Plants produce nectar, a sugary drink that works like a universal snack bar for animals, from busy bees to ants on patrol. But not all nectar is equal. Just like soft drinks can vary in sweetness, flavour, and fizz, nectar differs in sugar type, concentration, and added ingredients, such as proteins or oils. These differences shape how animals choose where to feed, how they move between flowers, and ultimately how plants reproduce and protect themselves.

This sweet liquid is produced in tiny organs called nectaries. They can be hidden inside flowers to attract pollinators, or they can appear elsewhere on the plant, where their role is more about defence. Since making nectar costs energy, plants have developed different strategies, adjusting not only how much to produce but also when and where to release it.

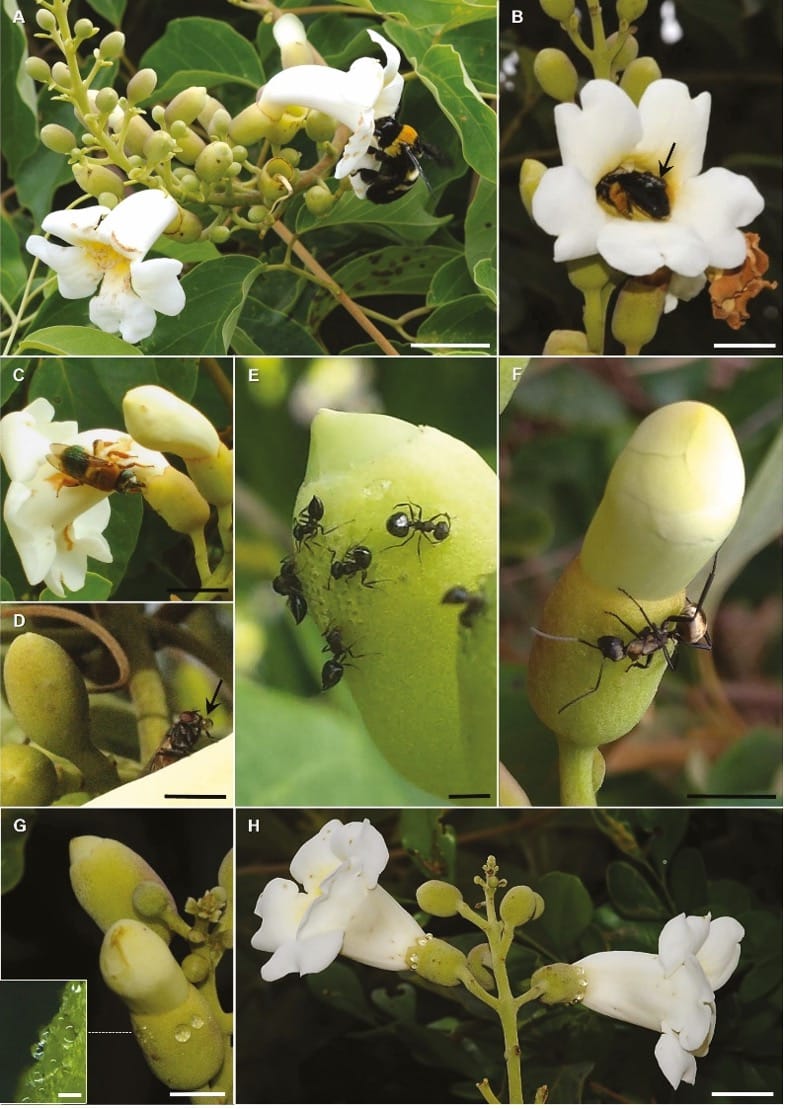

One fascinating case is Amphilophium mansoanum, a Brazilian liana from the Bignoniaceae family. Each of its flowers comes equipped with two very different kinds of nectaries: nuptial and extranuptial. The nuptial nectaries are like the main buffet inside the flower, serving pollinators such as bees. The extranuptial nectaries sit outside on the outermost part of the flower and function more like snack stands for ants, which in turn help to protect plants against herbivores.

Earlier studies had shown that these two nectary types produce distinct recipes: the nuptial nectaries offer a sucrose-rich mix with special amino acids, while the extranuptial nectaries keep things simpler with a hexose-based blend. What remained unclear was how the physical structure of these nectaries, their anatomy and inner workings, tie into what they produce and when.

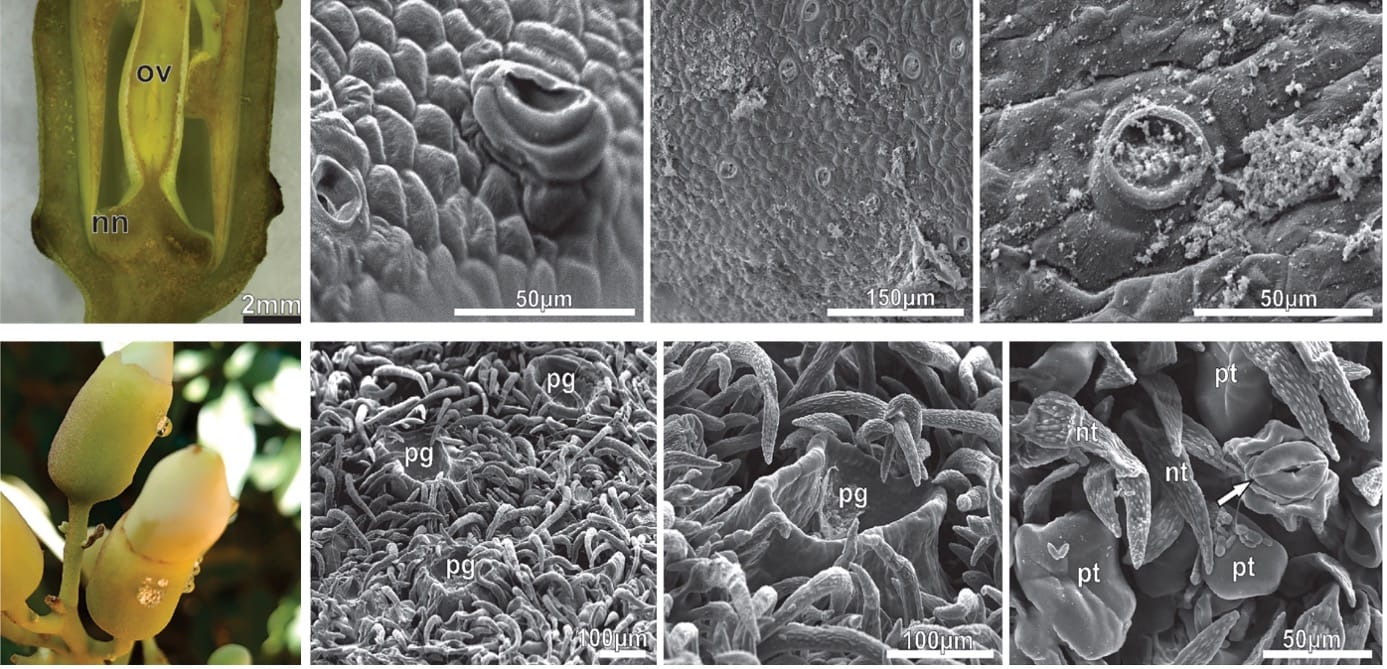

So, Hannelise Balduino and her team, instead of just looking at what is in the nectar, zoomed in on the nectar makers themselves. Using powerful microscopes capable of revealing whole tissues and tiny organelles inside cells, they tracked how these nectaries change across a flower’s lifetime. From tight green buds to fresh blooms and aging petals, the team followed the story of how structure shapes function, and how one plant manages two menus at the same time.

They found that nuptial and extranuptial nectaries have distinct structural characteristics, which lead to varied nectar features such as volume, concentration, and chemical composition. Located just below the ovary, nuptial nectaries form a little nectar disk surrounded by a chamber where nectar collects. Even before the flower opens, their cells are already busy, with tiny openings ready to release nectar. Inside, starch, oils, proteins, and other compounds are stored. Over the first two days of flowering, these cells transform dramatically: starch breaks down, vacuoles expand, and the cytoplasm becomes rich in proteins, oils, and phenolic compounds. This sudden burst produces a watery, sugar-rich treat at exactly the right moment to attract pollinators and ensure pollination.

In contrast, the extranuptial nectaries, situated on the calyx, secrete nectar slowly and steadily over several days. These glands have a three-part structure: a head where nectar is stored, a stalk connecting it to the base, and a foot embedded in the flower tissue. Even in young buds, the cells start producing nectar, gradually accumulating proteins, lipids, phenolics, and other compounds. Over several days, the secretion continues steadily. Their nectar is richer in lipids and aromatic compounds, which not only attract a wider variety of visitors but also protect it from drying out and from microbes, helping defend the plant.

In short, these two nectaries have very different “personalities.” One works quickly and intensely to attract the right pollinators at the right moment. The other provides a slow, steady supply of nectar to maintain broader interactions with many insects over time. Their cellular machinery is finely tuned for these roles, showing that nectaries are not just passive channels but dynamic systems.

These findings show that both types of nectaries are highly specialised. They store energy, produce enzymes and compounds, and manage the secretion process through intricate cellular machinery. By revealing how different nectaries within a single flower operate and attract distinct groups of visitors, scientists can gain a better understanding of the complex ecological interactions. In essence, the tiny differences in nectar production tell a big story about life, survival, and cooperation in nature.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Balduino, H., Tunes, P., Nepi, M., Guimarães, E., & Machado, S. R. (2025). Structure and ultrastructure of nuptial and extranuptial nectaries explain secretion changes throughout flower lifetime and allow for multiple ecological interactions. AoB PLANTS, plaf037. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plaf037.

Victor H. D. Silva

Victor is a biologist passionate about the processes that shape interactions between plants and pollinators. He is currently focused on understanding how urbanisation influences plant-pollinator interactions and how to make urban green areas more pollinator-friendly. For more information, follow him on ResearchGate as Victor H. D. Silva.

Portuguese translation by Victor H. D. Silva.