Plants are incredibly diverse, and so are botanists! In its mission to spread fascinating stories about the plant world, Botany One also introduces you to the scientists behind these great stories.

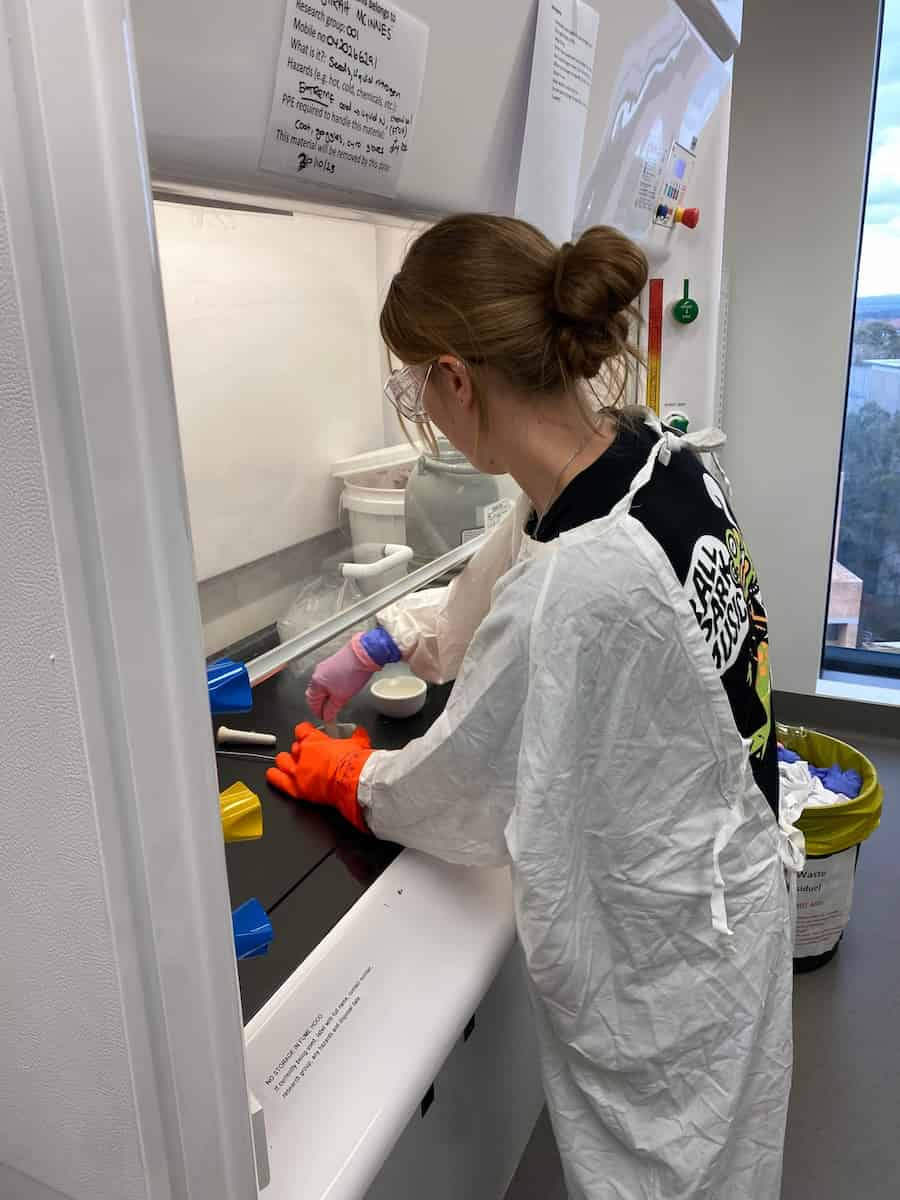

Today, we have Sarah McInnes, a fire ecologist who uses molecular techniques to explore plant persistence in fire-prone ecosystems. She recently submitted her PhD thesis and works within the Threatened, Rare, Endemic (TRE) plant ecology research group at the University of New South Wales, Australia. Her research focuses on the molecular mechanisms used by seeds to survive extreme heat from the passage of fire, and how different fire regimes shape seed trait expression. You can follow her on Bluesky at seedysarah.bsky.social

What made you become interested in plants?

I’ve always loved plants, and a lot of my earliest memories revolve around them. I remember being about six years old and walking with my grandmother around her beautiful garden. She’d always let me take home a basket of flowers whenever I was there, which I loved! Growing up in Australia, I was also very fortunate to be surrounded by pristine bushland and native vegetation. My dad would frequently take my siblings and I camping on weekends, where we’d run wildly about in the bush. Thankfully, we never got bitten by snakes! My mum is also an avid gardener, so I spent a lot of weekends outside helping her in the garden.

What motivated you to pursue your current area of research?

It took an extremely drastic event, the Australian Black Summer bushfires of 2019-20, to make me reassess where I wanted to devote my time and effort. Through this event, I realised that I was concerned about plants and how they recover after a wildfire. I was studying chemistry at the time (no plants at all!), and I remember scouring the university directory to find plant scientists to work with. I was lucky enough to find Scientia Associate Professor Mark Ooi. Mark is a fire ecologist who works on a wide range of plant responses to wildfire and, thankfully, agreed to take me on board for an Honours project. We used my laboratory experience and chemistry background to take a molecular ecology approach to fire ecology – specifically looking at the molecular basis of seed persistence during fire. I continued researching seed persistence in fire-prone ecosystems during my PhD using this multidisciplinary approach, and have generated some very novel, bizarre, and fascinating results!

What is your favourite part of your work related to plants?

There’s an incredible diversity in plants globally, but I especially love learning about how fire acts in different ecosystems and the immense diversity of fire-prone ecosystems. Fire-prone regions are sometimes considered niche, but they are globally distributed! This wide distribution across many vegetation communities has created all sorts of interesting plant persistence strategies through fire. One of my favourite examples is from the Brazilian Cerrado savanna, where flowering has been recorded in Bulbostylis paradoxa less than 24 hours after a fire occurs. While I haven’t yet managed to make it to the Cerrado, I’ve been fortunate enough to see the savannas of northern Australia and the Jarrah Forests of southwestern Australia. Fire behaves very differently in these ecosystems compared to the southern Australian temperate forests where my work is predominantly focused, creating some truly spectacular landscapes that have been shaped by a long history of fire.

Are any specific plants or species that have intrigued or inspired your research? If so, what are they and why?

It’s hard to pick just one! However, one of the first plant species I learned about when I started in fire ecology was Eucalyptus regnans (or Mountain Ash), and it has fascinated me ever since. E. regnans is the tallest flowering tree and the second-tallest tree in the world. Native to the cooler and wetter forests of southern Australia, what makes this species so fascinating is its relationship with fire. Mountain ash forests burn at high to extreme intensity every 75-100 years, generally killing the adult trees during such an event. However, the trees release seeds during this process, which then germinate after the fire. These seeds are only up to 3 millimetres long, yet they grow into trees that can reach heights up to 100m! This remarkable persistence strategy and the power of such small seeds got me hooked on fire ecology – particularly the seed ecology of fire-prone ecosystems!

Could you share an experience or anecdote from your work that has marked your career and reaffirmed your fascination with plants?

Earlier this year, I was fortunate enough to be a demonstrator on a university fieldwork course where we taught undergraduate students plant surveying techniques. It was rainy and humid, and very spiky Acacia ulicifolia was everywhere. Despite this, every student was enthusiastic and keen, and genuinely wanted to know more about plants and their interactions with fire. Being able to share my own passion with these like-mind individuals was incredibly rewarding. I also got to see how much my own knowledge had developed over the years, as I didn’t initially come from a plant ecology background when I started in research. This experience of sharing my passion about plants reaffirmed my love of them and made me realise just how I far had come on my personal scientific journey.

What advice would you give young scientists considering a career in plant biology?

Know where your expertise fits! While the vastness of scientific knowledge can be overwhelming, it’s okay not to know everything (and anyone who says they do is lying). This is where collaborations become important, as collaborators can help to fill the gaps in your own knowledge. Don’t be afraid to reach out to the people around you and ask questions – they can often answer something in minutes that you’ve been agonising over for a week. The other advice I’d give is to follow interesting questions. Science can be a big workload sometimes, so being passionate about what you’re researching is important for maintaining your work ethic (and sanity!) during the busier times. Finally, I would say to never give up! If you want to study plant biology, you will find a way to get there.

What do people usually get wrong about plants?

That within fire-prone ecosystems, plants are adapted to fire itself! Many plants have adapted to specific kinds of fire over time (collectively known as the ‘fire regime’), which can make changes in the fire regime problematic for the overall persistence of those species. The remarkable complexity of plants is also often missed by non-plant enthusiasts, but plants are wonderful and intriguing. One of my favourite stories is about J.R.R. Tolkien (who famously authored The Lord of the Rings), where he would often stop and just stare at trees during walks. I think we could all benefit from taking a leaf out of his book, because when you really stop and look, you’ll be amazed by what you can see.

Carlos A. Ordóñez-Parra

Carlos (he/him) is a Colombian seed ecologist currently doing his PhD at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Belo Horizonte, Brazil) and working as a Science Editor at Botany One and a Communications Officer at the International Society for Seed Science. You can follow him on BlueSky at @caordonezparra.