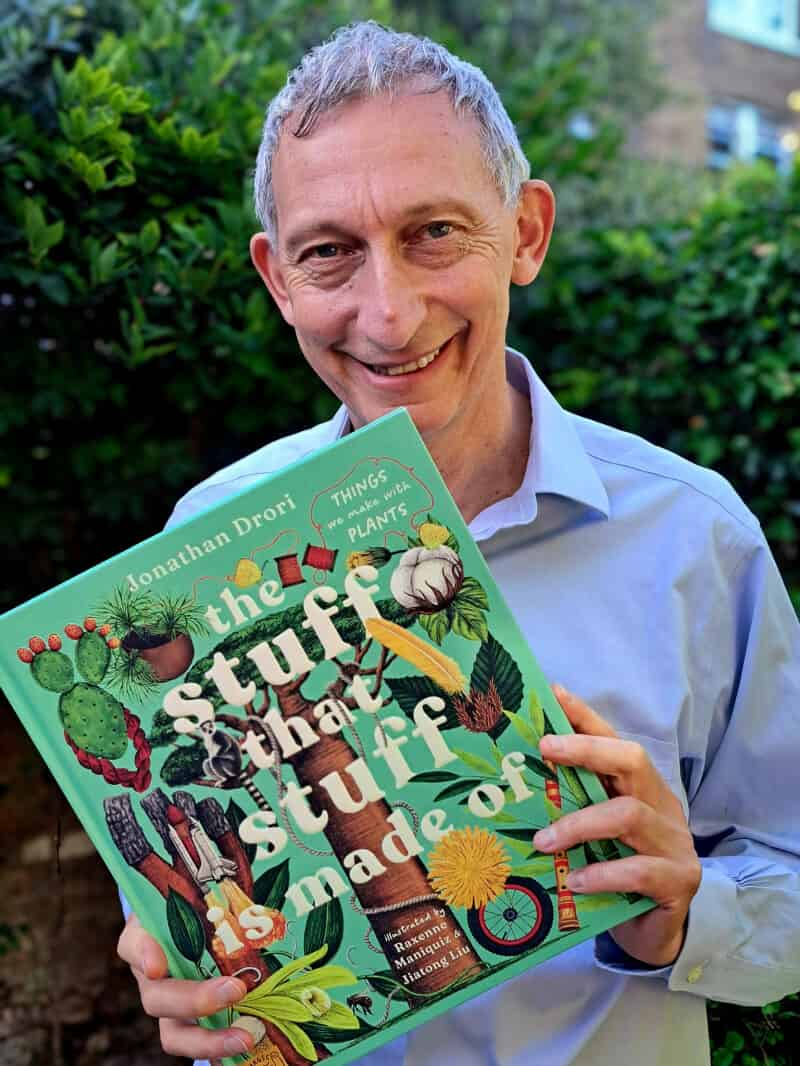

The Stuff That Stuff Is Made Of is a new book from Jonathan Drori that, if successful, could help grow the next generation of botanists, being aimed at children seven years old and up. If you’re familiar with the name of the author, it may be from his earlier books, Around the World in 80 Plants and Around the World in 80 Trees. This is in some ways a similar book, being another collection of plants. This time, the connection is that all the plants are used to make things. In other ways, it is quite different – which is just as well as this is also a different audience.

The book is just over 26 cm wide and almost 32 cm tall. Despite being hardback, it’s also a light book thanks to is 64 pages. So while it’s the perfect size and shape for swatting an annoying sibling, it shouldn’t do too much damage when it impacts. The cover is also a pleasing texture with the title and some of the plants embossed, raising your fingertips as you brush them over the cover. This might seem an odd point for a book review but, given the target audience, the reader will receive this book as a gift. The publishers have done an excellent job in making this a desirable object. I think that’s a critical step in making this a book that someone would want to come back to, and at this age books are read again and again and again.

The book opens with an Introduction, before moving on to thirty plants, each covered across a spread of two pages. I haven’t sat down to word count the whole book, but I get the impression this Introduction, on just one page, may have more words than any of the chapters. In it Drori covers his personal discovery of plants, and then explains his view of why plants are important, their practical value, their social effects (of which more in a moment), and lastly the fact they’re simply interesting.

There’s a question of which thirty plants you could pick and, in his review, Nigel Chaffey has given a breakdown of the selection of plants. They’re mainly angiosperms, introduced with the scientific names, except Pinus and Cotton which are both listed just a genus and Pumpkin, which is introduced as being of the Cucurbit family. The plants also have page numbers in the index, which is good if you want to find them, because they’re not presented in alphabetical order.

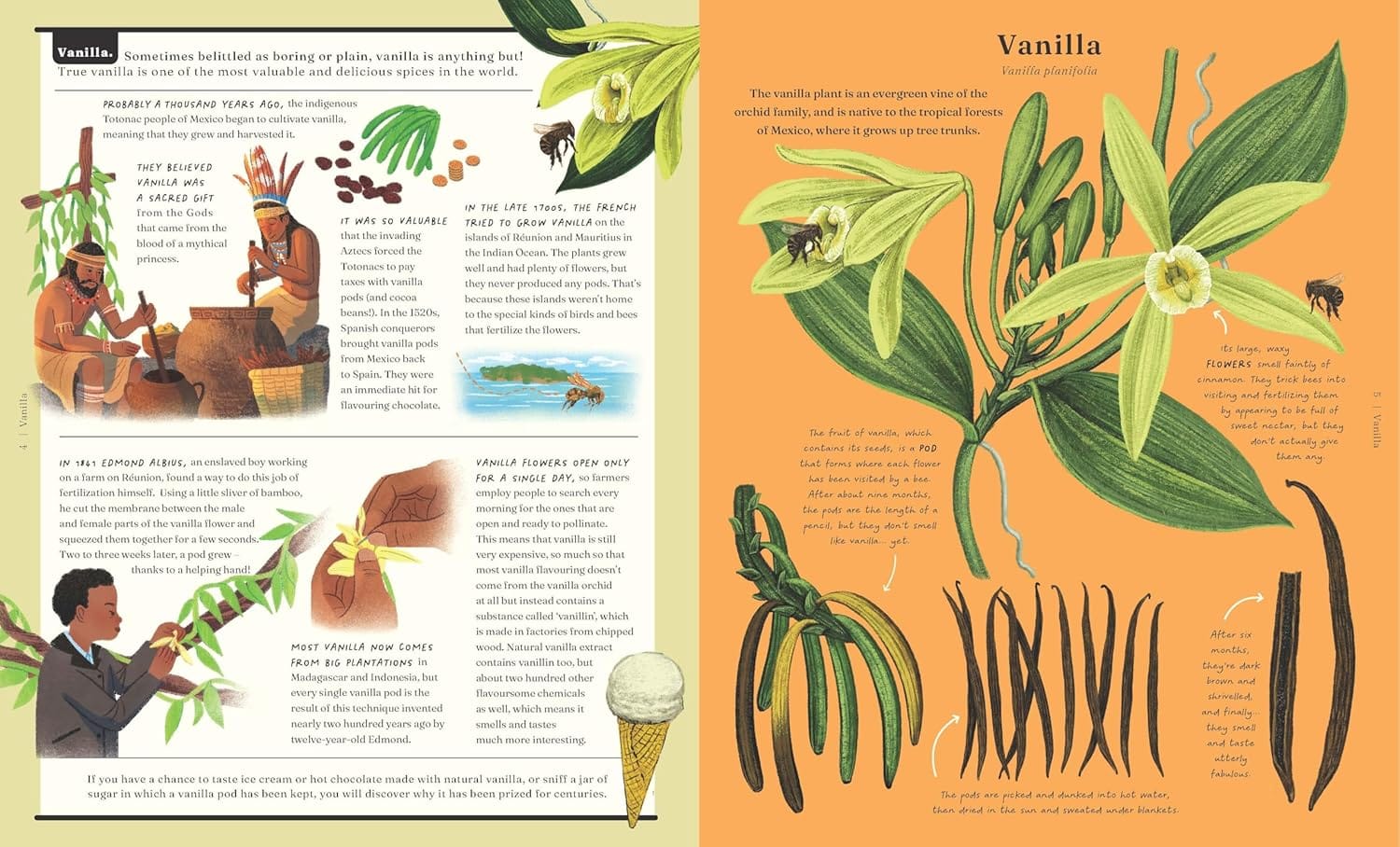

The order of the plants interests me because with a book that’s a collection of plants, there isn’t an obvious order. So I imagine that there’s a great deal of thought gone into this, and the opening plant Vanilla, was an excellent choice.

In many ways Vanilla embodies the problem Botany has. As the opening points out, the plant is a synonym for plain or dull, yet in just two pages Drori hits so many of the strengths of this book. The section starts off with the Aztecs and explains how conquered peoples would have to pay taxes in Vanilla pods. He mentions the cultivation of orchids on Reunion and Mauritius and how despite growing well, they failed to produce valuable pods. I like how this neatly and succinctly plants the idea of pollination and ecology in just a few words. He then moves on to how pollination was solved, thanks to Edmond Albius who, at the age of twelve and as a slave, worked out how to pollinate Vanilla artificially.

This is where I was won over by the book. At the very first plant Drori shows the young reader that children can be plant experts. The role model is right there. I also think that Drori acknowledging Albius was a slave is also important. A lot of practical plant problems cannot be sensibly discussed without reference to economics, and likewise the economic history of many plants is entwined with slavery. Not surprisingly, this comes up again with other plants grown on plantations.

The text on the left page is broken up by some colourful and attractive art. On the right page is a picture of the plant, with supporting text around it. This balance of text and art is the template for each plant in the book. I’m envious of the skill of the artists, but then again I’ve not met a botanical artist whose skill I haven’t envied.

The next four plants in the book are Tea, which is another mundane product with an interesting history and biology, Mandrake, Papyrus, which offers more than paper, and Theobroma cacao, which makes chocolate. All of these are commonplace products that children will be familiar with. The apparent exception, Mandrake, will be familiar to any child with a love of Harry Potter.

The plants that follow are a mix of the familiar and the exotic, though which are familiar and which are exotic depends on where you’re reading the book. The common element is that even when the plant is exotic, the product it creates is very familiar. The book closes with the copyright page, and a brief glossary.

The glossary is possibly the only weak part of the book. To be fair, I’m not sure what a strong glossary would look like. It’s the only place where Jonathan Drori’s personality doesn’t come through, with brief definitions of select terms used in the book

That’s important because everywhere else there’s a real warmth to the book, not just for the topic but also for the reader. It doesn’t read like an educational book lecturing the reader, rather it’s more a friend sharing something they’re excited about.

The brevity of the chapters works well, as does the brevity of the paragraphs. It keeps the text focussed on the point being made, and keeps the pages from being daunting slabs of text. For younger children the short sections make this work as a read-aloud book for a parent. But for children moving from guided reading to reading themselves, this feels like an achievable read.

The text shouldn’t be a pain for parents to read with their children if they want to. It’s full of interesting material. And I know that it’s a book for children, but when I got the final plant, Peanut, I was disappointed that there wasn’t more to read. The chapter ends with Peanut’s trick of burying the seed pods to allow the next generation to flourish. If this book gets the readership it deserves, it’s going to nurture the next generation of botanists.

The Stuff That Stuff is Made From is published by Magic Cat Publishing and is out now for £16.99 for a hardback. There is an ebook version available in the US, but the price difference is tiny and the illustrations should be lingered over at full size. Get the hardback as a Christmas present for someone small.