In a frigid room lined with rows of floor to ceiling cabinets Kevin Faccenda, Invasive Species Program Manager at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawaii, sat at his desk sifting through around 100 pressed specimens of Amaranthus. Amaranthus, a grain that has been cultivated by civilizations for centuries, is found naturally in a variety of areas. However, over time this crop has evolved into an expansive number of species, some of which have escaped cultivation and become a problem for ecosystems, especially in Hawai’i.

As far as the museum’s records indicated, all the current Amaranthus collected in Hawai’i and housed in the museum’s herbarium were species introduced to the Hawaiian Islands. But all of that changed when Faccenda began examining each specimen and noticed something peculiar about one specimen collected from a remote area of Hawai’i Island in 2014.

“The specimen did not match any of the other Amaranthus reported in Hawai’i, nor did it match any North American or European species,” said Faccenda.

As he continued to examine the specimen and take measurements it became more obvious that this specimen was not like the others– in fact, it was a new species entirely. In a recent paper published in Novon, Faccenda and his team reported the finding of a new species, Amaranthus pakai.

In order to properly identify this mystery plant, Faccenda hit the books in search of records describing difference species of Amaranthus. In doing so, they were able to narrow down the species of the mystery plant to a close match, Amaranthus brownii, a now extinct plant known only from Nihoa, the southernmost island in Papahānaumokuākea. Although the match was not perfect, the similarities between the mystery plant and A. brownii indicated that this unidentified Amaranthus may be a species native to Hawai’i—and not an introduced one as previously thought.

The next step was an attempt to further categorize this plant within a current known species or describe it as an entirely new species. Typically, the best way to do this is to examine all the specimens in the plant’s related group, dating as far back as possible.

According to museum records, there were a handful of Amaranthus specimens collected from Hawai’i in the 1800s. These specimens were taken back to collections across the world however, while some wound up at the Bishop Museum’s herbarium, they were either lost while out on loan or destroyed in transit. Now, the only in-house specimens available were of those collected after the 1970s.

The lack of historical specimens available can make determining an identification difficult, as plant traits can vary within a species. The more specimens there are of a species to examine can increase the accuracy of estimating a plant’s evolutionary history. For example, if you were shown two pictures, one of a lion in the Sahara and one of a hairless house cat, there is a high chance you would not be consider them to be related. But if we put together pictures of all known cat species, connecting the dots of their relations becomes much clearer.

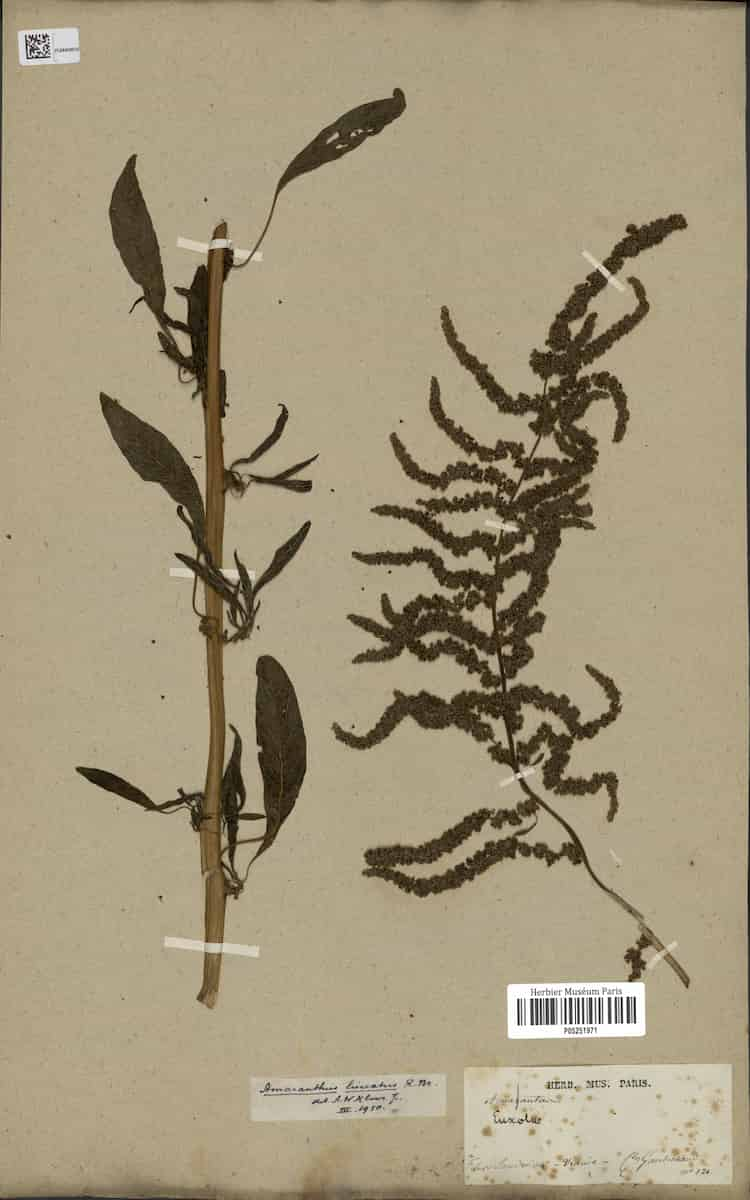

Despite the lack of physical records at the museum, Faccenda was able to search through digitized plant specimens that were collected in Hawai’i in the early 1800s that are located in other herbaria around the globe.

The digitization of natural history specimens has revolutionized the field of science for many researchers. Not only does digitizing specimen make them more accessible to people all over the world, it also serves as a digital history record. If a specimen is destroyed or damaged, an unfortunate reality for many natural history collections, the digital image can allow that lost specimen to be analyzed for centuries after it is lost.

While the new age of digitization brings promise, it requires a lot of hours and funding, something most institutions with natural history collections are lacking. With anywhere from 750,000 to several million specimens, natural history collections globally are struggling to sort through their collections and upload them online.

In the past, a researcher in Hawai’i would most likely never know about the existence of a specimen in the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, France. In a new age of technology and some strategic searching, he was able to locate a handful of matching specimens to his mystery plant housed in collections across the globe, in a matter of hours.

Interestingly, all the specimens he found were also misidentified as species that were non-native to Hawai’i.

This widespread misidentification did not come as much of a surprise to Faccenda, as there are not many people who are experts in identification of Hawaiian grasses, especially located so far outside of Hawai’i. He also noted that the location of these specimens would either make them unknown or largely inaccessible to botanists in Hawai’i until recently because of digitization.

“The ‘discovery’ of this species can be attributed to the many programs across the world that have digitized museum collections and published them online,” Faccenda said. “If anything, this finding only further highlights the importance of digitization and why we need to commit more funding towards it.”

In collaboration with a team from the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, France, Faccenda was able to verify that not only did the mystery specimen from 2014 match some of theirs, but there was a record from 1819 made by one of the specimen’s collectors with the Hawaiian name Amaranthus pakai. This is quite atypical, as newly found rare plants are often given a new name or named after the place in which they were found. It seems that over time the word pakai had been lost in translation and associated with non-native Amaranthus. With Faccenda’s find, they are able to prove its connection to an endemic Hawaiian plant, as non-natives were not found by that collector in 1819.

Amaranthus pakai has only been found on the Hawaiian Islands, which makes it endemic. Moreover, the most recent record of A. pakai alive in nature is from when it was collected in 2014, when at the time it was recorded that there were only about 30-40 plants in the area, making it a critically endangered species—an unfortunate, yet ongoing trend for native species across Hawai’i.

However, the collections made in the 1800s suggest that this species was actually widespread and most likely quite common. The dramatic loss in numbers could be the result of a variety of factors however, after finding a microscopic plant pathogen on the mystery specimen from 2014, Faccenda hypothesized that this pathogen may be the culprit.

While A. pakai has not been found alive in almost a decade, Faccenda still holds out hope that it’s out there in some remote area of the island. Since its new-found discovery there has been a call to all botanists on the Hawaiian Islands to report any potential sitings to the team.

“I have doubts it is still out there,” said Faccenda, “but if it is, hopefully someone can find it.”

READ THE ARTICLE

Faccenda, K., Bayón, N.D., Waselkov, K. and Hobdy†, R.W. (2025) “Amaranthus pakai (Amaranthaceae), a new Critically Endangered species from the Hawaiian Islands,” Novon : a journal for botanical nomenclature, 33, pp. 1–5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3417/2025953. (FREE)