Nectaries are the most interesting organs in flowers – at least to me. Compared to other floral organs (i.e. perianth organs, stamens and carpels), the position of nectaries is not necessarily fixed within the floral morphology. This makes them especially interesting to evolutionary studies. Additionally, and most importantly, nectaries produce nectar. In many angiosperm flowers, nectar is the primary reward offered to a potential pollinator. To ensure that ideally only legitimate pollinators can access the reward (and in that way successfully transfer pollen), flowers are often “built” around the nectary or the nectar. This is where floral architecture becomes important.

Floral architecture

Floral architecture is a term which is not commonly used. One reason for that might be that there are several terms describing various phenomena related to floral architecture. Some of these terms are focusing only on a specific aspect. Others are quite general and inclusive, but imprecise. I prefer the definition for floral architecture provided by Endress (1996). He differentiates between floral organisation and floral architecture. Under this definition, floral organisation describes the number and position of organs in a flower. Floral architecture describes and takes into account the relative sizes of floral organs, their degree of fusion and synorganisation (“spatial and functional connections between organs of the same or different kind leading to a homogenous functional structure”, (Ronse De Craene 2010, p. 412).

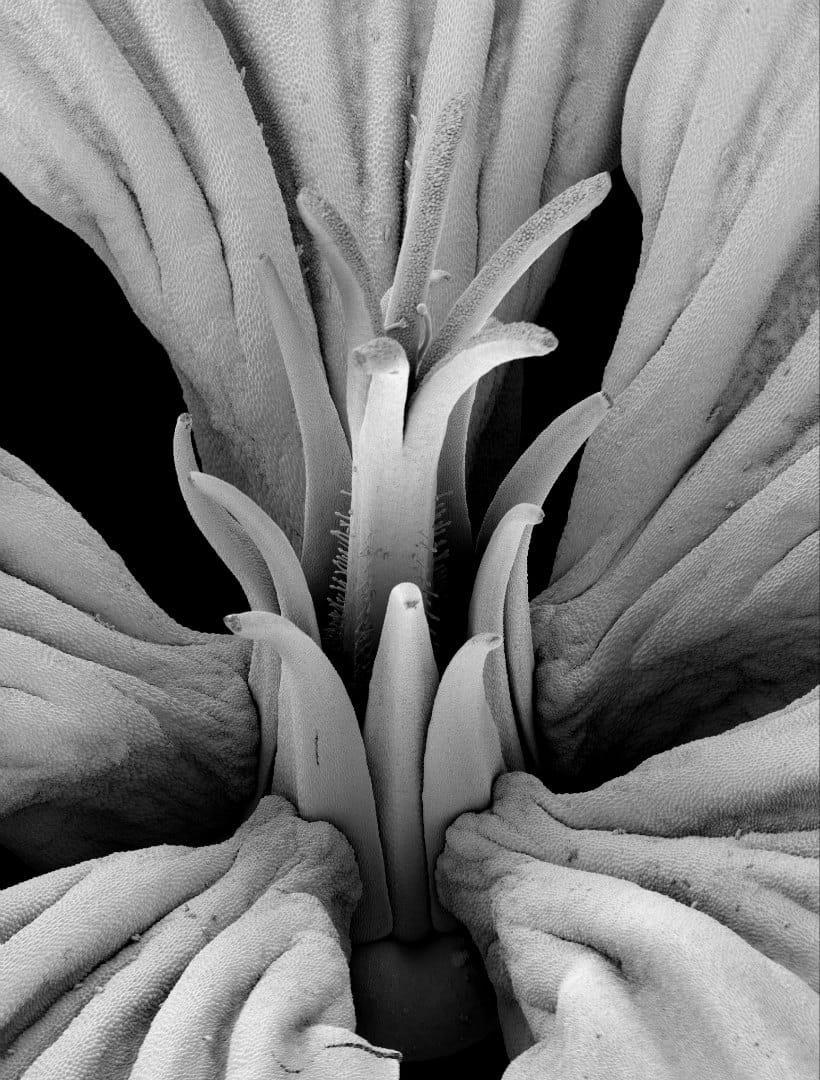

One illustrative example: borage (Borago officinalis) and viper’s bugloss (Echium vulgare) might look completely different at first glance (Figure 1). But if you break their appearance down to the number of organs, you will notice that their floral organisation is identical: 5 sepals, 5 petals, 5 stamens, 2 carpels, 1 nectary disk at the base of the ovary. What makes them appear different is, in fact, their floral architecture.

Geraniales – insights into nectaries and floral architecture

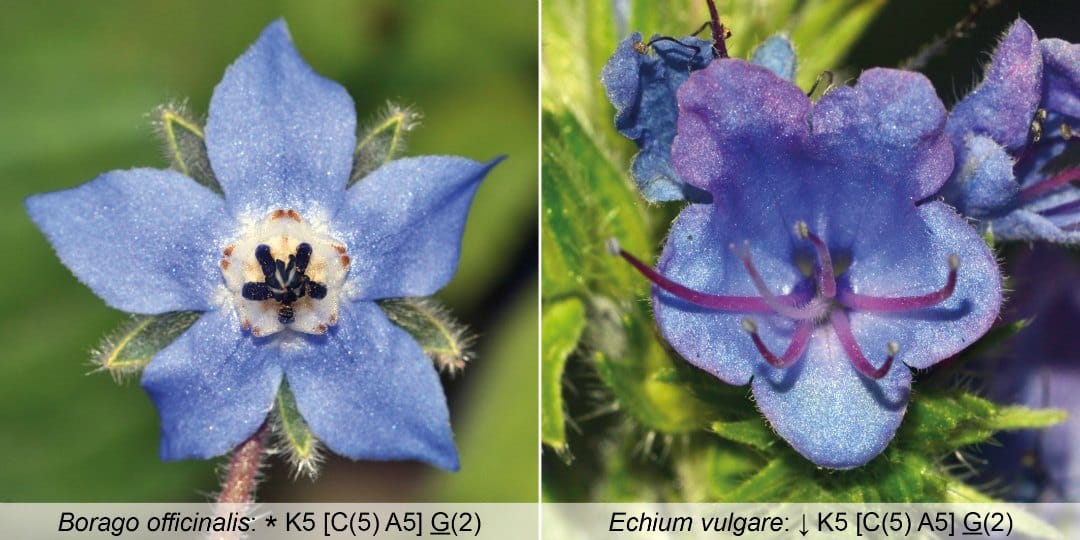

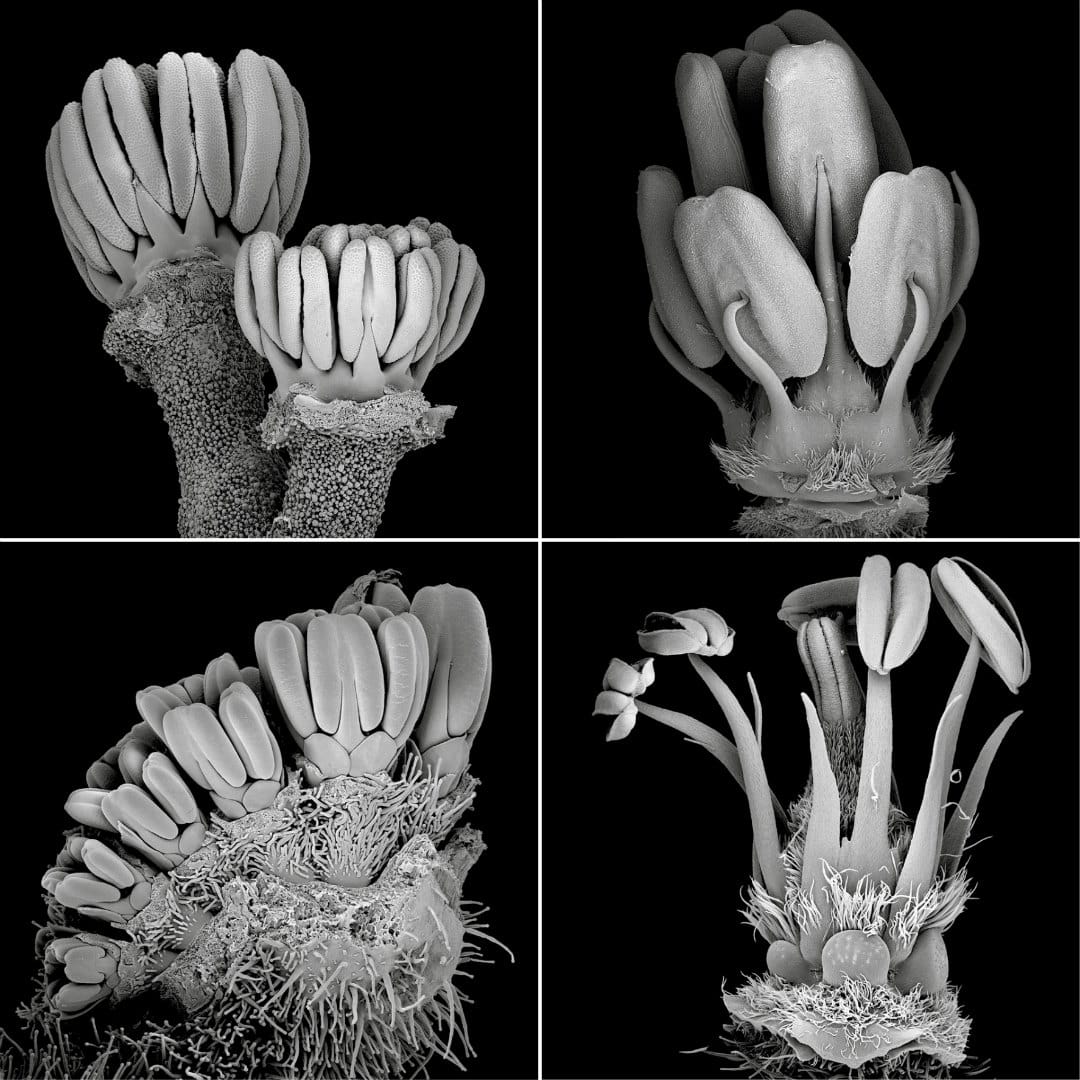

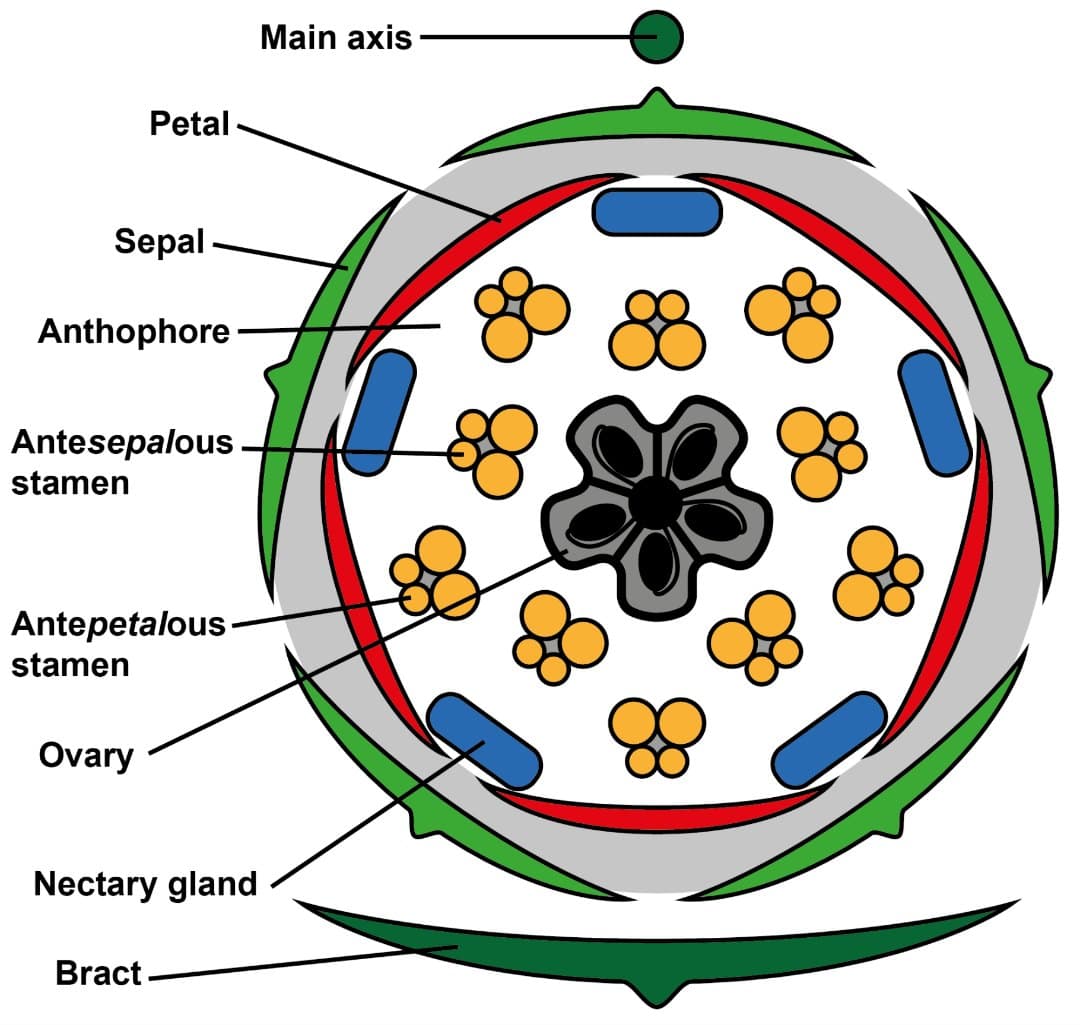

Geraniales are a particularly interesting group, where we studied the nectaries (Jeiter, Weigend, et al. 2017) and later the relationship between nectaries and floral architecture (Jeiter, Hilger, et al. 2017). Geraniales are a medium sized order with a sub-cosmopolitan distribution. Most of the species are placed in the family Geraniaceae with approximately 830 species. The remaining c. 45 species are included in four different families (Palazzesi et al. 2012). In our first paper (Jeiter, Weigend, et al. 2017), we studied the diversity in floral nectaries (Figure 2) and flower morphology. We found that despite huge differences in appearance (i.e., floral architecture), there is a high degree of similarity in floral organisation. Apart from switches in merosity (number of floral organs per whorl), major changes occurred in the androecium and to some extent in the corolla. We were able to show that changes in nectary gland number and position can be explained by simple shifts in their position in relation to the filaments. In this first article, we studied species from all genera of the whole order.

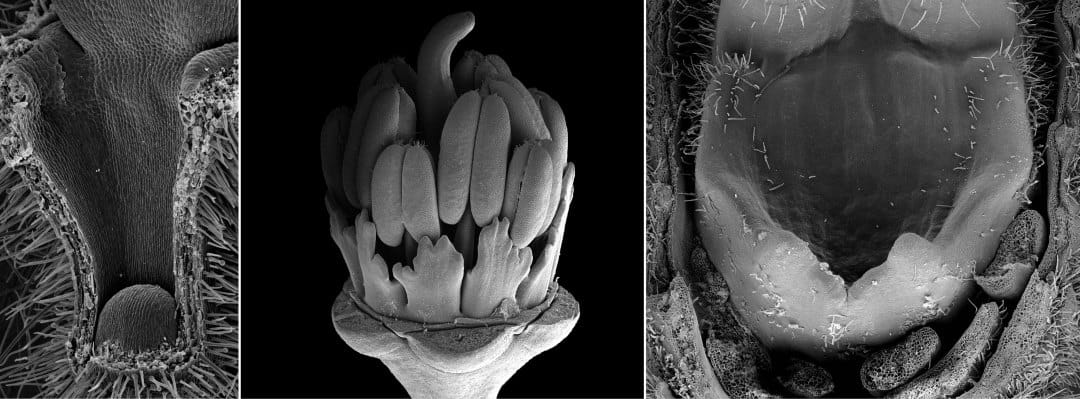

In our second article (Jeiter, Hilger, et al. 2017), we focused on the families Geraniaceae and Hypseocharitaceae (Figure 3). In these two families, differences in floral organisation occur in the number of fertile stamens and the number of whorls in the androecium. The only exception is the genus Pelargonium, showing a high degree of variability in the androecium (Figure 4), as well as in the perianth. We used an ontogenetic approach combining scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and light microscopy (LM) to study the development of the nectary glands and their relation to the other floral organs. We found that the nectary glands in all five genera studied arise in late flower development and are formed from the receptacle at the bases of the filaments of the antesepalous stamens. The receptacle is not only involved in the formation of the nectary glands, but also in changes in the floral architecture. The most prominent example is Pelargonium, where four of the five nectary glands, present in the other genera, are reduced. The remaining gland is placed in an elongated receptacular cavity easily mistaken for the petiole. In other genera, the receptacle forms a short, column-like structure, the so-called anthophore, lifting the inner floral organs, or the receptacle forms shallow invaginations, which partially enclose the slightly sunken nectary glands.

Revolver architecture

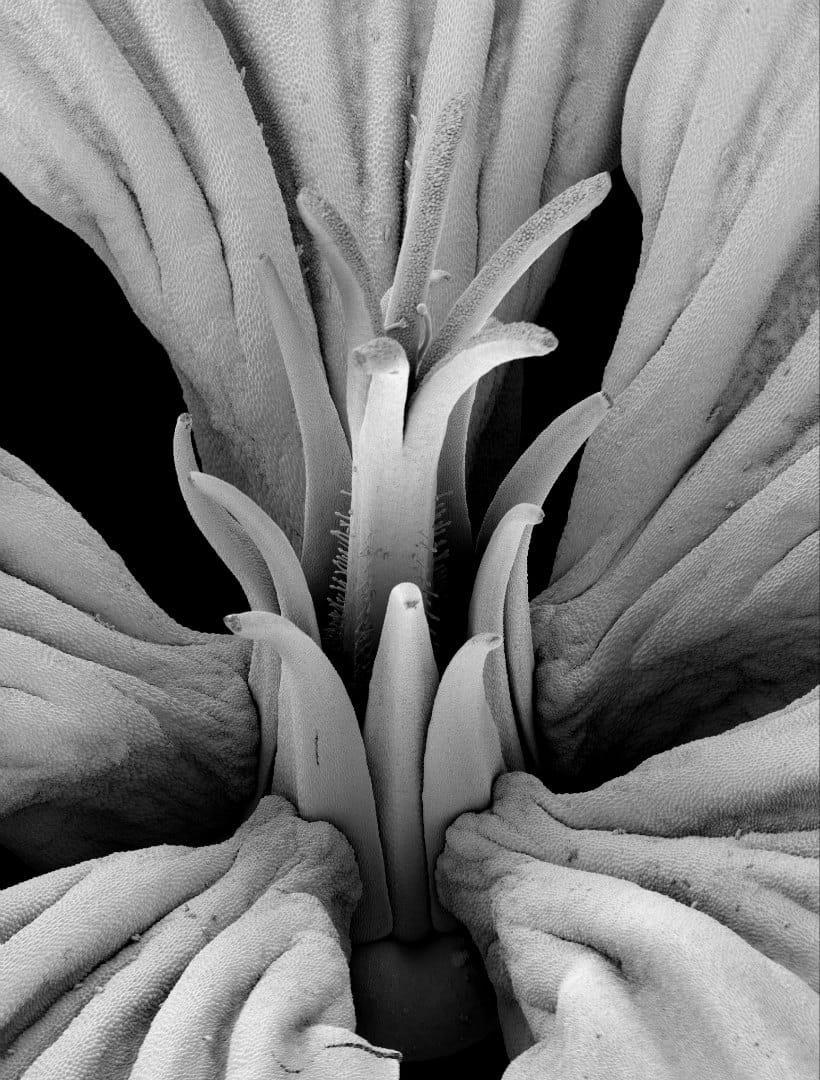

Floral architecture is strongly influenced by receptacular growth; however, the other organs of the flower are of course also involved and sometimes highly synorganised. Endress (2010) describes the formation of a revolver architecture in Geranium robertianum. Revolver architecture is a particular type of floral architecture, where separate compartments are formed. Each compartment holds part of the total nectar reward of the flower. As a consequence of revolver architecture, a potential pollinator has to probe every separate compartment to harvest all the nectar of the flower. This increases handling time and the movement of the pollinator on the flower (Video 1), which increases the likelihood of pollen being transferred and ultimately the seedset.