Plants are incredibly diverse, and so are botanists! In its mission to spread fascinating stories about the plant world, Botany One also introduces you to the scientists behind these great stories.

Today, we have Dr. Patricia Silva-Flores, a Chilean Assistant Professor at the Centro de Investigación de Estudios Avanzados del Maule (CIEAM), Universidad Católica del Maule in Talca, Chile. She leads the Fungal and Mycorrhizal Ecology group, whose research focuses on plant–fungal symbioses, fungal and mycorrhizal diversity, ecological restoration, sustainable agriculture, and art–science intersections. Silva-Flores’s work bridges basic and applied science through interdisciplinary projects developed across Latin America and Europe. As a passionate mentor and outreach scientist, she integrates student training and public engagement into every stage of the research process. Moreover, she currently serves as Director of Communications and board member of the International Mycorrhiza Society (IMS), and collaborate with global initiatives such as the South American Mycorrhizal Research Network and the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN). With a PhD in Botany, an MSc in Evolution, Ecology and Systematics, and a Biology degree, her academic path has taken Silva-Flores through several countries, always advocating for fungi and mycorrhizas as key components of natural systems. You can follow her work at @silvafloresdra.

What made you become interested in plants?

My interest in plants started when I began studying biology and discovered the fascinating flora of Central Chile’s sclerophyllous forest. I was amazed to learn it holds such high plant endemism, many of its species exist nowhere else in the world. At the same time, I was struck by how threatened this unique ecosystem is due to human activity. We were destroying something irreplaceable.

Although I first joined an aquatic ecology lab, driven by my curiosity for ecological questions, my path shifted when I began searching for a research focus that was both underexplored and something I felt truly passionate about. That’s when fungi, and especially mycorrhizal fungi, found me.

I became captivated by mycorrhizas, the symbiotic relationships between plant roots and fungal hyphae. That connection naturally brought me back to plants, but this time through the lens of underground interactions. Everything clicked. I decided to focus my research on the ecology of mycorrhizal fungi in sclerophyllous forests, always with the goal of contributing to the conservation and restoration of this unique biodiversity hotspot.

What motivated you to pursue your current area of research?

What truly motivated me was the lack of research and knowledge around mycorrhizas and mycorrhizal fungi, a key symbiosis and key organisms for the functioning of natural ecosystems of my country. Conservation and restoration efforts in terrestrial ecosystems, like the sclerophyllous forest, have traditionally focused only on plants, while the symbiotic fungi supporting them were often overlooked. Taking on that challenge felt deeply important to me.

At the same time, I find fungi absolutely beautiful and full of teachings — not only scientific, but also philosophical, artistic, ecosocial, and educational. They invite us to think in new ways. That richness feeds my curiosity and keeps me inspired every day, not just as a scientist, but as a person.

What is your favourite part of your work related to plants?

I have two favorite parts. The first is going out into the field to collect samples and entering the forest, which has always welcomed me so kindly. Being there, surrounded by the scents of different plants, the variety of leaf shapes, the shades of green, the temperature, the smell of the soil, of the fungi… it’s an indescribable and enriching experience, absolutely poetic. You can only truly understand it when you’re in the forest.

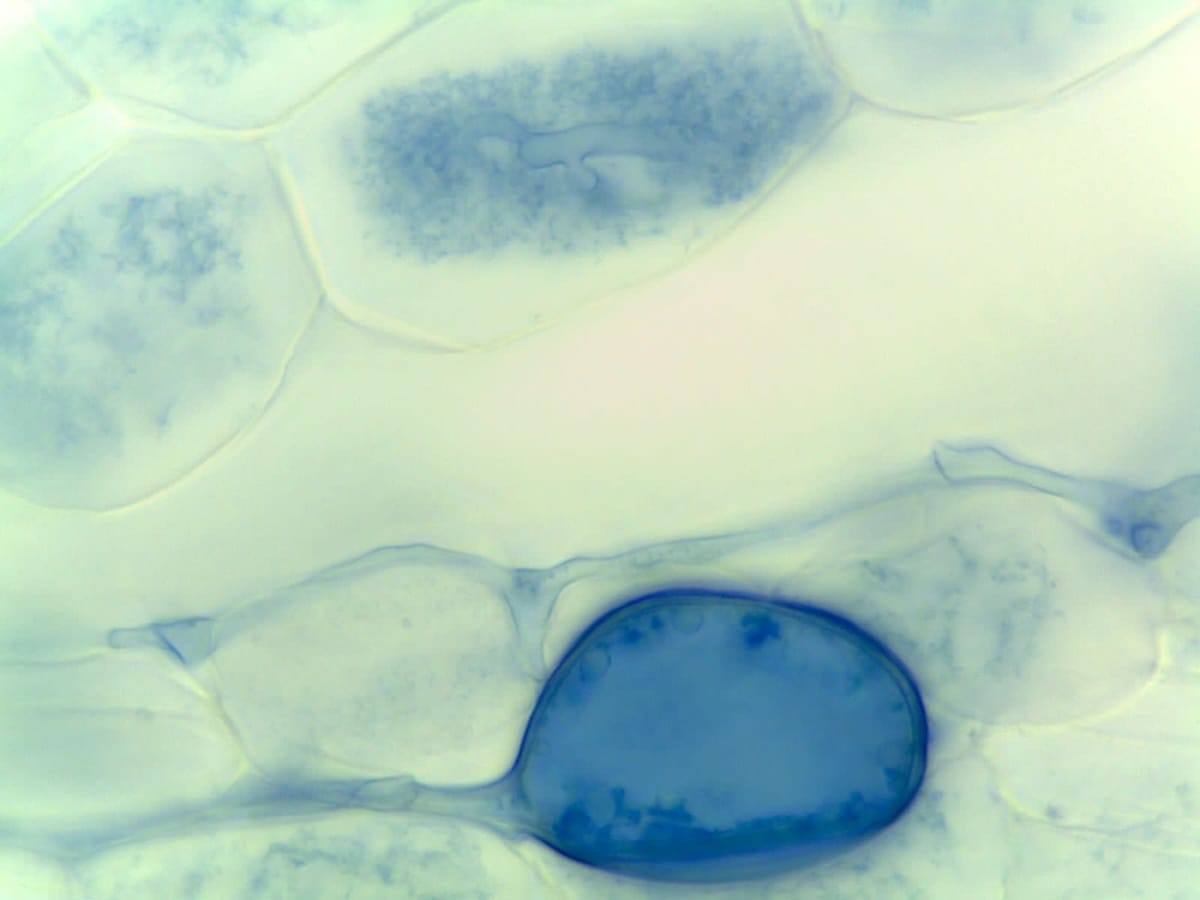

The second is when I get to look at the collected roots under the microscope. Each root is unique, even within the same plant species. And when I see the mycorrhizas, I feel a deep joy. As I observe, I begin to wonder: what are these fungi doing? Which species are behind these functions? What stories are hidden there? That moment of reflection and discovery is something I truly treasure.

Are any specific plants or species that have intrigued or inspired your research? If so, what are they and why?

Although my research has expanded beyond the sclerophyllous forest to include other plant species and others vegetation formations, it all began with some of the emblematic trees from that system. They deeply inspired me, and I want to take this opportunity to thank them: Peumus boldus, Lithrea caustica, Quillaja saponaria, Cryptocarya alba, Luma apiculata, Kageneckia oblonga, and Escallonia pulverulenta, for opening the door to a fascinating and little-explored world: the mycorrhizas associated with them. My goal has been not only to conserve and restore these plants and others linked to the sclerophyllous forest, but also to help preserve their ecological functions, to protect the integrity of the whole system, not just its species list.

Could you share an experience or anecdote from your work that has marked your career and reaffirmed your fascination with plants?

One of the most meaningful experiences in my career has been doing science outreach and interdisciplinary research at the intersection of science and art. Through this, I’ve seen how the work we do in the research group I lead can have a real impact on the communities connected to the ecosystems we study. Using diverse forms of communication, like art, helps bridge the gap between scientists and non-scientists. It places us on more equal ground, where we can share different ways of knowing, and it reminds us that what we’re researching has meaning not only for us as scientists, but also for the broader society.

What advice would you give young scientists considering a career in plant biology?

I believe this advice applies to any field of research: to pursue a career in science, there has to be a mix of passion and a clear sense of why your research matters. When both are present, deep interest and justified relevance, you’ll have the conviction to keep going and not give up. The path of research brings many satisfactions, but it also comes with challenges. In those tougher moments, that inner conviction becomes your fuel, it’s what keeps your fire going and lights the way forward.

What do people usually get wrong about plants?

More than wrong, what many people don’t realize is that plants, including their roots, host a complex microbiome full of bacteria and fungi that are absolutely vital for their survival and functioning. If we had a super-powerful magnifying glass and took a closer look, we’d see that plants are never truly alone. Mycorrhizas are formed by fungi living in closely relation with plants roots, creating fascinating structures that, under certain environmental conditions, help plants absorb nutrients better, support them against various stresses, boost the diversity of plant communities, facilitate nutrient cycling in ecosystems, and so much more. It’s a whole hidden world waiting to be discovered and admired!

Carlos A. Ordóñez-Parra

Carlos (he/him) is a Colombian seed ecologist currently doing his PhD at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Belo Horizonte, Brazil) and working as a Science Editor at Botany One and a Communications Officer at the International Society for Seed Science. You can follow him on BlueSky at @caordonezparra.