchids (Cypripedium acaule, or Pink Lady’s Slipper) growing in the woods behind my house. I studied genetics and molecular biology at university but wasn’t sure what organism to work on when I started my PhD. By pure chance, I ended up working on plants and fell in love with them and with their pollination systems. My other choice was to work on several species of wild mice, and in retrospect, I’m really glad I work with plants, which are much easier to care for overall and have so many wonderful ecological and evolutionary stories!

What motivated you to pursue your current area of research?

I started working on the colour preference of hawkmoth pollinators in Mimulus monkeyflowers at the beginning of my PhD. After reading the literature, I discovered that the Mimulus must be producing floral scent, despite what my PhD advisor and his collaborator thought, as these hawkmoths will only visit flowers that are the right colour and emit floral scent. My department hired a floral scent biologist at the same time, who became my co-PhD supervisor and taught me loads about floral scent research. Bridging the space between my two labs – one on floral trait genetics and pollination and the other on floral scent chemical ecology and insect olfaction – was an absolute joy and led me to study the genetics and evolutionary chemical ecology of floral scent and its role in plant-insect interactions. Even though I nearly failed my chemistry courses at university, I now love delving into how plants communicate with chemical signals!

What is your favourite part of your work related to plants?

I think my favourite part is learning about the weird and wonderful ways in which plants and pollinators interact. For example, did you know that honeybees (Apis mellifera) are poor pollinators of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) because the flower has a lever-type mechanism that bops the poor honeybee on the head? Alfalfa is best pollinated instead by wild bees, such as the alfalfa leafcutter bee (Megachile rotundata), which fits into the flower better. There are also the wonderful arum flowers (family Araceae, e.g. the Titan Arum, Amorphophallus titanum, or the cuckoo-pint, Arum maculatum), many of which attract insects by pretending to be a good place to lay eggs, for example by mimicking rotting meat or dung. And then there are Dracula orchids, which mimic mushrooms to attract pollinating flies (and there are studies with 3D-printed Dracula flowers showing this!), and Ophrys orchids, which send out the sex pheromones of female bees and wasps and lure in males of the same species! The Ophrys-bee relationship is so specific that single genetic changes can even result in instantaneous switches in whom the pollinator is, which is SUPER neat.

Are any specific plants or species that have intrigued or inspired your research? If so, what are they and why?

I mentioned earlier that in my childhood in the USA, we had wild Pink Lady’s Slippers (Cypripedium acaule) in the woods behind my house. When I was a child, I didn’t even know that it was an orchid, despite my parents telling me that people kept coming to dig it up illegally and sell it. After my PhD, I moved to Switzerland to study European terrestrial Alpine orchids. For some reason, I didn’t even know there were orchids here in Europe, despite having orchids in my own backyard as a child! These orchids (Gymnadenia spp.) are wonderfully smelly (one could honestly bottle them up and sell them as perfume, though I can sadly report that the Body Shop’s “Nigritella” perfume doesn’t smell at all like the real thing!) and the easiest way to tell two look-alike species in the field is by scent – one (G. conopsea) smells like cloves, the other (G. densiflora) like cinnamon. They are pollinated by a range of butterflies and moths and offer nectar in a spur whose walls are so thin you can even see how much nectar is there! The idea that I can (and do) study orchids in the wild is super exciting.

Could you share an experience or anecdote from your work that has marked your career and reaffirmed your fascination with plants?

I was walking to my PhD lab one day when I received a phone call from my supervisor that the Amorphophallus titanum (Titan Arum) was going to bloom that evening. He was away and wanted me to speak to the media about the plant and its ecology and scent. I ended up doing several fun experiments over the next two days, including capturing its floral scent every 90 minutes to see how it changed over time – by 10,000-fold in total scent production over a few hours! It was graduation week at the university, and we had over 3,000 visitors to see the plant blooming, as well as international media attention. It was amazing to see so many members of the public so interested, and I actually lost my voice from giving media interviews and doing public outreach on the handful of days it was flowering! The plant’s ecology is super neat – it mimics carrion to attract pollinators that think it’s dead meat and lay eggs on it – and it only blooms every few years, so it was a really special opportunity to both study it and educate people about it, as well as to smell its terrible stink.

What advice would you give young scientists considering a career in plant biology?

I think one of the most underestimated things is the importance of seeing your organism in its natural habitat, if at all possible. I have learned more from two hours of observing Heliconius butterflies (OK, not a plant, but still) in the wild in Panama than I learned from months of working with captive ones – seeing the organism in its evolutionary and ecological context is huge. I also think that having a basic working knowledge of plant taxonomy and evolution – the former of which I’m sadly a novice in! – is a big plus, both for helping you identify your organism and its evolutionary context, as well as fuelling any free time desires to botanise that you might have. Get to know the natural history of your organism as much as possible – even if you are studying a lab model like Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale Cress) or Marchantia polymorpha (Common Liverwort), there are fascinating things to discover, and you will understand your organism better than you would if you only see it as a model species with no ecology. As much as possible for you, go out, get your hands dirty, and see the world through the plant’s perspective!

What do people usually get wrong about plants?

One big issue we often see with plants is something called Plant Awareness Disparity –sometimes also called “plant blindness”, but I avoid that term as it is problematic from a (dis)ableist perspective by equating blindness with ignorance). Many people don’t think of plants as living beings, or only think of them as the background setting for animals to live in. This leads to problems with conservation efforts, including listing of threatened plants, funding for plant research, and general public perception of plants, especially those that are not seen as immediately useful, e.g. native plants rather than crop species. Folks tend to forget that without plants, we could not survive, nor could most life on our planet! People also often think of plants as immobile, non-active organisms, when the opposite is true – plants can move, communicate with other plants and animals, give resources to their offspring or relatives, and in many ways do things we often think of only animals as able to do! Just because plants lack a ‘typical’ nervous system or brain doesn’t mean they aren’t capable of sensing and responding to their environment or communicating with other organisms, just as animals do.

Carlos A. Ordóñez-Parra

Carlos (he/him) is a Colombian seed ecologist currently doing his PhD at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Belo Horizonte, Brazil) and working as a Science Editor at Botany One and a Social Media Editor at Seed Science Research. You can follow him on X and BlueSky at @caordonezparra.