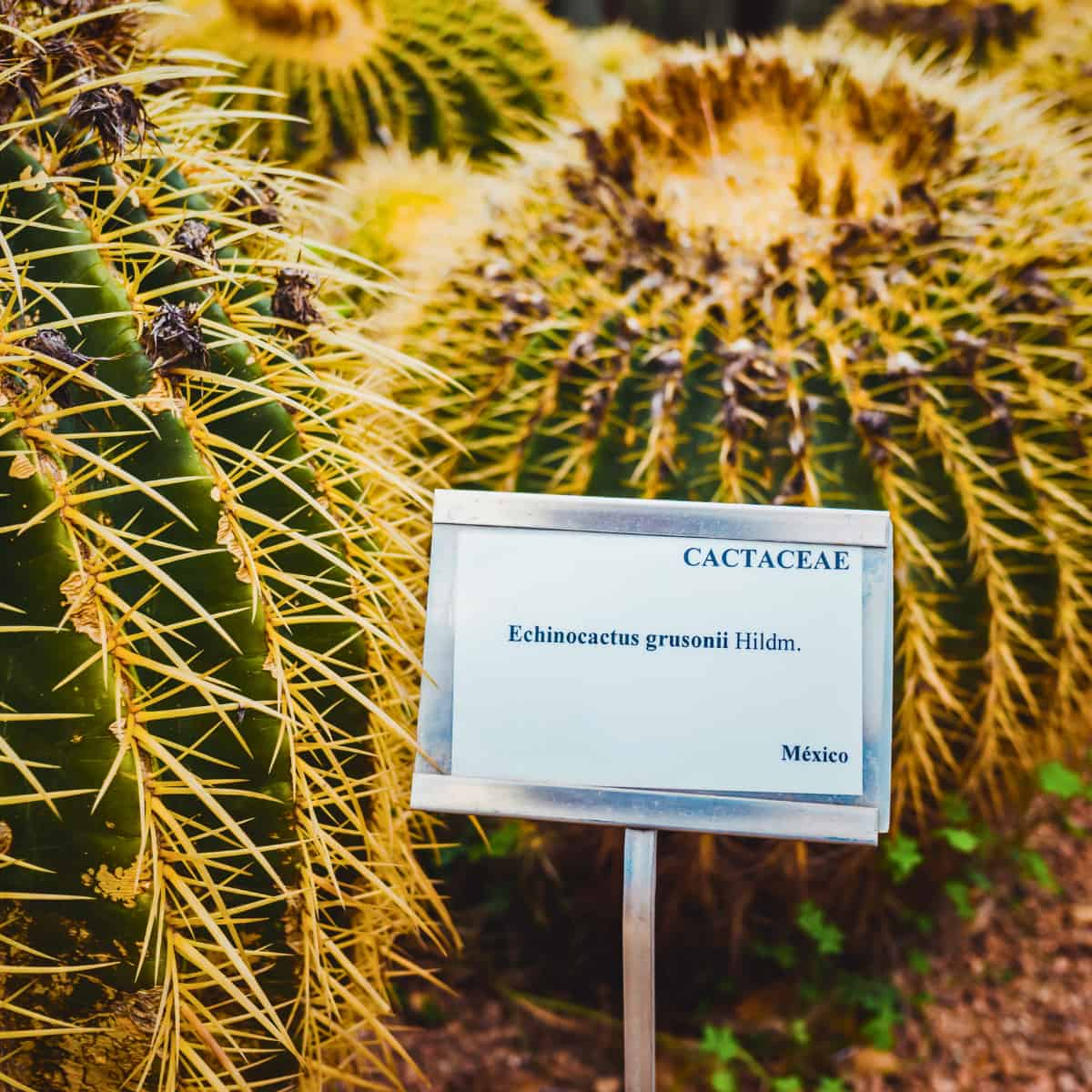

Take a walk through a botanic garden. You’ll see plants and if you look closer, you may see labels associated with the plants. But that small label tells only a fraction of the story. The plants in a botanic garden are in the care of botanists and, just as a hospital needs to know more about their patients than just their name, so too a botanic garden needs to access a wide variety of data about the plants in their care. A recent paper in Nature Plants by seventy authors from 53 botanical institutions makes it clear that’s not a simple task.

Tracking Thousands of Collections That Never Stand Still

The paper opens by stating: “Globally, there are more than 3,500 documented living plant collections, collectively stewarding a staggering minimum of 105,634 plant species, encompassing 30% of all land plant species diversity.” That’s a lot of sites to keep track of. And each site is changing all the time because the key element of botanic gardens is that they host living collections. That means the information can’t be stored away and dealt with when you have time. Each of these 3,500 plant collections is constantly changing as plants grow, mature and die.

On top of that, time is a luxury. Plants around the world, and the communities that live with them, are under threat. Habitats are being lost. Diseases are spreading, and climate change is adding more stress to ecosystems challenged by invasive species. So information is needed now. Are gardens that are thought to be safeguarding endangered plants still a safe refuge? Do they even know what threatened species they’re holding? The answer depends on whether they can access and share their data. Right now, many gardens can’t.

Why can’t gardens share their data?

It’s 2026. Can’t we get computers talking to each other to share data? For up to two thirds of botanical collections worldwide, first you’d have to get the records into a computer. Most places still have their records on paper. Even for the sites with digital systems, there’s no agreement on what the databases should look like, which means that there’s no common format database and no easy way to transfer information.

This lack of transfer isn’t just a nuisance. It’s a disaster waiting to happen. A new assessment by the International Union for Conservation of Nature might place a species on their Red List. That could make a collection of plants at a botanic garden critical for survival of the species. But if the garden doesn’t realise that new data has made their plants much more valuable, they might be lost so that budgets can be spent on other priorities.

It’s a challenge because living collections constantly generate so much data. From the moment a plant enters a garden, information accumulates: Was it collected from the wild and, if so, when, where and by whom? Was it legally obtained? Once it’s in the garden, you still need to know if it’s healthy, how mature it is, whether or not it’s damaged and, so you can actually check, where in the garden it is. And when it’s de-accessioned, how did it leave? Was it transferred to another garden? Or did it die, and if it did, what was the cause of death?

Without standardised, connected systems, this rich information becomes trapped in individual gardens. In a press release lead author, Professor Samuel Brockington said: “We’ve built an extraordinary global network of living plant collections, but we’re trying to run twenty-first-century conservation with data systems that are fragmented, fragile, and in many cases inaccessible to scientists and conservationists working where most biodiversity originates. We urgently need a shared data system so the people managing collections can work together as a coordinated whole.”

What would a global system work like?

Brockington and colleagues argue that any global system has to be built on cultural change. They write: “Botanic gardens often struggle with transparency regarding the contents and provenance of their living collections, with its origins in a historical culture of competitive collecting practices.” This, they argue, has to be put aside and data made open to build trust between participants.

With open records, local databases held at gardens could exchange data with global databases and each other. They identify six key principles. Records should be: Open (searchable by stakeholders), Accessible (the linked material available for use), Accurate (up-to-date and taxonomically current), Compliant (meeting legal standards), Standard (using common formats for integration), and Secure (preserved for the long term). They write: “By prioritizing accessibility, particularly for currently undigitized collections in the Global South, we aim to ensure equitable participation in the global conservation effort.”

A standard data format would enable seamless updates. World Flora Online could push the latest taxonomic revisions to all gardens. IUCN threat assessments would automatically flag endangered species in collections. These updates in turn could help conservationists source diverse seeds for a re-introduction of plants to restored areas.

Thaís Hidalgo de Almeida, of the Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro and a co-author of the report, said: “Having an integrated and equitable global data ecosystem would greatly help us address urgent conservation needs in biodiversity-rich countries like Brazil, making our work faster, more collaborative, and more effective.” It’s a vision grounded in proven approaches from other collaborative conservation networks.

Collaboration in progress

BGCI, Botanic Gardens Conservation International, already has PlantSearch. This allows you to search for a plant among gardens. So for example, if you were looking for Drosera capensis, you could see which 95 gardens have it. If you were looking for Drosera capensis L. ‘Alba’, then you’d find there were 12 gardens holding it.

BGCI also coordinates the Global Conservation Consortia. These are groups of institutions and experts that work together to help preserve certain plants. Recently Linsky and colleagues evaluated the work of three consortia conserving cycads, magnolias, and oaks. Pulling together multiple holders of oaks has allowed conservationists to plant groves of genetically diverse oaks which, it is hoped, will have more resilience in the face of future challenges than a single-source population would have.

These successes show that coordinated data systems deliver real conservation outcomes, but Brockington and colleagues argue the infrastructure needs to go further. They write: “Although repositories such as BGCI’s PlantSearch collate data on the contents of living collections, these data are not integrated with individual collections with sufficient frequency, and consequently botanic-garden-derived data in global repositories are patchy and out of date.”

They also give examples of similar work in other fields that show their vision is achievable. They write: “Initiatives such as iDigBio in the USA have successfully mobilized hundreds of millions of preserved specimen records into a unified digital resource, whereas DiSSCo in Europe are building distributed infrastructures to integrate diverse natural science collections within a common data framework.” They also mention GENESYS as an example that even living collections can be networked globally. This database pulls together the material held in genebanks, showing that collections need not be static to work in a global system.

What could we gain?

It might be hard to believe, if you live somewhere where you can see plenty of plants, but around 40% of plant species are at risk of extinction. That doesn’t mean 40% of plants are going to become extinct imminently. But it does mean that disaster could strike anywhere in a wide range of plants, meaning you need eyes on everything. Each botanic garden is a potential life raft but, without connection to other gardens, any hope of rescue for a species may be lost through isolation.

Making things worse, each life raft is facing a series of impending waves. Climate change is changing conditions faster than some species can migrate. Knowing where plants are thriving ex situ, outside their natural environment, could help identify new locations to aid with assisted migration. At the same time, gardens could also check that species aren’t thriving too well and risk becoming invasive species.

Up-to-date, connected data would also amplify early warning systems. The International Plant Sentinel Network tracks the health of ex situ plants and records their vulnerability to pests and pathogens, allowing advance warning of the risks of spreading diseases. A unified system would make these alerts faster and more comprehensive.

Paul Smith, Secretary-General, BGCI and a co-author of the report, said: “In an era of accelerating biodiversity loss, harnessing the full conservation potential of living collections requires a step-change in how collections data are documented, standardised and connected through a global data ecosystem.”

Many botanists believe that it is possible plant extinctions could become a thing of the past. But achieving this requires understanding how well species are doing, and for that we need a global view. If Brockington and colleagues achieve their goal, the next time you see a label in a botanic garden, it will mark more than the location of a single plant. It will be a connection to other plants across the planet.

READ THE ARTICLE

Brockington, S.F., Malcolm, P., Aiello, A.S., Almeida, T.H., Apple, M., Aragón-Rodríguez, S., Arbour, T.P., Barreiro, G., Phillips-Bernal, J.F., Borsch, T., Cano, A., Choo, T., Coffey, E.E.D., Crowley, D., Deverell, R., Demissew, S., Dempewolf, H., Diazgranados, M., Falcón-Hidalgo, B., Franczyk, J., Freeth, T., Freid, E., Gale, S.W., Griffith, M.P., Güntsch, A., Hart, C., Hearsum, J., Hollingsworth, P.M., Justice, D., Kirkwood, D., Khoury, C.K., Knapp, W.M., Kool, A., Koski, J., Kum, T., Niu, Y., Löhne, C., Lupton, D.A., Magombo, Z., Manrique, E., Martín, M.P., Martinelli, G., McGinnis, D., Neale, J.R., Newman, P., Novy, A., Park, T., Pell, S., Pirie, M.D., Puente-Martinez, R., Ren, H., Reynders, M., Rodríguez-Cerón, N., Rønsted, N., Schoenenberger, N., Senekal, A.M., Sucher, R., Summerell, B., Summers, A., Tan, P.Y., Tornevall, H., Walsh, S.K., Washburn, C., Wiland-Szymańska, J., Wang, Q.-F., Willis, C., Wyatt, A., Wyse Jackson, P., Yu, W.-B. and Smith, P. (2026) “High-performance living plant collections require a globally integrated data ecosystem to meet twenty-first-century challenges,” Nature Plants. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02192-6.

Read free via ReadCube: https://rdcu.be/eYlEi