Ever witnessed a leafy roommate or neighbour fall to a swarm of hungry bugs? Now imagine living forever anchored to the ground in an insect-packed jungle. Plants don’t have it that easy, yet they aren’t passive victims at all. They’ve come up with a whole set of tricks to defend themselves over ages of evolution. Take chemicals, for example — from bitter substances that make plants unappetizing, to powerful toxins that can make herbivores sick or even kill them.

The thing is, most bugs still need their veggies, and many have evolved right back to overcome plant defences and keep munching on their favourite meals. Some even turn plant poisons to their own advantage. This silent struggle between plants and insect herbivores began some 400 million years ago and has likely been fuelling their evolution ever since. Recently, a new paper in Biology Letters shed new light on the intricacies of a long-known evolutionary contest between a group of tropical trees and their butterfly opponents.

Certain visionary plants have gone a step beyond chemical defences, establishing extraordinary alliances with other insects that help them fight off herbivores. For example, some species can emit gaseous SOS signals to attract wasps that feed on their uninvited leaf-chewers. Many others hire aggressive ants as private bodyguards, who get rid of freeloader bugs in exchange for food treats or shelter.

Among the most remarkable examples from Asian rainforests are Macaranga trees, a group of distant relatives of garden spurge and Christmas poinsettias. They include some species that lure a variety of ants by secreting sweet droplets of nectar on their leaves, or by growing tiny, nutrient-rich snack packs on their leaves and stems. Other Macaranga species go even further: they have hollow stems and other special structures where their loyal bug comrades can safely build their nests and raise their young.

Yet again, plant life isn’t that easy: herbivores won’t just give up on their food, and ants may not always be so loyal after all. A group of oakblue butterflies have learned to bypass the security system of Macaranga trees by bribing their guards with an irresistible reward. Their sneaky caterpillars have evolved specialized organs that secrete an enticing, nectar-like delicacy, which drives ants crazy. So, as long as the sugary bribe is supplied, the ant guards will forget their vow, and the host tree will get its leaves all nibbled. What on Earth could a plant do to fight back against such mischief?

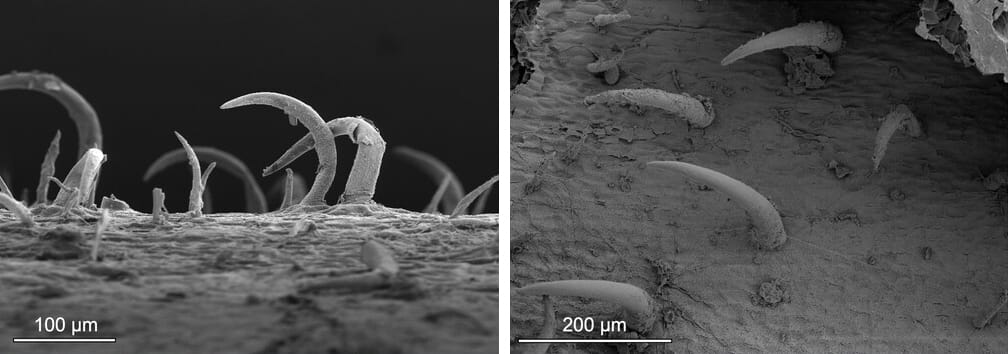

Out of the more than 300 described species of Macaranga, one stands out for having its body covered in tiny, hook-shaped hairs that give it a sandpaper feel to the human touch. Its name is Macaranga trachyphylla, a species endemic to the island of Borneo. Hairs, better called trichomes in botany, have long been recognized as one of the most widespread strategies of physical defence among plants. Yet, those of Macaranga trachyphylla hadn’t received much attention until recently. A group of researchers from Brunei and the UK, authors of the new study, discovered that such a unique feature of these trees serves as a powerful armor against shady caterpillars.

To find that out, the research team went through the rainforests of Brunei collecting oakblue caterpillars from various Macaranga species. They later tried putting them on Macaranga trachyphylla to see what happened, both in the field and in the lab, using collected branches. When placed on the stems or petioles, the little foliage-munchers met a fatal end. The moment they tried to walk, the plant’s sharp trichomes pierced their soft bodies and held them arrested, wholly preventing their movement and feeding. Indeed, the wounds eventually led most caterpillars to bleed out and die in a matter of minutes.