The partnership between fig trees and fig wasps is one of nature’s most remarkable examples of mutualism —so fascinating that it’s often highlighted in our school textbooks! In this unique relationship, known as “obligate mutualism“, each species depends entirely on the other for survival. But did you know their intriguing bond revolves around two distinct pollination modes?

In active pollination, commonly seen in many American fig species, wasps become skilled pollen gatherers, using specialised structures to collect and transport pollen from one fig to another. This intentional process showcases the cleverness of wasps as they deliberately collect and deposit pollen. On the flip side, passive pollination takes a more serendipitous approach: as a wasp flits about inside a fig, it unwittingly picks up pollen and, just by chance, deposits it at other flowers without even trying!

These two pollination modes create fascinating differences in the shapes and structures of figs and wasps; each uniquely adapted to their specific strategies. Understanding these interactions does not just satisfy our curiosity about plant biology; it also reveals a remarkable story of mutualism, where species evolve together along their quest for survival.

To contribute to our understanding of this intricate relationship, Nadia Castro-Cárdenas and her team investigated how the physical characteristics of both fig flowers and wasps determine the occurrence of active or passive pollination. To study these interactions, they conducted fieldwork in a tropical forest reserve in Mexico. They focused on six fig species, three from each pollination type, and examined the anatomy of the wasps that pollinate them.

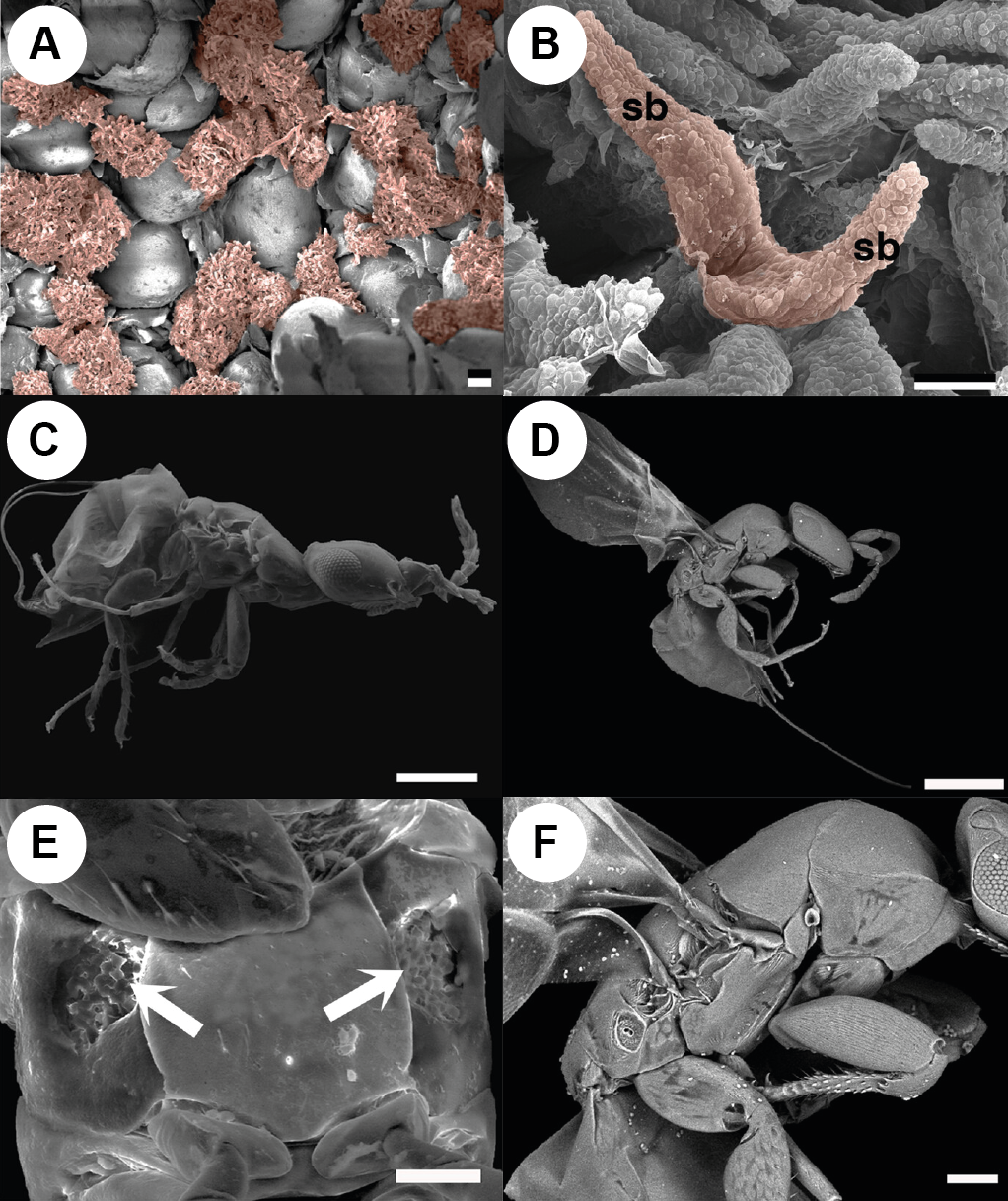

The research showed remarkable differences in how these species interact through two distinct pollination modes. In species where active pollination occurs, wasps from the genus Pegoscapus gather pollen with specialised structures called “pollen pockets” and “coxal combs.” In these figs, only a small percentage—about 5-10%—of the flowers within each syconium produce pollen, showcasing an efficient adaptation to this pollination strategy.

Contrastingly, species with passive pollination are more associated with wasps of the genus Tetrapus. In these cases, around 27-39% of the fig flowers produce pollen, indicating a different evolutionary approach. These notable differences highlight how each wasp and fig have co-evolved, resulting in unique adaptations that enhance their mutual survival.

The floral structures of these figs also vary significantly. In species with active pollination, the stigma –the structure where pollen needs to land to fertilise the ovule– of neighbouring flowers are fused in a single structure called the synstigma, which has hair-like projections that help capture pollen effectively. In contrast, passively-pollinated flowers have more widely spaced stigmas, which may contain compounds that attract specific wasps, optimising their chances of successful pollination.

Altogether, the research by Castro-Cárdenas highlights the complex evolutionary bond between figs and their wasp pollinators and shows how even minute differences in floral structure and wasp anatomy may have developed as specific adaptations. These adaptations highlight a unique balance, where both figs and wasps depend on each other to survive and reproduce, and underscore how finely tuned these mutualistic relationships are.

However, the research raises new questions: How much do these floral adaptations vary across the fig species’ extensive range? What specific traits are actively shaped by natural selection in figs and wasps? To answer these questions, broader studies that include a wider range of fig species are essential, along with the development of innovative research techniques.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Castro‐Cárdenas, N., Martén‐Rodríguez, S., Vázquez‐Santana, S., Cornejo‐Tenorio, G., Navarrete‐Segueda, A., & Ibarra‐Manríquez, G. (2024). Putting the puzzle together: the relationship between floral characters and pollinator morphology determines pollination mode in the fig–fig wasp mutualism. Plant Biology. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.13712

Victor H. D. Silva

Victor H. D. Silva is a biologist passionate about the processes that shape interactions between plants and pollinators. He is currently focused on understanding how plant-pollinator interactions are influenced by urbanisation and how to make urban green areas more pollinator-friendly. For more information, follow him on ResearchGate as Victor H. D. Silva.

Cover picture: Fig wasps Seres rotundus emerging from a Ficus abutilifolia syconium. Photo by Alandmason (Wikicommons).