As jewelflowers spread into California from the desert Southwest over the past couple of million years, they settled in places that felt like home, according to a new study by Bontager and colleagues. The work, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that the ability of plants and animals to adapt to changing climates might be more limited than it appears. It seems that what looks like climate adaptation might actually be niche construction, so that plants create familiar conditions instead of evolving to tolerate an expanded niche. This challenges the assumption that that species occupying different geographic regions have evolved different climate tolerances.

“I was honestly surprised,” said Sharon Strauss, Distinguished Professor emeritus in the Department of Evolution and Ecology and corresponding author on the paper. “They haven’t evolved as much as you would think.” The study also shows the important role that herbaria — collections of pressed and dried plants — can play in ecological research.

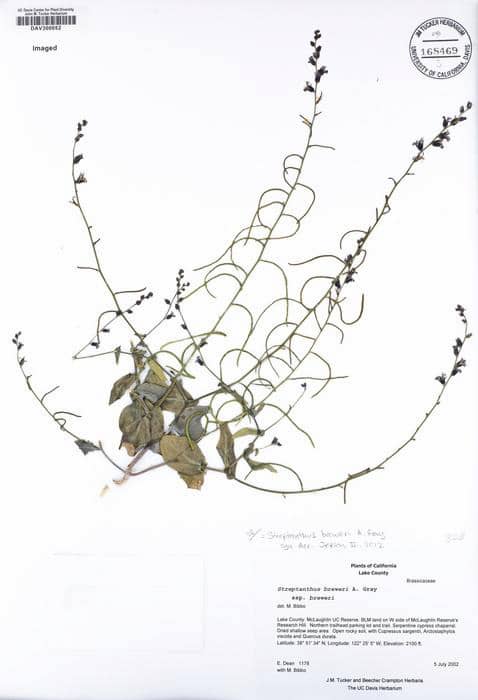

Strauss, postdoctoral scholar Megan Bontrager and colleagues used about 2,000 specimens of 14 species of jewelflowers from the Consortium of California Herbaria, an online resource that draws on multiple plant collections, including UC Davis’ own herbarium. Most jewelflowers are annual plants that germinate with the first significant rainfall of the season. By reconstructing local climate conditions for each specimen, the researchers could therefore estimate when the plant germinated from seed, and how long it had been growing before being collected.

Based on the average climate over a year, some jewelflower species live in areas much colder and wetter than others. But when the team looked at the local climate at the time the plants were growing above ground, a different picture emerged. The environments in which the growing plants spent their time were generally warmer and drier than surroundings.

“If you look at the annual climate, you would think that they have diverged a lot, but actually the species are good at tracking hotter, drier times and areas,” Strauss said. For example, the plants might favor sunnier, south-facing slopes. At the northern end of their range, jewelflowers are found in areas with drier soils.

The research shows how the “lived” climate can be different from the annual climate when plants take advantage of microclimates or refuges, or use strategies such as changing their timing of germination or flowering. This finding has implications for conservation planning.

If jewelflowers are finding local niches in environments, then species distribution models based on annual climate data may dramatically overestimate species’ climatic tolerances. Local populations may require very specific local circumstances, meaning that close development may drive them to extinction rather than leave them room to escape. In the case of jewelflowers, which have several endangered species, it suggests that conservation strategies should focus on protecting specific seasonal conditions and microrefugia.

For the jewelflowers, this conservatism may also explain why they can grow in serpentine soils, soils derived from weathered rock that are unwelcoming to most plants. This adaptation would be a response to remaining in the same climate niche. A paper by Qiao and colleagues recently argued that the inability of some plants to adapt may, surprisingly, be a driver of evolution. What appears to be a paradox, is due the to fact that the niche conservatism means that populations fragment and become isolated, leaving them to evolve in their own way, compared to their distant kin.

The authors point out that their methodology allows scientists to take a more sophisticated approach to climate. A seed is probably much more hardy than a seedling, so winter temperatures and average temperatures may be a lot less important than seasonal temperatures around germination. Herbaria, where the phenology and growth stage of plants is preserved, along with a date and location of collection, can provide the data needed for this closer look at climate. In their paper, the authors cite some examples.

For the annual plant Mollugo verticillata, species distribution models built from climate records of herbarium specimen collections by month and year were more accurate in predicting spatial occurrences than those using long-term average climate predictors. Seasonal models also better predicted occurrences of invasive mustard Capsella bursa-pastoris in the novel range than annual niche models.

This study underscores the importance of herbaria for understanding species responses to environmental change. Combining century-old speciemens with modern climate databases can reveal cryptic niche conservatism that could be masked by annual climate analyses. In the stores of herbaria like natural history collections that provide a temporal depth and understanding of species that cannot be gained from field studies alone.

READ THE ARTICLE

Bontrager, M., Worthy, S.J., Cacho, N.I., Leventhal, L., Maloof, J.N., Gremer, J.R., Schmitt, J. and Strauss, S.Y. (2025) “Herbarium specimens reveal a constrained seasonal climate niche despite diverged annual climates across a wildflower clade,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 122(28), p. e2503670122. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2503670122.

Original press release: Eurekalert.

Cover image: Streptanthus breweri CC-BY Chloe and Trevor Van Loon / iNaturalist. You can find Chloe Van Loon’s naturalist blog at https://chloevanloon.com/blog/.