The research by Panchen and colleagues used herbarium records of 97 species from the past 120 years. Digitisation of herbarium material allowed the team to examine 17,000 individual specimens, tagged with a date and place of collection to see how plants responded to climate.

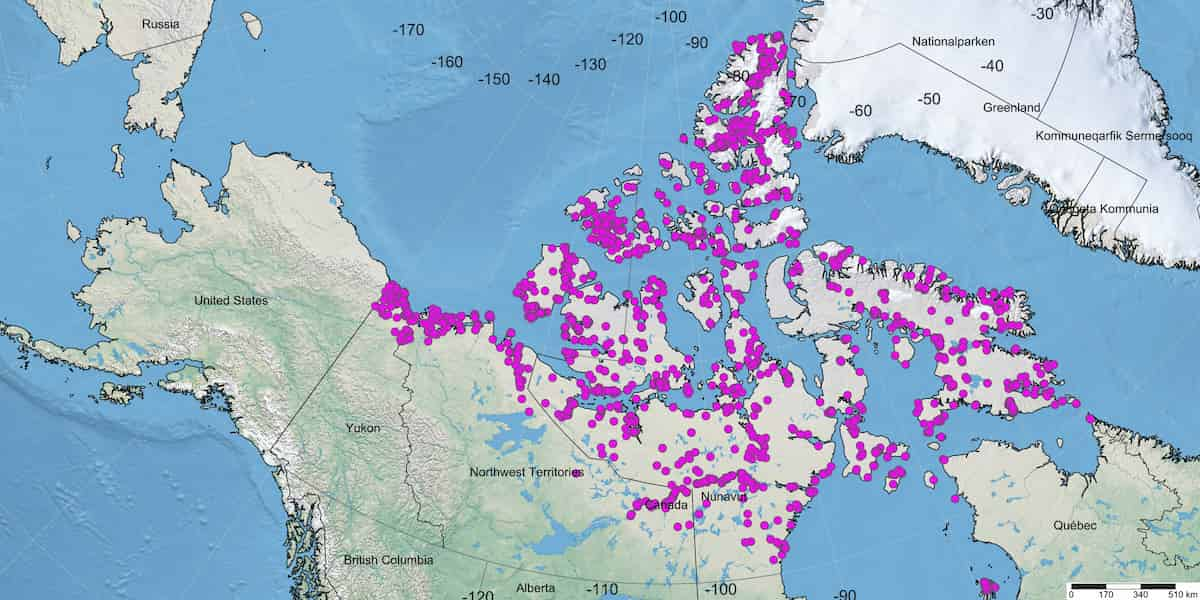

Tracking Arctic systems is difficult, but important as the region is warming 3× faster than the global average. Would more heat allow plants to grow for longer? To see if this was happening, the team examined the digitised records of herbaria to see what the plants actually did. The botanists examined the specimens, using high-resolution images. Each specimen was scored for flowering stage. Using herbaria meant the team had effective access to all the Canadian tundra, and comparisons over many decades for plants. The results are worrying.

Warmer temperatures mean plants flower earlier. The plants flowering early in the season advanced by around a day. BUT warming is greatest later in the season. This causes plants flowering later in the season to advance flowering by a lot more, so overall the flowering season shortens.

The changes in plants have effects on insects. While nectar is available sooner, the much earlier flowering for late season plants means flowering is over a lot sooner. A shorter flowering season means less time for insects to gather nectar and pollen.

The shorter season compresses competition for insect pollinators, which will affect plant reproduction. At the other end of the food web, the things that eat insects, like birds and rodents, will also have a reduced feeding period, as the effects of changes cascade through the ecosystem. Panchen et al write: “Convergence of flowering times of later- and earlier-flowering species could alter the competitive dynamics in tundra plant communities, possibly leading to changes in plant community composition and species abundance.”

This also suggests that some plants may become conservation priorities. Plants that are less able to adjust their flowering times may find that warmer temperatures put them out of sync with insect partners, or else vulnerable to other problems while trying to grow seeds in the rising heat. The problem is not simply that the changes are happening quickly, the change is also accelerating, so this paper is a warning that close monitoring is vital. Changes in the north can reach a long way south.

READ THE ARTICLE

Panchen, Z.A., et al. (2025) “Digitised herbarium specimen data reveal a climate change-related trend to an earlier, shorter Canadian Arctic flowering season, and phylogenetic signal in Arctic flowering times,” New Phytologist. Available at: https://doi.org/pwnc (FREE)

Cross-posted to Bluesky & Mastodon.

Cover image. Saxifraga oppositifolia in Switzerland by cortina/ Naturalist. CC-BY.