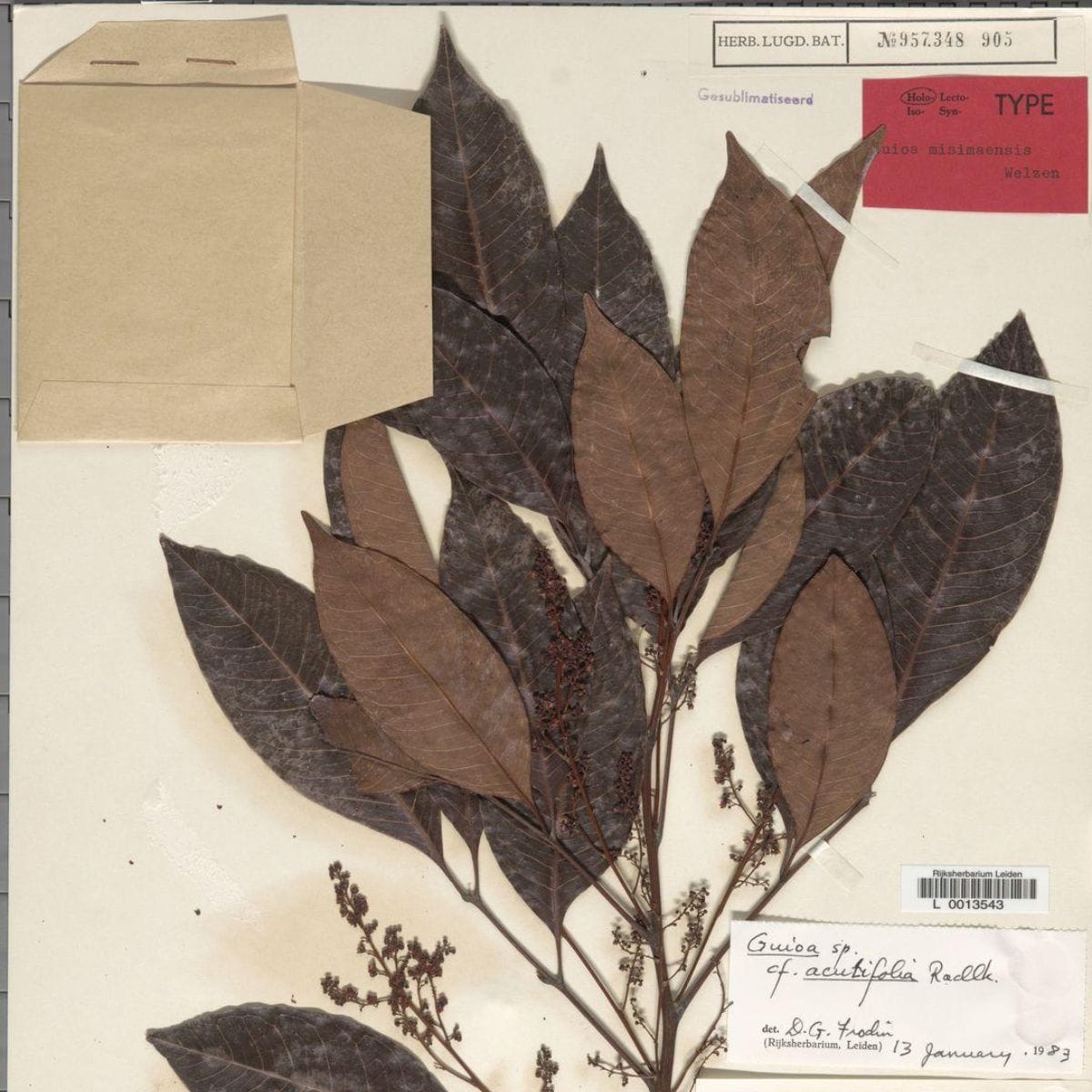

If you’ve ever visited a museum, you might have noticed how its most prized treasures are protected: kept behind glass, watched by guards, and carefully shielded from curious hands. In the botanical world, the closest equivalents are holotypes, the plant specimens chosen to define a new species. These single examples preserve the exact features that set one species apart from another, making them the definitive reference for scientists. Holotypes are the ultimate gold standard for identification, and when questions arise about a plant’s identity or how it is related to other species, botanists return to them. But where, exactly, are these precious specimens kept today?

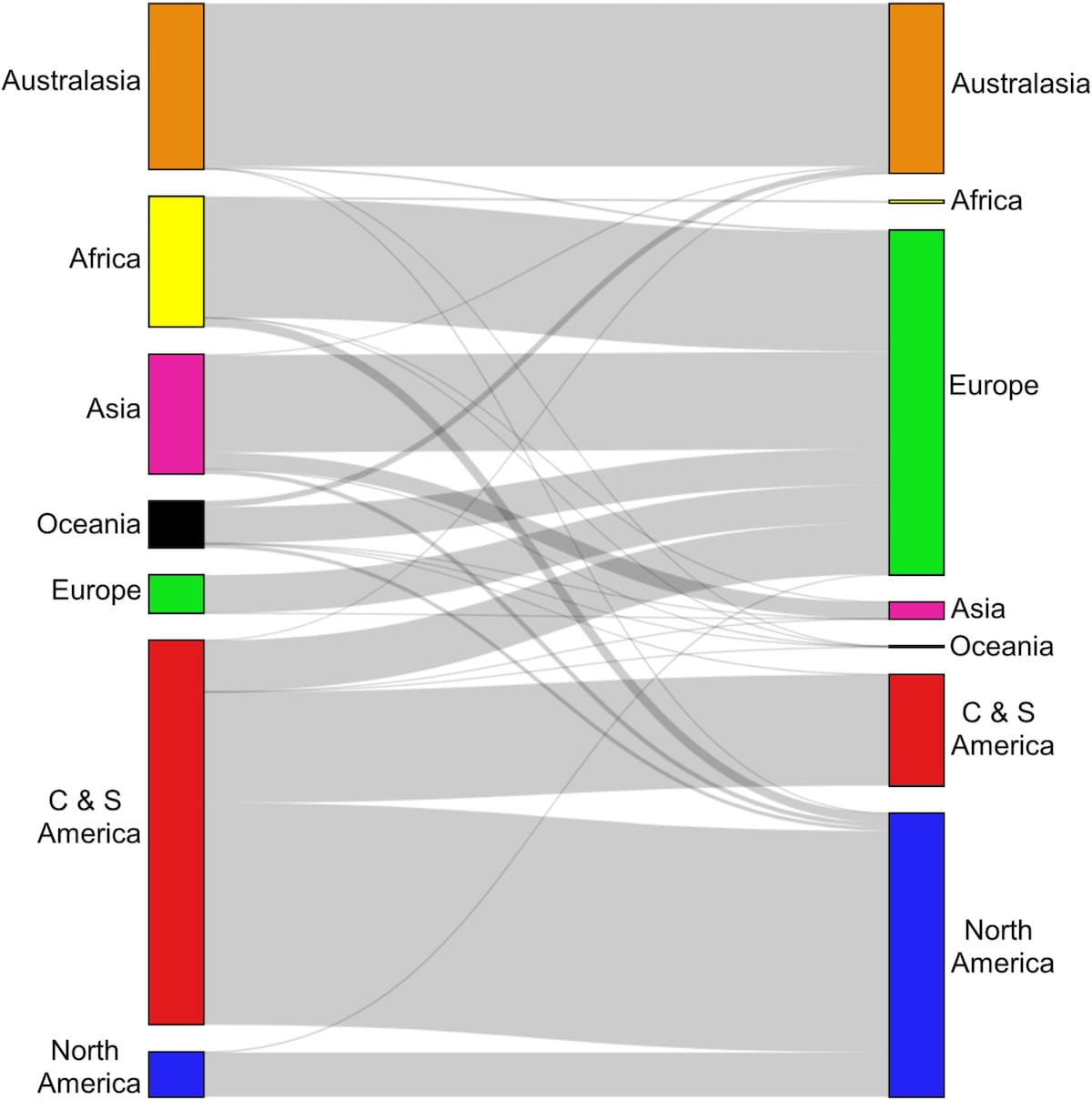

A new study led by Dr. Dominik Tomaszewski traced the journeys of over 119,000 holotypes from around 500 herbaria worldwide, following their path from the place of collection to the institutions that house them. The results are striking: these unique specimens have been historically stored far from where the plants were discovered, a practice that has only shifted over the past couple of decades.

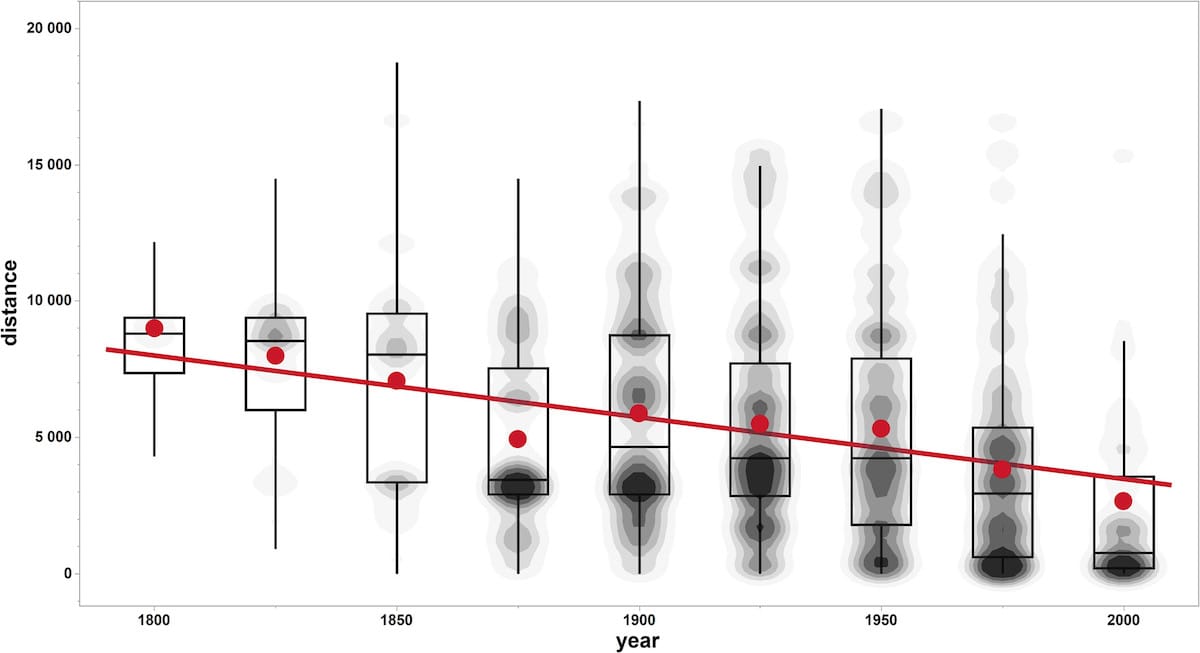

Tomaszewski’s team used the world’s largest open-access biodiversity database, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), to compile records of vascular plant holotypes—flowering plants, gymnosperms, and ferns. They examined specimens collected after 1800, linking each to two key details: where the plant was originally found and where it is stored today. Then, they calculated the distance between these two points, allowing them to track the flow of plant specimens across time and space.

Their data tells a fascinating, yet at times troubling, story. In the 1800s, when modern botanical collecting and herbarium techniques were taking shape in Europe, holotypes from biodiversity-rich regions like the Amazon or Madagascar were often shipped thousands of kilometres away to herbaria in Europe or, occasionally, North America. For instance, over 90% of African and Asian holotypes and 77% of those from Latin America are currently housed in herbaria outside their regions. Meanwhile, wealthier regions like Europe, North America, and Australasia have largely kept theirs close to home.

This pattern may seem natural, given that much of the world’s biodiversity was documented by botanical experts based in Europe and North America, often using specimens collected in the colonies. However, this disconnect between a plant’s origins and the location of its holotype creates real challenges for today’s botanists. Researchers in Africa, Asia, and Latin America who dedicate their careers to studying their own countries’ biodiversity often cannot access these specimens without travelling thousands of kilometres abroad, with all the financial, logistical, and administrative hurdles that such journeys entail.

However, this practice has begun to shift. Over the past 200 years, the average distance between where a plant is collected and where its holotype is stored has dropped sharply, from nearly 9,000 km in 1800 to around 750 km by 2000. Since the early 2000s, this trend has accelerated, with more and more holotypes being kept in their countries of origin. In Brazil, 60% of new holotypes remain local, a figure that goes up to 92% in Australia and New Zealand. Other countries, like Madagascar and Ecuador, still lag behind, but the gap is narrowing. So what’s behind this shift? The authors attribute this change to improved local infrastructure, stricter biodiversity laws, and greater global awareness of the need for scientific equity.

Digitisation is also changing the game. While physically moving specimens is difficult because they are delicate and irreplaceable, scanning and sharing high-resolution images of them online provides better access to scientists everywhere. Still, large portions of the global herbarium record remain offline or incomplete—especially in Asia and Africa—meaning the full picture is still out of reach. However, major research institutions are making tremendous efforts to digitise their collections. In the United Kingdom, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew has fully digitised 3.4 million specimens as of July 2024 and aims to complete all 7 million herbarium specimens by March 2026, turning Kew’s collections into a fully accessible global online resource.

Tomaszewski’s work shines a spotlight on how deeply plant science is shaped by geopolitics and history. Recognising these dynamics isn’t just an academic exercise, but an essential step toward making biodiversity science more just and globally inclusive. Hopefully, after tracing the travels of holotypes, this research helps us map a new future for botany.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Tomaszewski, D., Walas, Ł., & Guzicka, M. (2025). Tracing holotype trajectories: Mapping the movement of the most valuable herbarium specimens. Plants, People, Planet. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.70071

Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz

Erika is a Colombian biologist and ecologist passionate about tropical forests, primates, and science communication. She holds a Master’s degree in Ecology and Wildlife Conservation from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and has been part of Ciencia Tropical since 2020—a science communication group that aims to connect people with biodiversity and raise environmental awareness. You can follow her and her team on Instagram at @cienciatropical.

Spanish and Portuguese translation by Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz.

Cover Picture: Guioa misimaensis Welzen type. Photo by Naturalis Biodiversity Center (Wikimedia Commons).