Biodiversity is often described as the “web of life,” and for good reason, it underpins everything from clean water and breathable air to the food on our plates. Yet, while scientists can measure biodiversity by counting how many species are in a given place or describing how abundant or rare they are, there’s another crucial dimension: how people perceive it. This matters because being in biodiverse places doesn’t just benefit wildlife; it can also boost people’s mental health, lower stress, and even encourage physical activity.

However, there’s a twist. We are not only facing a crisis of species loss, but also an “extinction of experience.” With more people living in big cities and spending less time in nature, opportunities to notice biodiversity are increasingly shrinking. Understanding what people actually perceive when they step into nature could help bridge this gap. If we know which aspects of biodiversity people notice most, whether it’s the density of trees, the brightness of leaves, or the number of birds singing, then we can design green spaces that support both wildlife and human well-being.

To help answer these questions, a recent study led by Kevin Rozario and Taylor Shaw investigated how our senses of sight and sound shape our perception of biodiversity, and whether those perceptions match up with what ecologists measure.

The team ran two simple experiments, where researchers presented volunteers with either photographs of European temperate forests or ten-second audio recordings from the same woods, and asked them to group them any way they liked—by “dense vs. open,” “bright vs. shady,” “calm vs. lively birdsong”. Then, they asked the same volunteers to sort the images or clips into “low,” “medium,” or “high” biodiversity

Meanwhile, the researchers estimated actual diversity for every photo and recording. For images, they counted how many tree species were featured in the photographs and assessed the forest structure with expert ratings of variation in canopy, understorey structure, and the abundance of understorey plants. For audio, actual diversity was simply the number of distinct bird species vocalising in each clip.

The study showed that people were better at noticing biodiversity than some earlier studies had suggested. When participants compared forests directly, they often picked up on differences in species richness and forest structure. When asked to sort forests by sight, people relied most on cues like vegetation density, light levels, and colour, while sound sorts were driven by birdsong qualities, volume, and even the sense of time or season that the recordings evoked.

Crucially, people’s impressions were not random guesses. Perceived diversity strongly matched actual biodiversity, whether measured by tree species and forest structure in photos, or by the number of bird species in recordings. In fact, the correlation was strikingly high, especially for sound. This suggests that humans are better biodiversity detectors than we might assume.

Interestingly, the team also tested whether simple indices could act as shortcuts for measuring both “real” and “perceived” diversity. They found that a Greenness Index, a measurement of how green an image is, reflected both the actual number of species and the diversity people thought they were seeing. Moreover, they found a strong correlation between all their acoustic indices—capturing how complex, frequent, continuous, and wide-ranging the birdsong was—and both the perceived and actual biodiversity in each forest.

In the end, this study highlights something both simple and profound: when we step into a forest, our senses give us a fairly accurate picture of its biodiversity, meaning that our everyday sensory impressions do reflect real ecological complexity. As a result, city planners and conservationists could use simple visual and acoustic indices as cost-effective tools to gauge biodiversity, while also aligning with how people actually experience nature. By showing that people’s impressions align with scientific measures, the research strengthens the case for conserving and restoring diverse forests rich in tree species and birdlife. Such forests sustain ecosystems while also making us feel healthier and more connected. Looking ahead, expanding this kind of work across all our senses could help design green spaces that benefit both people and nature, reminding us that protecting biodiversity is as much about human experience as ecological survival.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Rozario, K., Shaw, T., Marselle, M., Oh, R. R. Y., Schröger, E., Giraldo Botero, M., … & Bonn, A. (2024). Perceived biodiversity: Is what we measure also what we see and hear?. People and Nature. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.70087

Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz

Erika is a Colombian biologist and ecologist passionate about tropical forests, primates, and science communication. She holds a Master’s degree in Ecology and Wildlife Conservation from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and has been part of Ciencia Tropical since 2020—a science communication group that aims to connect people with biodiversity and raise environmental awareness. You can follow her and her team on Instagram at @cienciatropical.

Spanish and Portuguese translation by Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz.

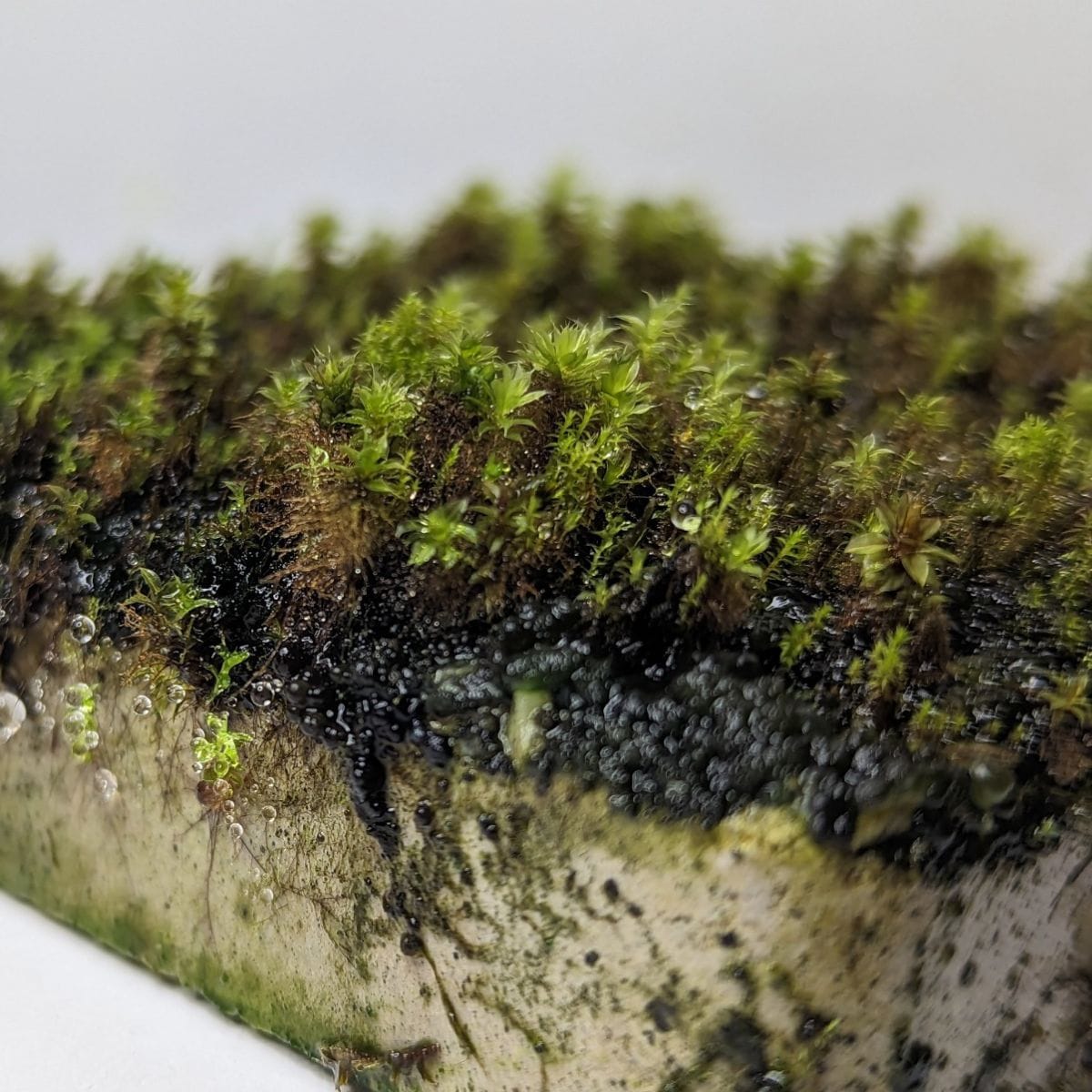

Cover picture by Guilhem Vellut (Wikimedia Commons).