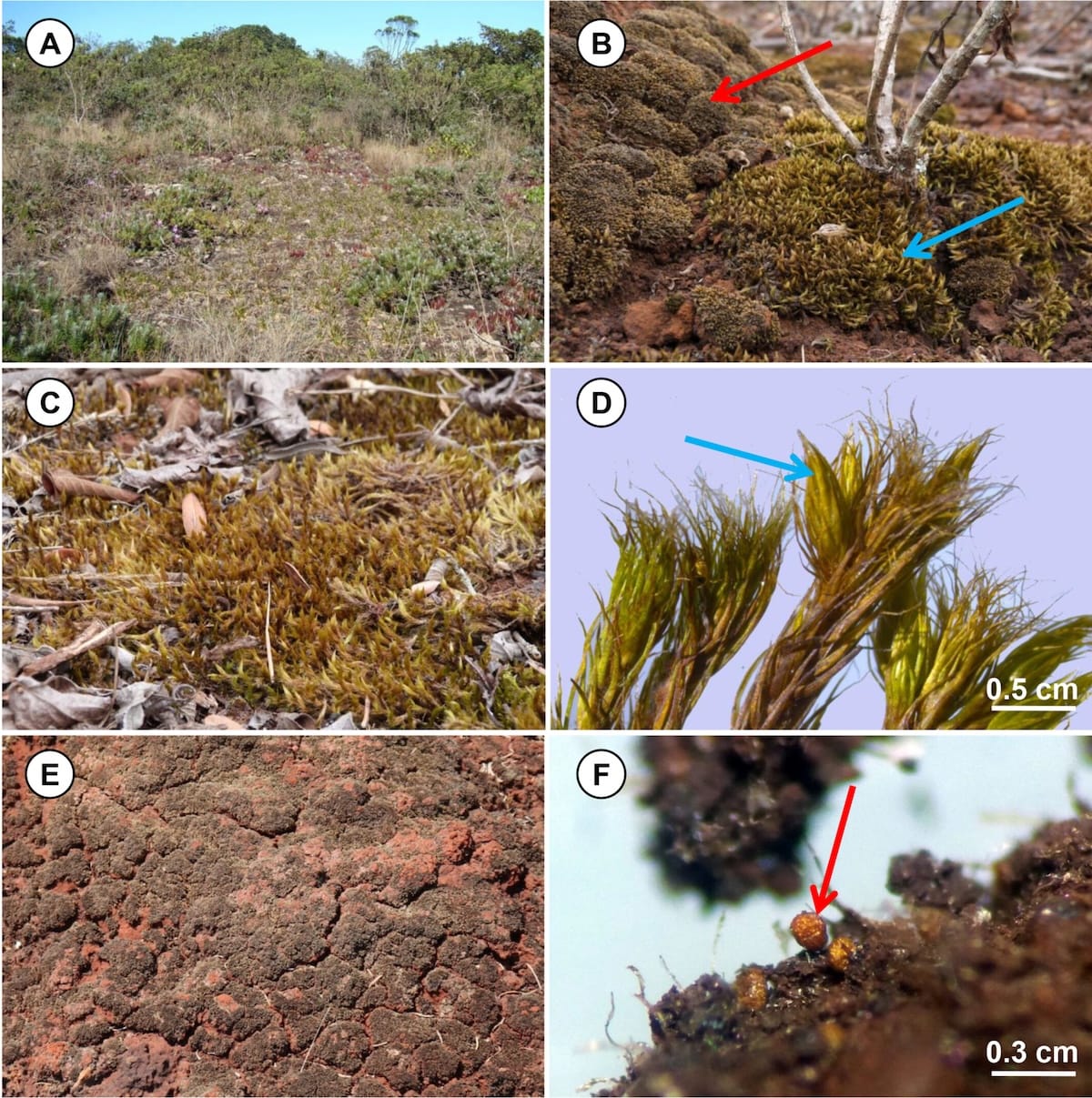

Will global warming mark the end of plant diversity as we know it? Perhaps not if we learn from organisms that already live on the edge. Arid, rocky, and scorching regions, for example, may seem inhospitable, yet even in these hostile settings, nature finds ways to thrive. Such is the case of the Brazilian Cangas, unique ferruginous formations in southeastern Brazil, known for their extremely nutrient-poor soils, intense solar radiation, and frequent wildfires, during which temperatures can exceed 500 °C. Despite this, these ecosystems host a unique flora composed of angiosperms, lichens, liverworts, and mosses that can withstand extreme heat and drought.

But how far does this resilience go? That was the question that motivated the study by Guilherme Freitas Oliveira and colleagues, recently published in Austral Ecology, which tested, for the first time, the heat tolerance of the structures used for vegetative reproduction in Bryum atenense and Campylopus savannarum, two mosses characteristic of the Cangas. The team exposed these structures to temperatures of 120 °C, 140 °C, and 160 °C for periods of 5 and 30 minutes, simulating the thermal impact of natural fires in the Cangas. For instance, the exposure of 160 °C for 5 minutes reproduced the rapid passage of flames during a wildfire, allowing the researchers to correlate moss resistance with real fire events.

The results are striking. The phyllids of Campylopus savannarum were used in the experiment but did not survive any of the treatments, evidencing their high sensitivity to heat and suggesting that this species is vulnerable to the direct impacts of fire. In contrast, the subterranean tubers of Bryum atenense showed extraordinary resilience. Even after exposure to 160 °C for 5 minutes, a temperature sufficient to carbonise most plants, about 58% of the tubers produced new tissues. Moreover, at 120 °C for 30 minutes, regeneration exceeded 60% of the samples. As a result, these underground structures act as true biological vaults resistant to extreme heat, representing a remarkable adaptation for surviving fire.

The study recorded the highest level of thermotolerance ever known for bryophyte propagules, showing how microscopic strategies ensure survival in severe environments. The resistance observed in Bryum atenense may be linked to the presence of lipid compounds that act as thermal insulators and to the low moisture content of the tubers, both of which reduce cellular damage. The authors also suggest the involvement of heat shock proteins and stress-response genes, like those found in desert mosses such as Syntrichia caninervis. Understanding these mechanisms may reveal how the genes of the first land plants cope with extreme heat and, in the future, inspire genetic improvement strategies to make cultivated species more heat-resistant.

More than explaining how these mosses survive wildfires, the study offers a new perspective on plant adaptation to global climate change. Because many bryophytes are sensitive to rising temperatures, understanding their thermotolerance is crucial for predicting which species may disappear and which may persist. Bryum atenense, by showing such excellent resistance, proves that evolution has already found ingenious solutions to withstand heat. Their invisible tubers hold not only the next generation but also the story of resistance of an ecosystem forged in heat and, perhaps, the clues to the future of plants on a warming planet.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Oliveira, G. F., Oliveira, M. F., Araújo, C. A. T., & Maciel‐Silva, A. S. (2025). Thermotolerance in Miniature: Heat Resilience of Moss Propagules From Brazilian Ferruginous Rocky Outcrops. Austral Ecology, 50(9), e70121.

Pablo O. Santos

Pablo is a PhD student in Plant Biology at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Brazil), where he conducts research on photoprotective strategies and antioxidant potential of bryophytes from ferruginous outcrops. His research interests lie at the intersection of physiology, ecology, and phytochemistry of bryophytes, with an emphasis on the ecological role and biotechnological applications of liverworts, mosses, and hornworts.

Portuguese Translation by Pablo O. Santos.