What happens when an entire region calls an endangered tree by the wrong name for 20 years? This happened on Cofre de Perote Mountain, around 200 km east of Mexico City. It’s here you can find the endangered tree Abies hickelii. It’s known as Hickel’s Fir, in English but locally the tree is known as ‘Oyamel’. If you decide to go looking for it, then you’ll need careful eyes, because it looks similar to Abies religiosa, another fir that grows on the same mountain. It’s known in English as Sacred Fir. This is not an endangered tree, it’s the most widespread tree in Mexico and Central America. But while this tree looks similar to the endangered tree, it doesn’t have a similar name. It’s worse than that, it has the same name. It’s called ‘Oyamel’, just like the endangered tree.

At Cofre de Perote Abies religiosa, the common tree, is logged and is an important source of timber. Abies hickelii, being endangered, should be protected. You’re probably seeing where this is headed, but it’s not that simple. Vázquez-Ramírez and colleagues studied this site and certainly found logging of endangered trees, but the same confusion also worked to increase plant numbers.

How can you confuse an endangered tree with a common tree?

The critical factor here is that this confusion isn’t due to laziness, or wilful and profitable ignorance. The trees are genuinely difficult to tell apart. Scientists have being arguing about their taxonomy, the method of classifying them as one species or another. In 2009, Strandby and colleagues argued that Abies hickelii should be considered a subspecies of Abies religiosa. The two trees can interbreed to create hybrids.

Vázquez-Ramírez and colleagues include details of differences between the trees. Some are clear differences, like the leaves on Abies hickelii having four to eight resin canals, compared to Abies religiosa’s two. Another difference is that the seed cones of Abies hickelii are smaller. Other differences are real, but unhelpful when you’re on site. Abies hickelii has smaller seeds, on average. They’re between 4-9 mm long. Abies religiosa seeds are, in comparison, 5-10 mm long. That’s a measurable difference, but the overlap means that any individual seed is going to be difficult to identify.

The easiest way to tell them apart is to know what side of the mountain you’re on. Abies hickelii grows on the windward side of the mountain, between 2700 and 3200 metres above sea level. Abies religiosa grows on the leeward side of the mountain between 3100 and 3600 metres above sea level. This is helpful if you know there are two different species, but if they’re all Oyamel, and they look the same, why would you think one was endangered?

Vázquez-Ramírez and colleagues found that there was confusion while working on a conservation project. Seeing that there was an understandable problem, they tried to see how local interacted with the trees, and found some unexpected benefits. They write: “Through interviews with local communities on the Cofre de Perote Mtn., we found that some had been collecting Abies seeds from trees within the range of A. hickelii for more than 20 years. These seeds were later sold as A. religiosa to nurseries supplying saplings to government reforestation programmes, which aim to restore degraded forests and support rural livelihoods.”

The Good

The team went searching through the paper trail to see what happened to the seeds, looking for records of seed purchases from the Mexican National Forestry Commission and the Veracruz State Environmental Office. These agencies were administering reforestation programmes. So, by trying to find seeds collected from areas where only Abies hickelii grows, they could see what happened to the plants. They write:

“The Mexican National Forestry Commission (hereafter Forestry Commission) reported that 14.9 million Abies seeds were purchased from the specified locations between 2006 and 2018. However, all seeds were recorded as A. religiosa, with no mention of A. hickelii. The reported mean viability of the seed lots was 56.2%. Although the records did not specify which nurseries received the seeds, we estimate that up to 8.4 million seedlings of A. hickelii may have been unknowingly grown and distributed through reforestation programmes, based on seed quantity and reported viability.”

Following through on this, the team ended up visiting reforestation sites, and examining the trees. According to the paperwork, all the trees were Abies religiosa. However, at two of the three sites, Vázquez-Ramírez and colleagues found that people had planted Abies hickelii. The taxonomic confusion has resulted in a verified increase in the population of the endangered Abies hickelii by at least 30 000 trees at the sites they visited, with potentially millions more distributed elsewhere. But it’s not all good news.

The Bad

Vázquez-Ramírez and colleagues also examined logging in the area. They make clear logging is permitted in the community forests, but there is a need to get permissions for the endangered species. But, given no one recognised that there were any endangered plants there, no one did.

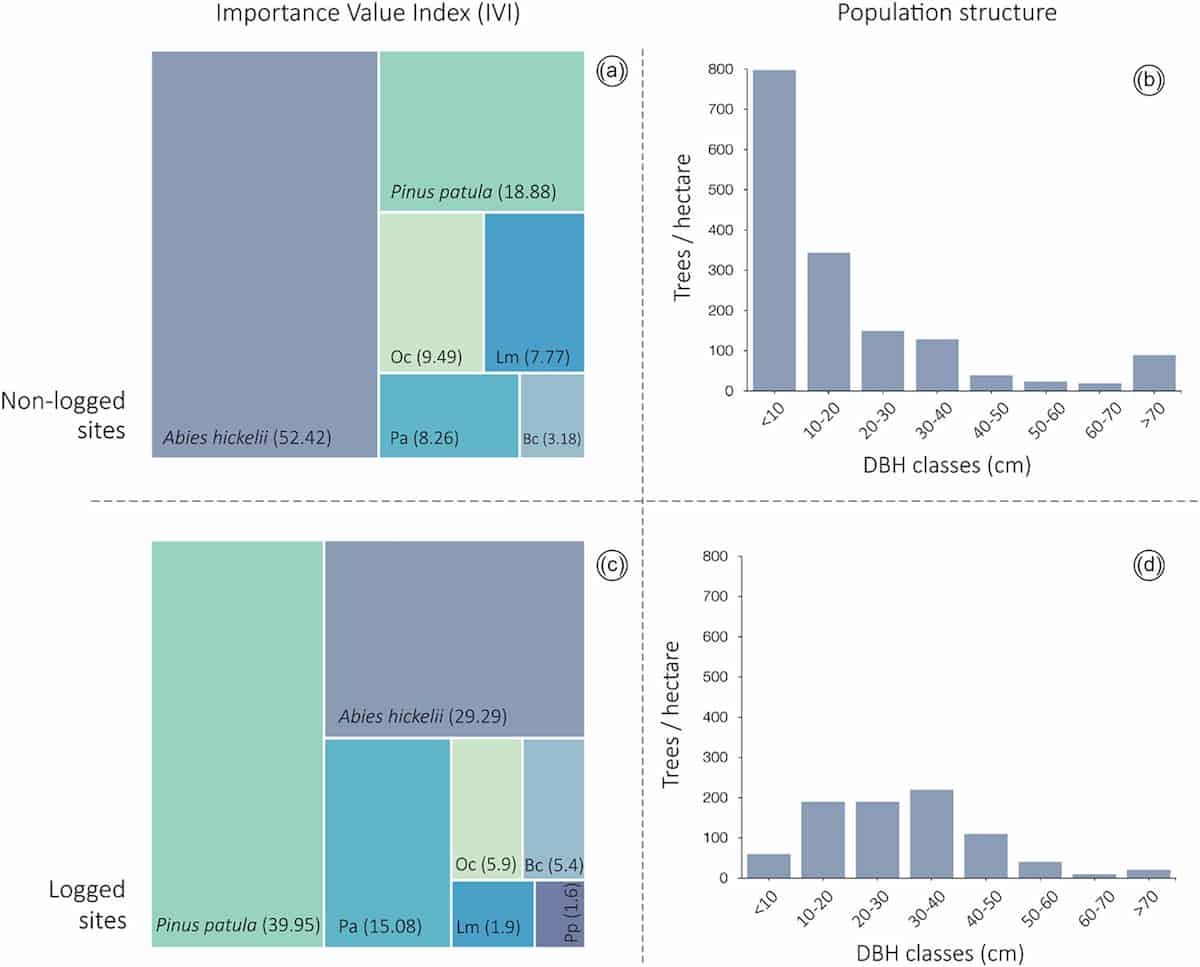

The team compared logged and unlogged plots to see what happened to the Abies hickelii trees in the area. In the unlogged plots, Abies hickelii was the dominant tree in the ecosystem. The demographics had a distinctive distribution, with many young trees and progressively fewer older trees, the classic pyramid shape of a healthy, self-sustaining forest.

In the logged areas, Pinus patula, Jelecote Pine, became the dominant species. More worrying, the demographics of Abies hickelii changed dramatically. There are only half as many mature trees, and dramatically fewer young trees, only 3% of the number found in similar healthy plots. That lack of young trees tells us that things are only going to get worse for Abies hickelii in the logged plots, as the population can’t replace itself.

The Ugly

The findings mean that people working with the trees in the region have an unexpected legal headache. The trees they thought were ordinary trees, are legally classified as endangered and that brings a lot of paperwork. Vázquez-Ramírez and colleagues found out that wasn’t being done at the moment. They write:

“To assess whether A. hickelii was being legally managed, we submitted an anonymous information request through the Mexican Transparency Institute for records of species managed under registered UMAs in the study region. The authorities reported no records of A. hickelii, confirming that communities, forestry technicians, and government officers had been involved in its use (e.g., seed collection, plant production) and exploitation (e.g., logging) without the required legal authorization.”

This isn’t intentional lawbreaking. Communities, forestry technicians, and government inspectors all believed they were following the rules for common Abies religiosa. However, they were accidentally violating endangered species protections. If this is now corrected, then communities will have a lot of new bureaucratic and financial burdens, getting permits to do exactly what they’ve been doing all along. This illustrates the point Vázquez-Ramírez and colleagues make in their conclusion.

What can we learn?

The authors emphasise the importance of taxonomy throughout the conservation process. Taxonomy can be considered an academic problem and not a practical issue. In the case of the seedlings, the Mexican Forestry Commission now purchases seed lots from certified stands. That means that the trees have been verified as belonging to the species people think they are. However, the logging permits remain a problem.

The logging permits rely on people not getting confused between common Oyamel and endangered Oyamel. If people confuse Oyamel with Oyamel, or don’t realise there’s a difference, then the logging permits, sincerely applied for, aren’t doing their job of protecting the rare trees. Vázquez-Ramírez and colleagues argue that taxonomic expertise is needed at each step of the conservation process, so that practitioners can be sure their efforts are going to the species that need help. They write:

“Bridging the gap between taxonomy and applied conservation is essential to ensure that protected species are correctly identified, appropriately managed, and legally safeguarded. Our case study highlights a key lesson for taxonomists and conservation practitioners worldwide: the success of biodiversity policy depends not only on sound taxonomic science, but also on the systematic integration of taxonomic expertise at every stage of biodiversity management.”

The accidental success of spreading Abies hickelii in new reforestation projects shows the desire to conserve forests is there. Giving people access to taxonomic expertise would give people the ability to use their effort more effectively.

READ THE ARTICLE

Vázquez-Ramírez, J., Narave Flores, H.V. and Cházaro Basañez, M.J. (2025) “Unexpected consequences of taxonomic misidentification for the conservation of an endangered species,” Conservation Science and Practice, (e70180). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.70180

Cover image: Examining Abies hickelii near Cofre de Perote by pronaturaveracruz_zonastempladas / INaturalist. CC-BY-NC.