The First World War (1914–1918) was a defining moment in modern history, remembered for its devastation and upheaval. When we think about it, images of battlefields and destruction naturally come to mind. But a recent study published in Plants, People, Planet shows us that even in such turbulent times, botany found ways to thrive.

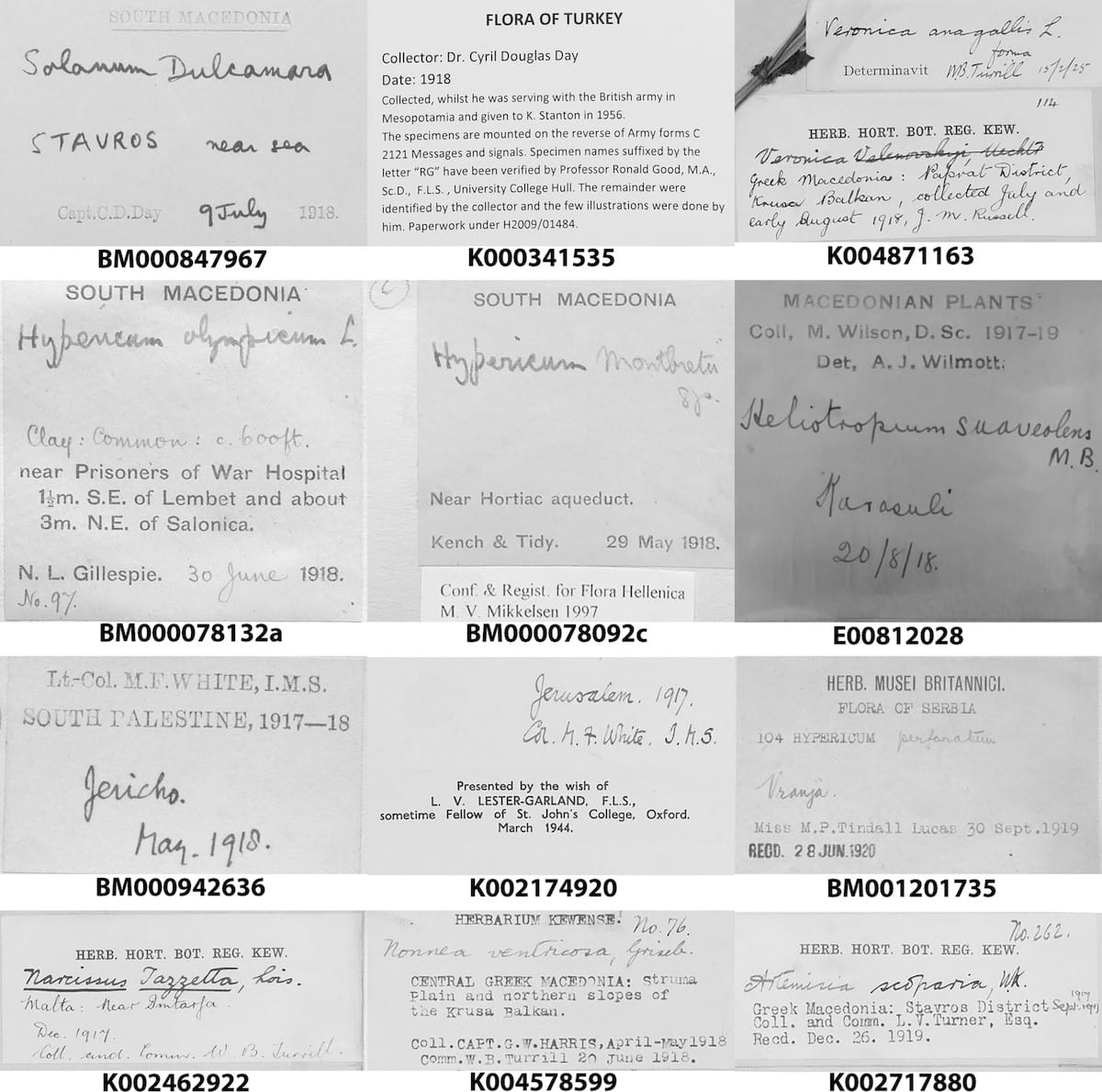

Christopher Kreuzer and James A. Wearn, both researchers at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, examined digitised herbarium specimens from their home institution, as well as those held by the Natural History Museum in London and the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. These institutions have made significant efforts to digitise their impressive plant collections, photographing pressed plant specimens and uploading key information such as where and when each plant was collected, who collected it, and sometimes even why. As a result, researchers have uncovered patterns that were long hidden in plain sight or buried in outdated catalogues.

Kreuzer and Wearn looked for specimens collected during the war years, filtering results by known collectors and war-related locations. Once promising leads appeared, they expanded their search to include lesser-known individuals, underexplored regions, and even collections made just after the war, in 1919 and beyond. But this work is about more than wartime history or cataloguing plants. By analysing these collections, Kreuzer and Wearn set out to uncover how botanical collecting persisted during the chaos of war. Their findings also carry modern relevance, as the researchers argue that these insights can inform how we record biodiversity today, especially in regions affected by conflict.

But online records only tell part of the story. To go deeper, the researchers examined the physical specimens themselves and their original handwritten labels, often revealing vital clues such as names, military ranks, or collection sites that weren’t captured digitally. They also turned to institutional archives and old accession books to trace how these plants made their journey from the battlefield to the herbarium shelf.

This botanical detective work revealed more than 4,600 previously unrecognised specimens gathered during the war by at least 30 overlooked collectors. By comparing digital records across institutions, the researchers corrected errors, reconnected fragmented collections, and brought to light forgotten campaigns, like a large-scale plant collection effort among troops on the Salonika Front. One such initiative was orchestrated by British botanist John Ramsbottom, who organised a plant collecting competition for soldiers. He observed in 1917 that “there is a great dearth of anything to interest the men,” and saw collecting as a way to engage bored and demoralised troops. The authors estimate that Ramsbottom’s competition alone may have produced up to 4,000 herbarium sheets. What’s surprising is not just how much plant collecting occurred during wartime, but how coordinated and scientifically valuable those efforts were.

Kreuzer and Wearn argue that war interrupted scientific routine, but it didn’t stop it. Instead, it reshaped how scientists work. Many of these collections entered institutional archives but were never fully catalogued or published, until now. And digitisation doesn’t just help scientists; it helps us understand the motivations of ordinary people who, even in wartime, turned to nature for meaning, distraction, and discovery.

In the UK, a 2022 survey found that less than a quarter of biological collections had any digital record, and only 2% were considered “research-ready.” That’s changing fast, thanks to projects at places like the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and the Natural History Museum in London, which are racing to make millions of specimens accessible online. This new accessibility allows researchers to spot patterns and connections that were previously invisible. While earlier studies focused on plant collecting during specific wars or countries, Kreuzer and Wearn’s study takes a broader approach: tracing wartime collections across institutions and decades. Their work contributes to the emerging field of polemobotany: the study of plants in the context of war, whether used for camouflage, medicine, food, or psychological comfort.

This research shows us that plant specimens gathered during the First World War aren’t just historical curiosities: they are living records of how science, society, and even individual psychology intersect in times of conflict. Thanks to digitisation, these once-forgotten collections are now re-emerging as vital sources of information. They reveal how botanical curiosity persisted through wartime chaos, how nature offered soldiers moments of peace, and how today’s scientists and historians can learn from what was once left unpublished. As we face modern conflicts and environmental crises, these rediscovered specimens offer a tangible link to the past and a reminder that documenting biodiversity, even under the most difficult circumstances, matters for the future of ecological restoration, scientific understanding, and the human spirit.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Kreuzer, C., & Wearn, J. A. (2025). How digitisation of herbaria reveals the botanical legacy of the First World War. Plants, People, Planet. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.70028

Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz

Erika is a Colombian biologist and ecologist passionate about tropical forests, primates, and science communication. She holds a Master’s degree in Ecology and Wildlife Conservation from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and has been part of Ciencia Tropical since 2020—a science communication group that aims to connect people with biodiversity and raise environmental awareness. You can follow her and her team on Instagram at @cienciatropical.

Spanish and Portuguese translation by Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz.