In an urban neighborhood of Stockholm surrounded by residential homes, supermarkets and parking lots, is an outlier: a forest garden. Upon entry into this greenspace, you will find a lush garden full of plants, encased by trees from the canopy above. This garden, like many others, was built by community members to increase access to edible plants in a sustainable way.

However, it turns out that the impact of these gardens on the community is not just food production, but socialization. A recent study published in Urban Forestry and Urban Greening conducted an inventory of urban forest gardens around Sweden and recorded the effects they had on the surrounding community, and found social and cultural aspects to be the most valued benefits of these urban gardens.

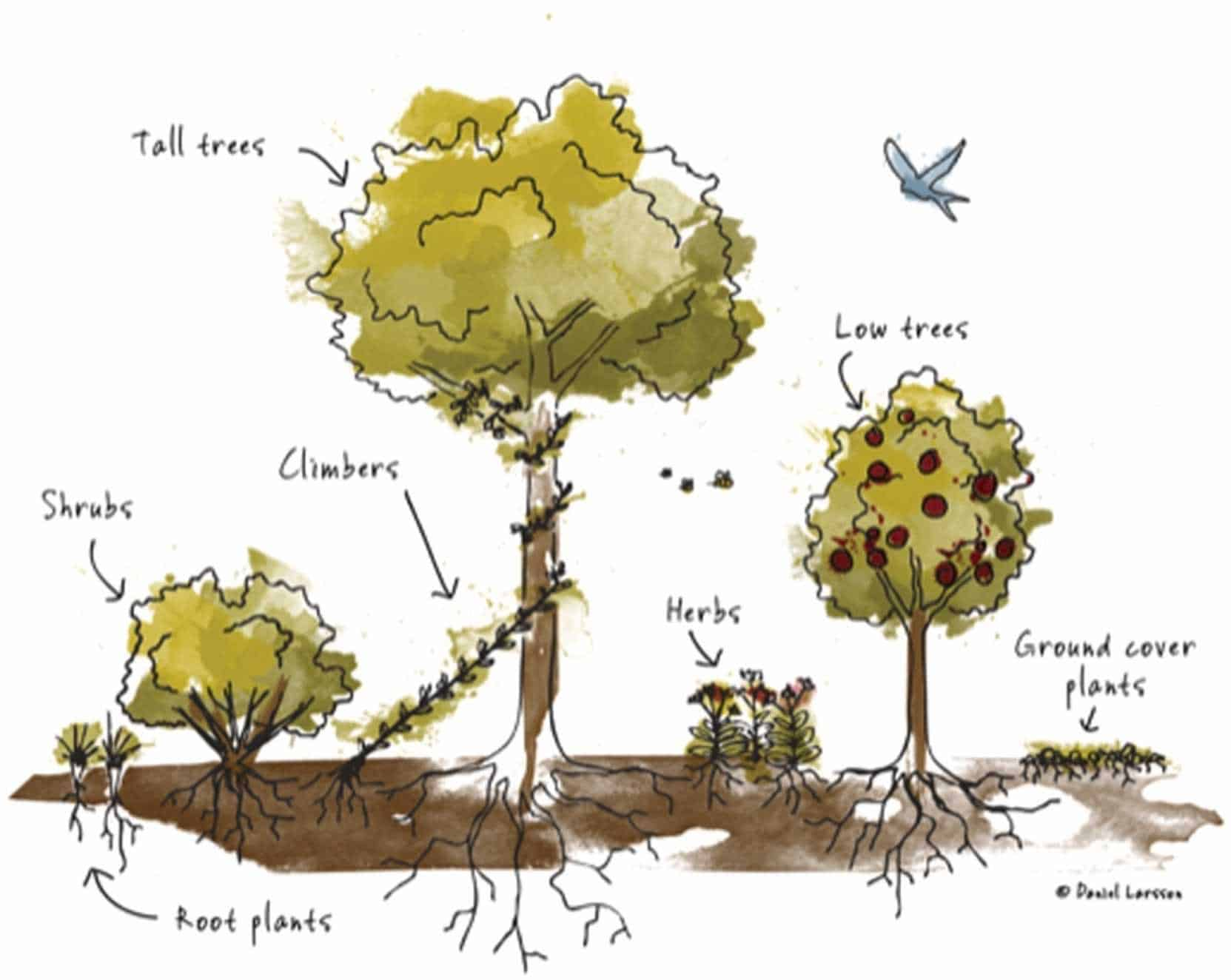

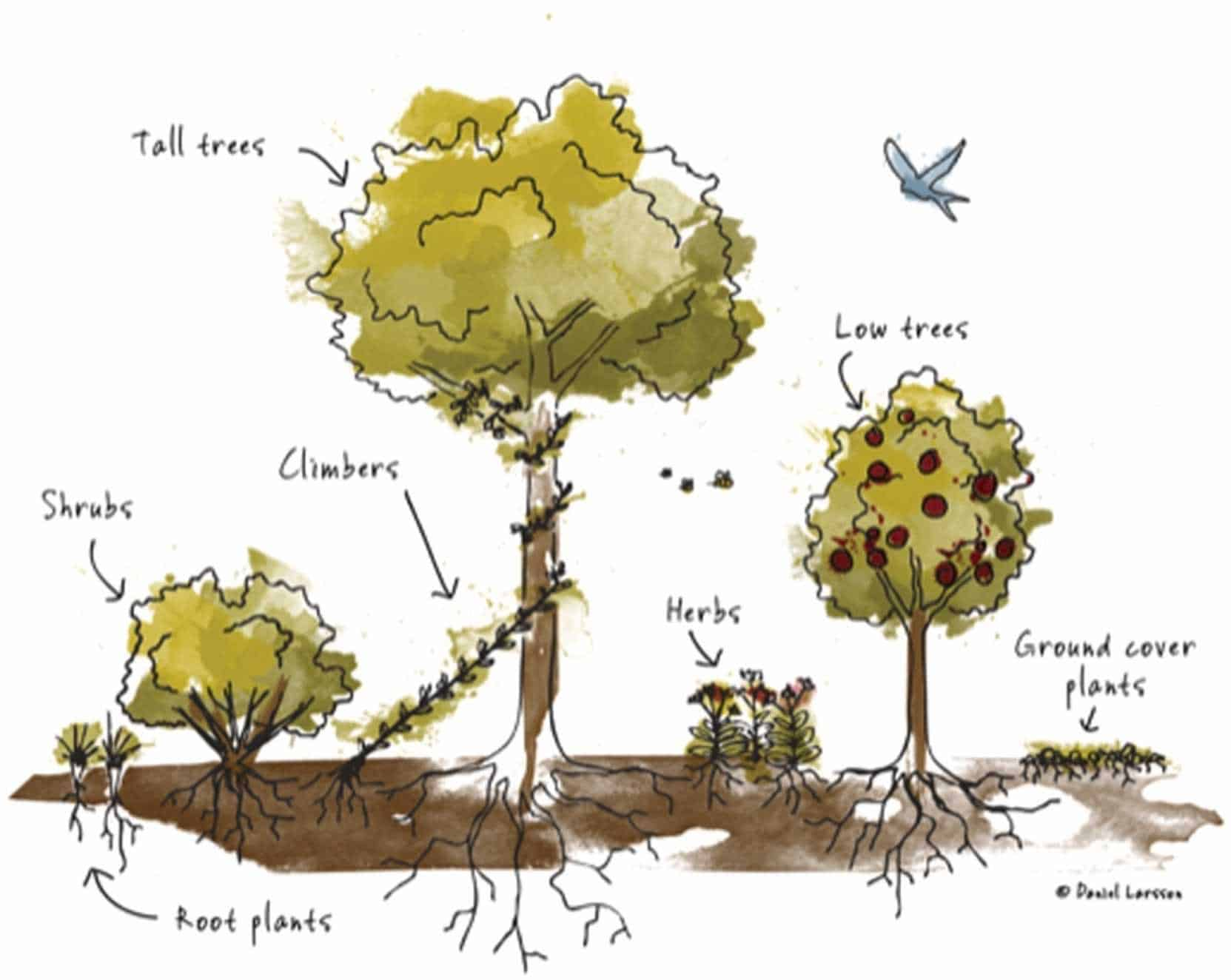

Forest gardens are unique from other garden types because they contain mainly perennial and woody perennial species, including apple trees, raspberries, gooseberries, and Caucasian spinach, which makes them a sustainable agroforestry system. They are also accessible to the public, either on public land or on private land that anyone can access.

“It is very much about social cohesion and learning,” says Christina Schaffer a researcher at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Stockholm University, “In cities, people don’t talk to each other or strangers, but if you have something like a community garden, people start to interact with their mates in the garden and other passersby get curious and want to know what they’re doing.”

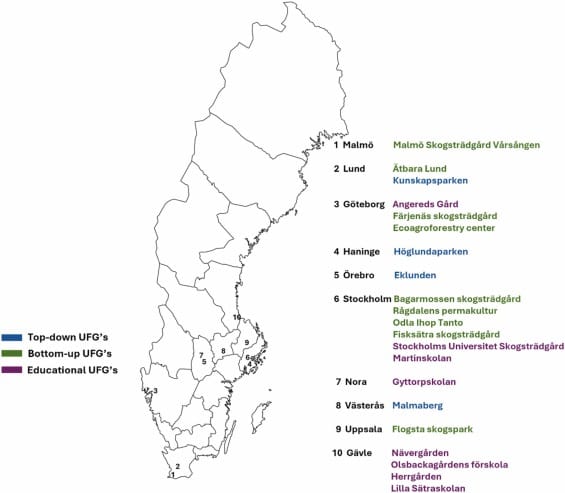

The team identified 30 different forest gardens across 10 cities in Sweden, all of which were established via one of three main mechanisms: a grassroots movement of community members, schools and educational groups, or municipal officials. The first forest gardens were established by grassroot movements in the late 2000s, which eventually inspired schools to start their own. More recently, municipalities have begun to fund and establish forest gardens for residents across their communities. As a result, garden prevalence has steadily grown in the last 15 years.

The early group of forest gardeners created what the researchers refer to as a ‘bottom-up’ system. With some seeking an escape from city life, community members created these gardens with the hopes of creating a more sustainable lifestyle and to produce healthy foods in their own neighborhood.

As they built these gardens, the participants established a network of local connections, hosted informal workshops for those looking to start their own gardens, and eventually wrote books on the topic. This ‘knowledge hub’ inspired and informed other groups to take action and build upon this knowledge and eventually laid the groundwork for ‘top-down’ garden systems built by municipalities.

Through interviews with those involved in these forest gardens, including government officials, teachers, and grassroot movement leaders, the researchers found that the courses and workshops that emerged from knowledge hubs directly influenced the creation of over 75% of the gardens included in their study.

“What was surprising was that this started as an underground movement that eventually inspired bureaucrats to bring these experiences into their offices and transform the governance of green spaces,” says Marco Focacci, a researcher at the University of Florence, Italy. “Now municipalities are using public funds to build forest gardens in public parks.”

While these forest gardens may have been established for sustainable food production, their impacts have spread well beyond their initial intent. Researchers found that interviewees valued the educational, cultural and aesthetics more than any other benefit of these gardens, including the cultivation of plants for food, energy and materials. Although the importance of the more specific values within these categories differed between the three groups (grassroots, educational, municipal), all groups expressed the importance of knowledge hubs in establishing a sense of community and influencing decision makers to support these gardens.

In the study, only four of the forest gardens were created with the top-down approach, but since then, four more have been established in Sweden.

“The hope is that [government] and city planners consider incorporating agroforestry as a type of green solution, especially in dense areas because of the many services they provide including food production and both social and cultural connections,” says Schaffer.

READ THE ARTICLE

Focacci, M., Schaffer, C., de Meo, I., Paletto, A. and Salbitano, F. (2025) “Exploration of the functions and potentials of urban forest gardens in Sweden,” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 112(128990), p. 128990. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2025.128990