When it comes to understanding plant life on Earth, the collections of preserved plant specimens, commonly known as herbaria, are some of botany’s most powerful tools. Each specimen carries information about where and when a plant grew, what it looked like, and sometimes even how people used it. Together, they act as a global library of biodiversity, helping scientists identify species, track changes in ecosystems, and even uncover how climate change is reshaping nature.

Still, some herbaria go unnoticed by most researchers around the world. According to a recent study led by Dr. Daniel A. Zhigila and Ryan J. Schmidt-Knapik, many collections remain “silent”: unregistered in international directories, unknown outside their local institutions, and disconnected from global research. But this silence does not mean these herbaria are irrelevant, as they safeguard unique records of local plants, including species found nowhere else. Without their input, international studies risk missing critical pieces of the biodiversity puzzle.

One of the main tools for making herbaria visible to the global community is the Index Herbariorum, a global registry of plant collections. Being listed there makes a herbarium easier for scientists worldwide to find, collaborate with, and support. Since 2016, hundreds of new herbaria in the Global South have been registered, yet Africa seems to lag behind, representing only 6% of the more than 800 new entries. This disparity raises the question: are there truly fewer herbaria in Africa, or are they simply missing from the records?

Zhigila and Schmidt-Knapik’s research helps answer this question, using Nigeria as a case study. By conducting an extensive survey on the country’s herbaria, they found that 73% of the country’s 51 herbaria remain unregistered in the Index Herbariorum. It might be tempting to assume these are small collections, but in fact these silent herbaria preserve around 70% of Nigeria’s specimens. Moreover, the authors identified that only 20% of herbarium specimens in Nigerian collections have been digitized, and only 7% are digitally accessible via key biodiversity databases such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

So, if the problem is not that Nigeria lacks herbaria, why do they remain unnoticed? According to the study, more than 90% of Nigerian collections face severe financial limitations, leaving them without the climate-controlled storage or pest management systems needed to protect fragile specimens. In tropical countries, where heat, humidity, insects, and mold are constant threats, this neglect can mean the loss of irreplaceable biodiversity records. Even though Nigeria has one of Africa’s largest economies, the researchers found that most herbaria operate on minimal budgets, with little staff and infrastructure, often relying on their role in teaching rather than contributing to global science. This lack of resources is preventing Nigerian herbaria from digitizing their collections and making them widely available for researchers worldwide.

Local herbaria preserve specimens that simply do not exist elsewhere, especially more recent collections that track how plants are responding to current pressures such as deforestation, urbanization, and climate change. Because Nigerian scientists can collect year-round, their specimens also capture seasonal changes, such as flowering, that foreign collectors often miss. As a result, including Nigerian collections has the potential to provide a more accurate picture of plant life.

The team tested this idea with the medicinal plant Cnestis ferruginea. When they built a distribution model using only specimens housed outside Nigeria, the species’ range appeared to cover just a fraction of its true habitat. Adding data from Nigerian herbaria expanded the predicted range fivefold, showing just how much global science misses without these local collections. Therefore, Nigerian herbaria are not just duplicates of better-known collections abroad: they hold unique, irreplaceable records that are vital for understanding biodiversity and guiding conservation. By ignoring them, we risk incomplete or misleading science.

The way forward, the researchers argue, is to register every herbarium in global databases, invest in digitization, and strengthen local capacity with training and resources. Support could come from research grants, partnerships with industries that rely on biodiversity, or new national initiatives to protect collections. Such steps would not just preserve Nigerian plant specimens; they would amplify their importance on the world stage.

This research makes one point crystal clear: silent herbaria are not just a local issue, but a global one. By overlooking these collections, biodiversity science is working with an incomplete map of life. Nigeria’s example shows how integrating local herbaria into international databases can sharpen ecological models and improve conservation planning. The future of biodiversity research depends on breaking this silence through investment, digitization, and collaboration, so that herbaria everywhere can contribute their voices to a truly global conversation about the plants that sustain us all.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Zhigila, D. A., Schmidt‐Knapik, R. J., Thiers, B. M., Abdul, S. D., Abdullahi, S., AbdulRahaman, A. A., … & Davis, C. C. (2025). Biodiversity science is improved when silent herbaria speak. Plants, People, Planet. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.70091

Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz

Erika is a Colombian biologist and ecologist passionate about tropical forests, primates, and science communication. She holds a Master’s degree in Ecology and Wildlife Conservation from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and has been part of Ciencia Tropical since 2020—a science communication group that aims to connect people with biodiversity and raise environmental awareness. You can follow her and her team on Instagram at @cienciatropical.

Spanish and Portuguese translation by Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz.

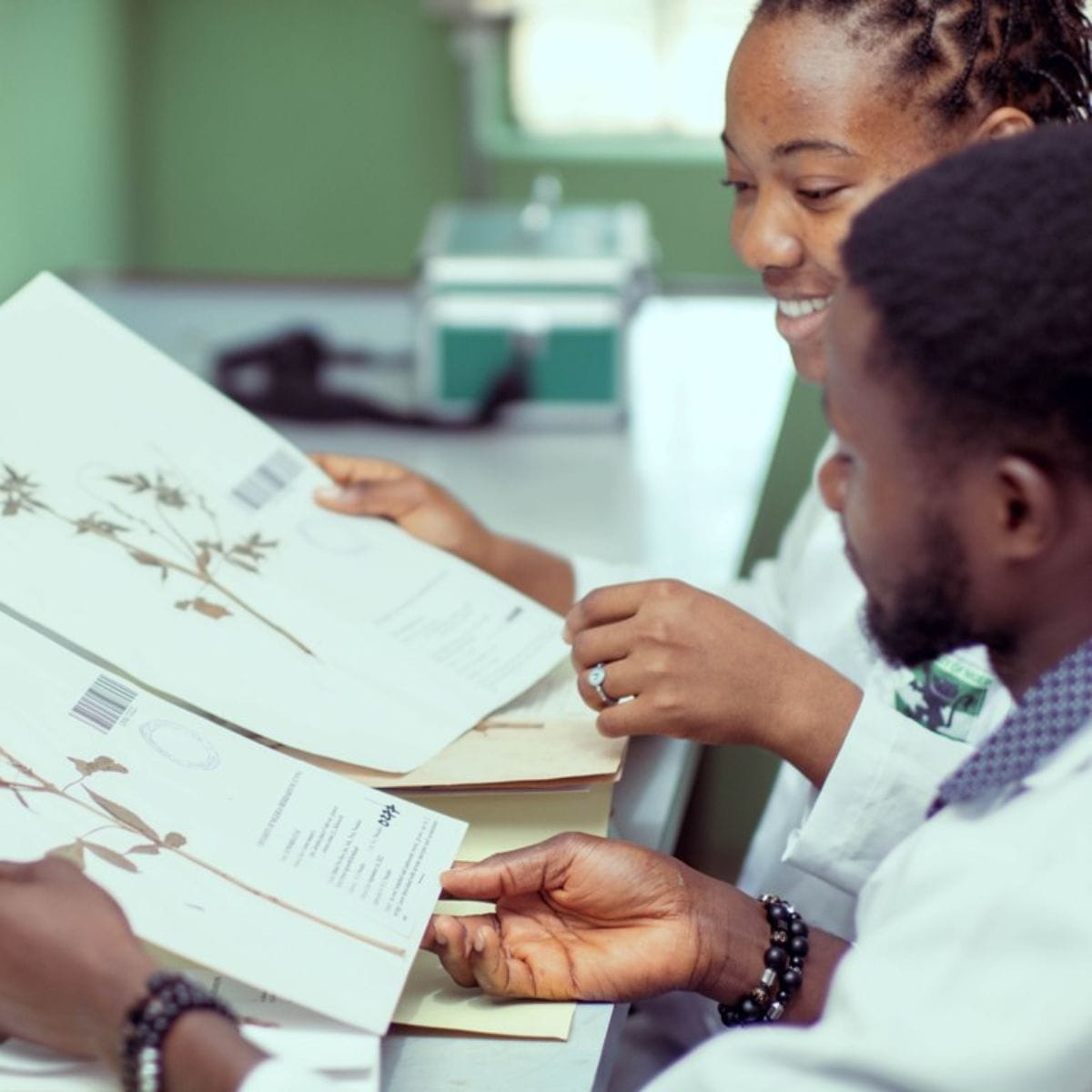

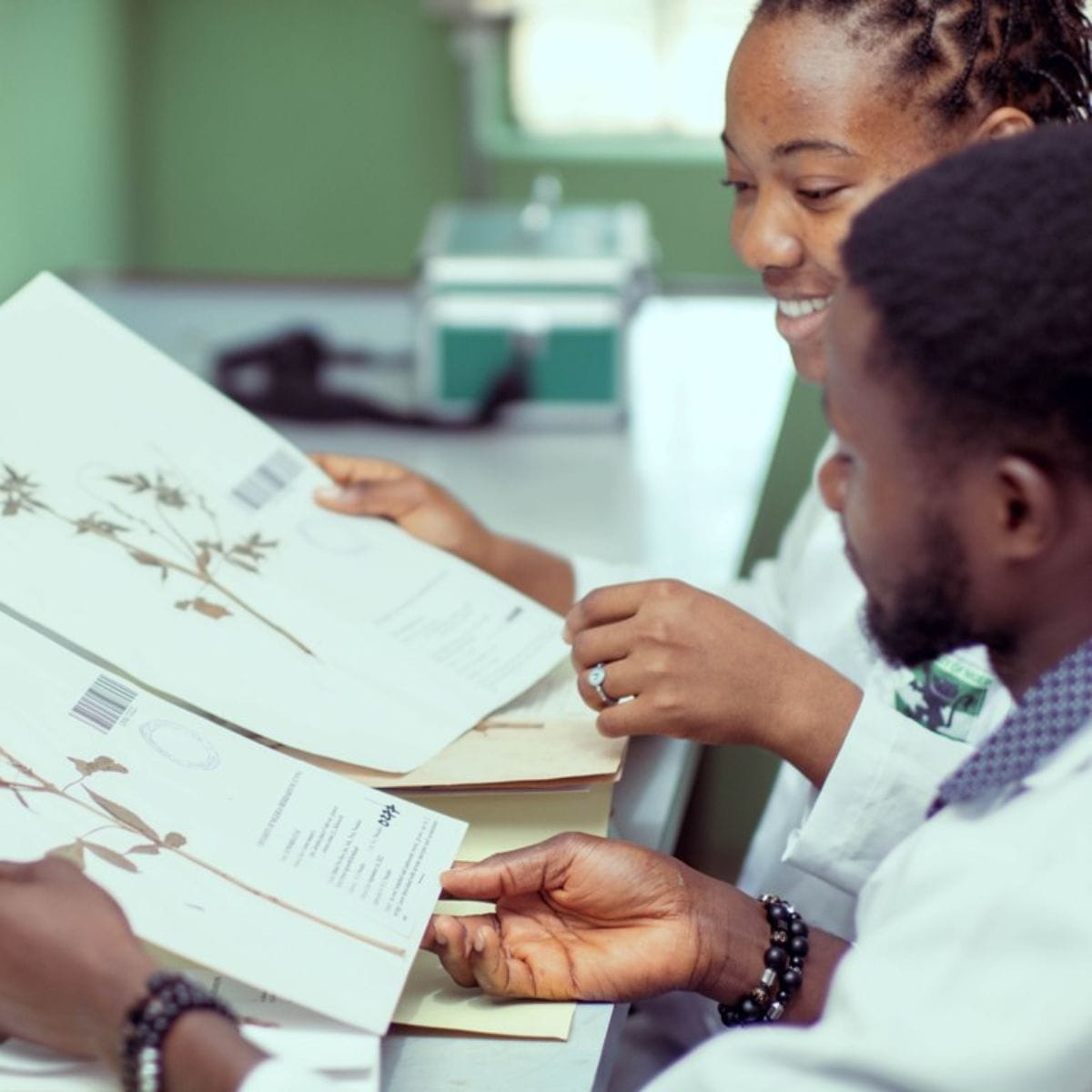

Cover picture by the University of Nigeria Herbarium (UNN).