Plants are incredibly diverse, and so are botanists! In its mission to spread fascinating stories about the plant world, Botany One also introduces you to the scientists behind these great stories.

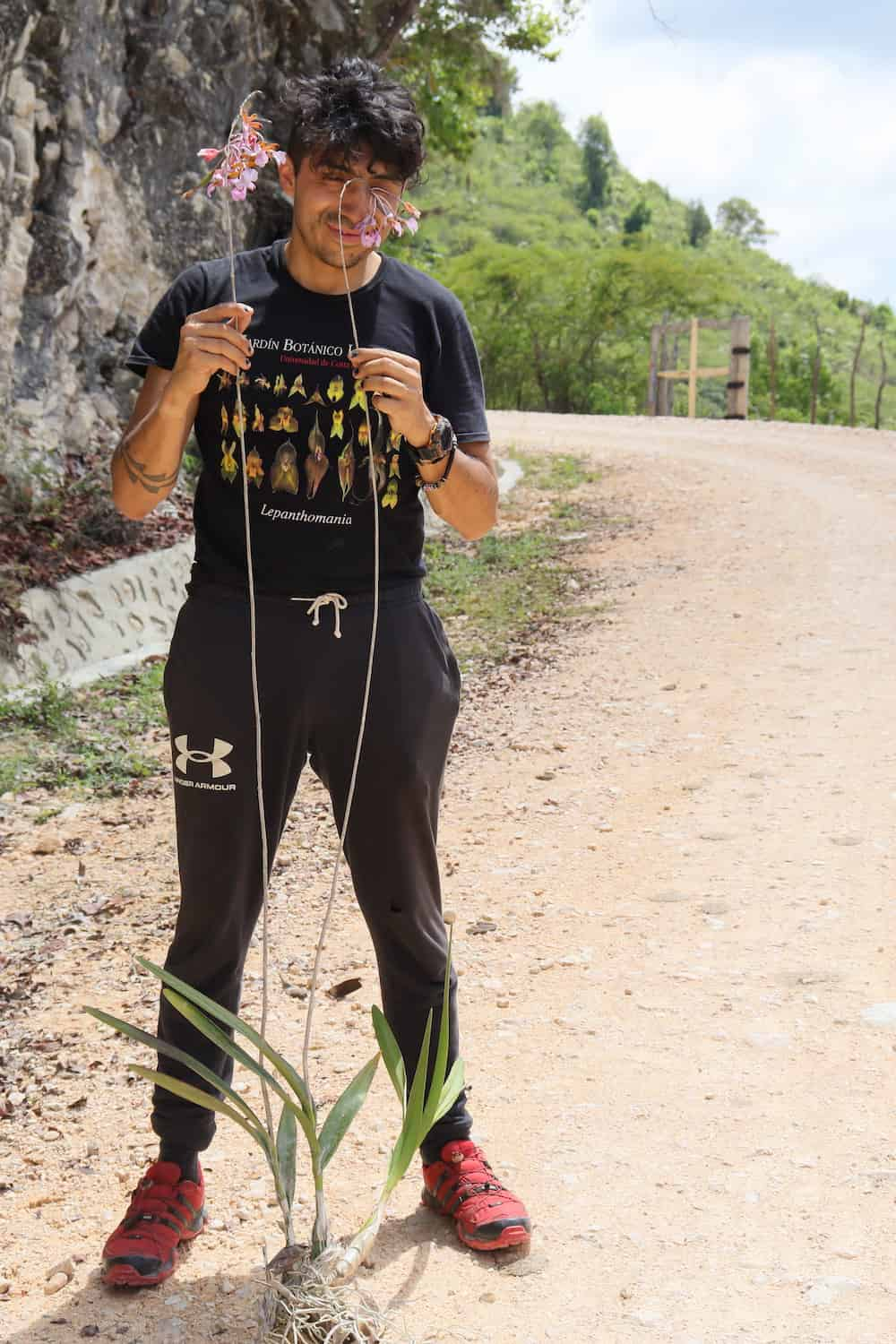

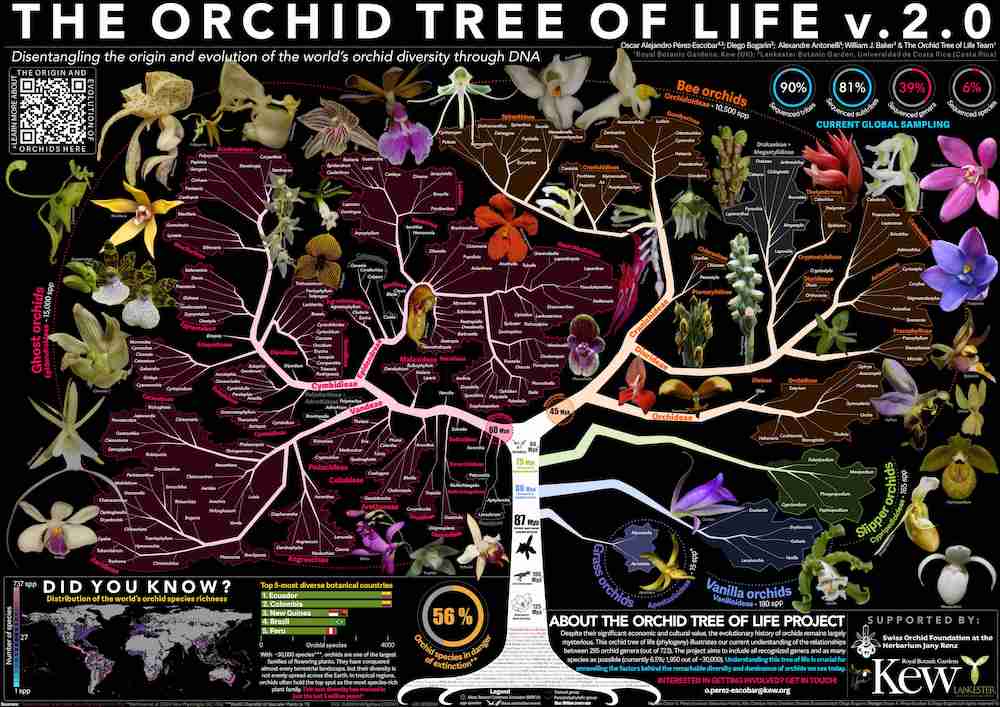

Today, we have Dr Oscar A. Pérez-Escobar, a Colombian botanist and evolutionary biologist, deeply engaged in uncovering the evolutionary forces that shape plant diversity. Currently, he serves as the Sainsbury Orchid Research Leader at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and a member of the board of trustees of the Swiss Orchid Foundation. His research primarily focuses on orchids, the most diverse family of flowering plants. As part of this, he leads the Orchid Tree of Life Project, an ambitious initiative to construct the most densely sampled phylogeny of orchids by including all currently accepted genera and all sequenced orchid species available in public repositories. This phylogeny will shed light on key questions such as why orchids are so diverse, when this extraordinary diversity emerged, and how orchids attained their global distribution. In addition to orchids, Pérez-Escobar has a deep interest in the evolutionary history of cultivated plants, including the sacred coca tree (widely misunderstood due to its association with cocaine), as well as crops like watermelon and date palms. Alongside his colleagues, he investigates these crops by analysing DNA from historical specimens and ancient plant remains, some thousands of years old. You can learn more about his research at his website and his Instagram.

What made you become interested in plants?

My fascination with plants began when I was 16 years old, during my second semester studying agronomy engineering. Part of our coursework involved field expeditions to a nature reserve near Cali, on the eastern slope of the Western Andes. It didn’t take long for me to fall in love with the cloud forests and their incredible diversity. But what truly changed things for me was meeting Gamaliel Rios, a campesino responsible for maintaining the nature reserve’s facilities. Despite lacking formal education, Gamaliel had developed an impressive expertise in orchid identification. His passion was contagious, and he knew more about orchids than many of my professors at the time. It was during one of those trips that I first wondered: “Just how many orchids are there?” That question has stayed with me ever since and continues to guide my work today.

What motivated you to pursue your current area of research?

Two key motivations drive my research. First, the sheer amount we still don’t know about the biodiversity around us—especially in regions like Colombia, one of the most biodiverse countries on Earth. Despite this richness, Colombia remains a ‘darkspot’ in biodiversity research, with countless species still waiting to be described. This paradox—living in a biodiversity hotspot yet knowing so little about it—has always fascinated me.

The second driver is the urgent need to produce baseline knowledge that can inform conservation efforts. With biodiversity loss accelerating worldwide, understanding what species exist, where they are, and how they evolved is critical to protecting them. This sense of purpose motivates me to contribute to the growing body of knowledge that underpins global conservation efforts.

What is your favourite part of your work related to plants?

Fieldwork, without question. There’s something incredibly special about stepping into a plant’s natural environment and studying it where it thrives. In the case of orchids, despite centuries of research, there’s still so much we don’t know about their ecology, interactions with pollinators, and reproductive systems. These mysteries can only be unravelled through detailed field observations. Each expedition is like stepping into a living puzzle, and the thrill of discovery never fades.

Are any specific plants or species that have intrigued or inspired your research? If so, what are they and why?

Absolutely. Right now, the coca tree (Erythroxylum coca and E. novogranatense) fascinates me deeply. It’s a plant with a rich medicinal and spiritual history, yet it’s become globally misunderstood due to its association with cocaine. Coca has been safely used in traditional contexts for over 8,000 years—chewed or brewed in infusions—and is considered sacred by many indigenous cultures across the Andes and Amazon. Despite this, coca has been demonized to the point where all species in the genus Erythroxylum are banned internationally and its study stalled. But taxonomic, genomic and phytochemical research could hold the key to produce baseline knowledge to produce more sensible policies, and I find this tremendously inspiring.

Could you share an experience or anecdote from your work that has marked your career and reaffirmed your fascination with plants?

About three years ago, while doing fieldwork with some colleagues from the Botanic Garden of Bogotá in an incredible piece of cloud forest between Valle del Cauca and Choco departments, we came across a remarkable discovery that our eyes could not believe: We observed flowers of two quite morphologically distinct species, Lepanthes licrophora and Lepanthes silverstonei, growing on the same plant. We then realised that what we found was a sexually dimorphic Lepanthes. This sexual system is extremely rare in orchids since 99.9% of orchid species produce bisexual flowers. Since the establishment of the genus Lepanthes in 1799, a group with more than 1200 species distributed in the American Tropics, until present, we thought that they were always bisexual. What is most remarkable about the discovery of sexual dimorphism in Lepanthes is that it is a new report in the last 150 years, after Darwin himself discovered and reported this sexual system for the orchid genera Catasetum, Mormodes and Cycnoches in his 1786’ book! This taught me that there is still so much we do not know about our natural world and the natural history of its diversity, even after centuries of studying it, which I think is encouraging and reaffirming.

What advice would you give young scientists considering a career in plant biology?

Follow your curiosity, and don’t be discouraged by challenges along the way. Careers in plant biology—and science in general—require patience and persistence, but they’re incredibly rewarding. With biodiversity loss accelerating and climate change reshaping ecosystems, plant science will only become more vital in the years to come. If you’re drawn to botany, embrace fieldwork as early as you can. Observing plants in their natural habitats will teach you things no textbook can. Finally, seek out mentors and build connections—botany is a collaborative science, and the insights and support from others can make a huge difference.

What do people usually get wrong about plants?

One major misconception is that epiphytic orchids are parasites simply because they grow on other plants. In reality, they aren’t harming their hosts; they simply use trees as a platform to access sunlight and moisture.

Carlos A. Ordóñez-Parra

Carlos (he/him) is a Colombian seed ecologist currently doing his PhD at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Belo Horizonte, Brazil) and working as a Science Editor at Botany One and a Communications Officer at the International Society for Seed Science. You can follow him on Bluesky at @caordonezparra.