Understanding how plants reproduce is critical to understanding ecosystem dynamics, and pollination plays a vital role in these processes. Most flowering plants, or angiosperms, rely on animals for pollination, while about 10% depend on the wind to spread their pollen.

But here is where things get even more intriguing: some plants use both animals and the wind to reproduce, a strategy called ambophily. Despite how fascinating this sounds, ambophily has been largely overlooked in pollination research, with less than 1% of studies evaluating ambophilous species. This lack of studies has left scientists with a dilemma: is ambophily truly rare, or we haven’t been paying enough attention to it?

Ambophily might actually be a clever evolutionary strategy that helps plants thrive in challenging environments, especially where animal pollinators are scarce. For example, open habitats like tropical highland grasslands create the perfect conditions for both animal and wind pollination, which could explain why we find more ambophilous species there than previously thought. However, past research in these ecosystems has often focused on primarily wind-pollinated species, leaving a big part of the plant community unexplored.

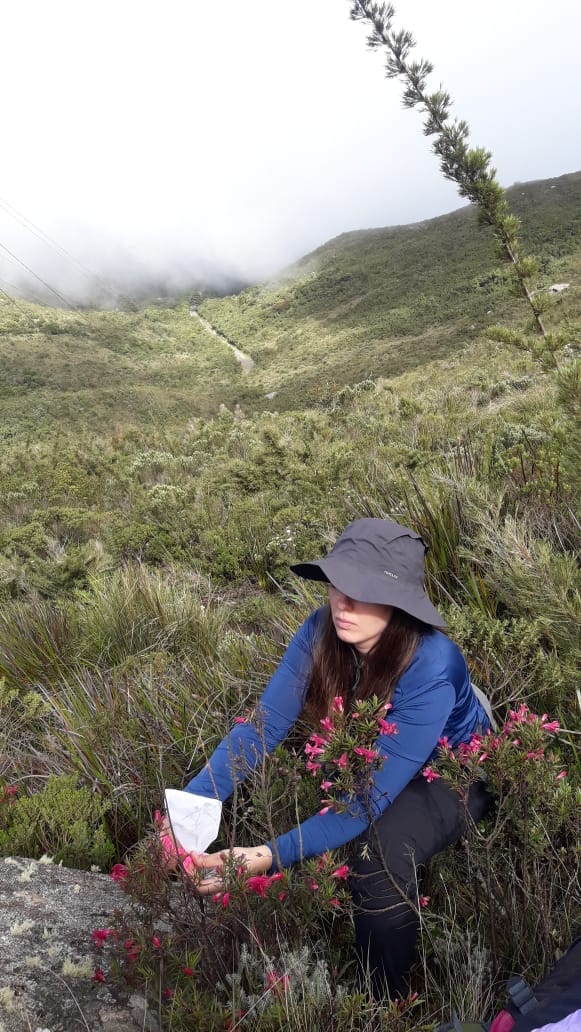

With this gap in mind, Amanda Pacheco and her team from the Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro examined 63 plant species in the campos de altitude at Itatiaia National Park, an incredible location in southeastern Brazil at about 2,300 meters above sea level. The researchers wanted to evaluate how both wind and animal pollination contributed to seed production in these plants. To do this, they conducted controlled pollination experiments, where some flowers were bagged to either exclude or allow wind or animal pollination. By the end of their experiments, they considered a species to be ambophilous if both animal and wind-pollinated flowers produced viable seeds.

The researchers found that 7 of the 63 plant species (11%) were pollinated by both animals and wind, meaning they are ambophilous. While this number might sound rather low, it increases the number of known ambophilous species by around 5% and all these records come from a single plant community.

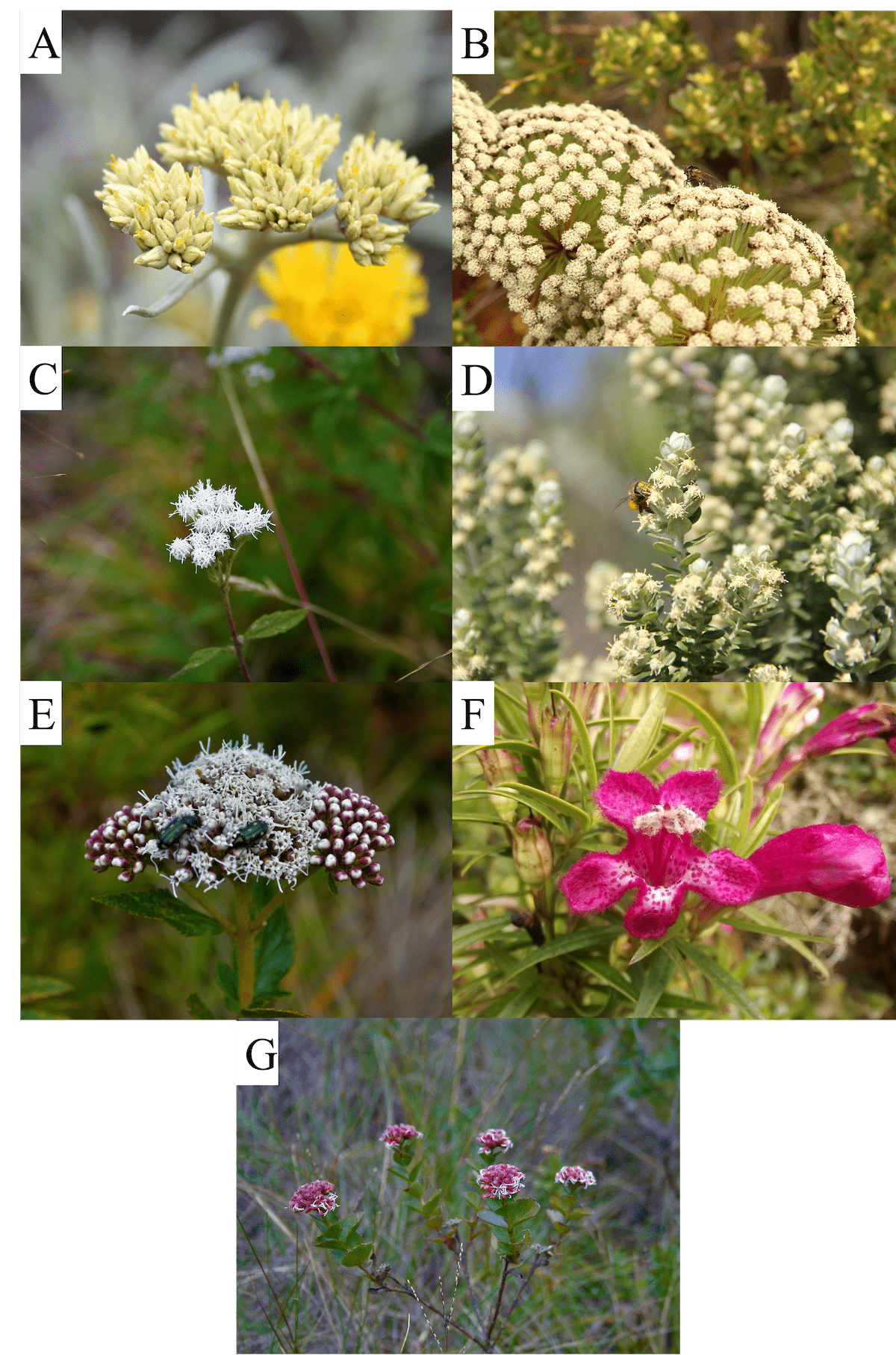

The high frequency of ambophily in the campo de altitude can be explained by a combination of environmental factors, including adequate wind speeds, open vegetation, and low animal visitation rates. Moreover, most ambophilous species in this ecosystem had small and pale flowers that can be pollinated by many small insects, such as beetles, flies and wasps. The flower morphology doesn’t prevent wind from transporting pollen, suggesting that wind could act as a complementary source of pollination. One could say that this dual strategy allows plants to embrace the best of both worlds: wind ensures pollination even when animals are scarce, while insects provide targeted pollen delivery.

The authors also highlight that ambophily may be more common than previously thought, mainly because wind’s contribution to pollination is rarely addressed in plant families that are typically animal-pollinated. Still, Esterhazya eitenorum, one of the ambophilous species described in this study, has large tubular flowers that are pollinated by hummingbirds and large bees. Thus, they call attention to a more comprehensive evaluation of different pollination vectors regardless of flower morphology.

These findings underscore the importance of thorough pollination studies in plant communities. Particularly, the study by Pacheco and her team opens the door to exploring how ambophily shapes plant survival and diversity in other ecosystems, offering exciting opportunities for future research on this fascinating yet understudied pollination system.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Pacheco, A., Bergamo, P. J., & Freitas, L. (2024). High frequency of ambophily in a Brazilian campos de altitude. Annals of Botany, mcae176. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcae176

Victor H. D. Silva is a biologist passionate about the processes that shape interactions between plants and pollinators. He is currently focused on understanding how plant-pollinator interactions are influenced by urbanisation and how to make urban green areas more pollinator-friendly. For more information, follow him on ResearchGate as Victor H. D. Silva.