Can the smell of a lemon balm leaf define the course of a life? Although for most people it is just a pleasant scent in the garden, for one of the participants in a recent study, that smell was the initial spark: a childhood attempt to “make a perfume” with that plant became the first step of a scientific career.

We often think of science as a discipline of cold data and rigorous logic. However, if we ask botanists why they do what they do, the answer is rarely an equation but a memory. It is planting marigolds with a great-grandmother or seeing plant tissue cultures for the first time. In fact, the recent study by Dr Joanna Kacprzyk and Dr Rainer Melzer, researchers at University College Dublin, which asked 421 plant biologists what motivated them to choose this path, found that the number one reason was not civic duty, but a deep emotional connection.

Through open-ended questions, the researchers sought personal narratives: asking them to share their educational motivations, career pathways, and cherished plant-related memories. The results showed that “curiosity” and an “appreciation for plants” and their beauty were the primary drivers. For instance, many respondents simply cited that they “always loved plants” or found them “beautiful and intriguing”. Another key motor was a fascination with “plant physiology, genetics, and adaptation mechanisms,” often sparked by “hands-on experiences” in laboratories or field trips.

However, it wasn’t always love at first sight. The study reveals that serendipity also plays a major role. Some did not plan to be botanists but stumbled into the profession by accident, perhaps through an available student placement or an unexpected vacancy, and ended up staying, captivated by what they discovered along the way.

Beyond intellectual curiosity, there was also a longing for freedom; for many, botany offered the perfect excuse to work outside rather than in an office. Other scientists chose botany for ethical reasons, preferring to avoid animal-based research. These scientists explicitly cited discomfort with animal dissection or being squeamish about blood as motivating factors. This is a reminder that science is also shaped by who we are as people.

Yet, these personal inclinations rarely bloom in isolation; they often need someone to plant the seed. The study highlights that having a plant mentor is a crucial factor, a role often filled by passionate university-level lecturers or the family itself. Interestingly, home influence is vital; female respondents cited family members as mentors significantly more frequently than males. This suggests that the scientific vocation is planted through shared memories with parents or grandparents, years before stepping into a university lecture hall.

The conclusion of the authors is a call to action for all communicators and educators. If we want a new generation of plant scientists to fight climate change and biodiversity loss, it is not enough to overwhelm them with data about the crisis. We need a “multiple-touchpoint outreach strategy” that combines experiential learning, the presence of passionate educators and family members, and an emotional bond with the beauty and wonder of plants.

As the study summarises: “It is important to not only win the minds of future plant biologists… but to also win their hearts”.

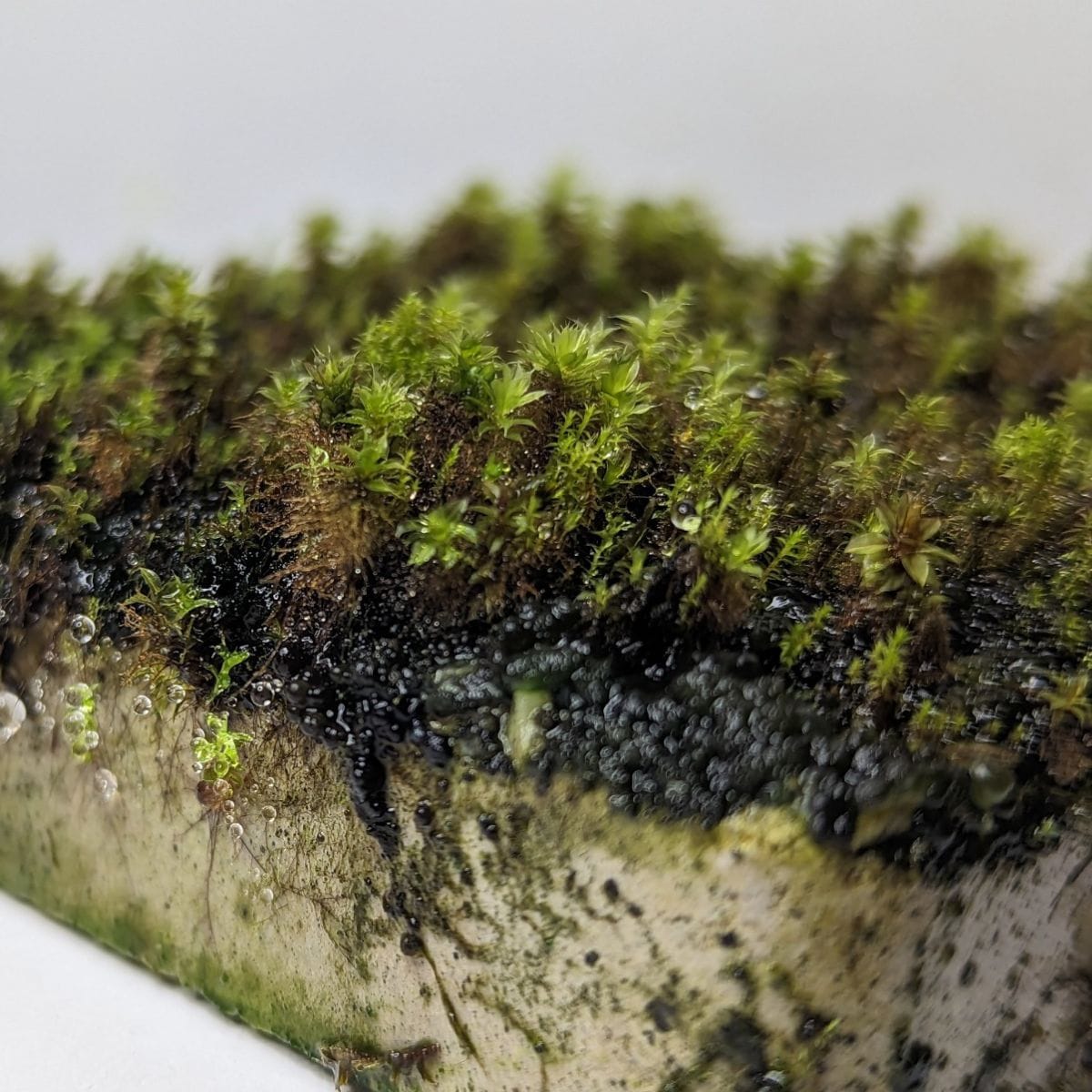

Do you have a specific memory with a plant that changed how you view the world? A particular smell, the touch of moss, or the first time you saw a seed germinate? Perhaps, without knowing it, you already have the heart of a botanist.

READ THE ARTICLE

Kacprzyk, J., & Melzer, R. (2025). Inspiring the next generation of plant scientists: What we learned from 421 plant biologists. Plants, People, Planet, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.70156

Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz

Erika is a Colombian biologist and ecologist passionate about tropical forests, primates, and science communication. She holds a Master’s degree in Ecology and Wildlife Conservation from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and has been part of Ciencia Tropical since 2020—a science communication group that aims to connect people with biodiversity and raise environmental awareness. You can follow her and her team on Instagram at @cienciatropical.

Spanish and Portuguese translation by Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz.

Cover picture by Anderson Butte (Wikimedia Commons)