Ecological restoration is one of the greatest challenges of our time. But how can we recover degraded areas and bring life back to soils that have lost their ability to sustain ecosystems? Scientists have been searching for creative alternatives, and a group of Brazilian researchers has presented a surprising solution: encapsulating biocrust organisms in small alginate beads, tiny gel-like capsules made from seaweed-derived compounds that can protect and gradually release living organisms, turning them into true “packages of life” capable of accelerating the recovery of degraded areas.

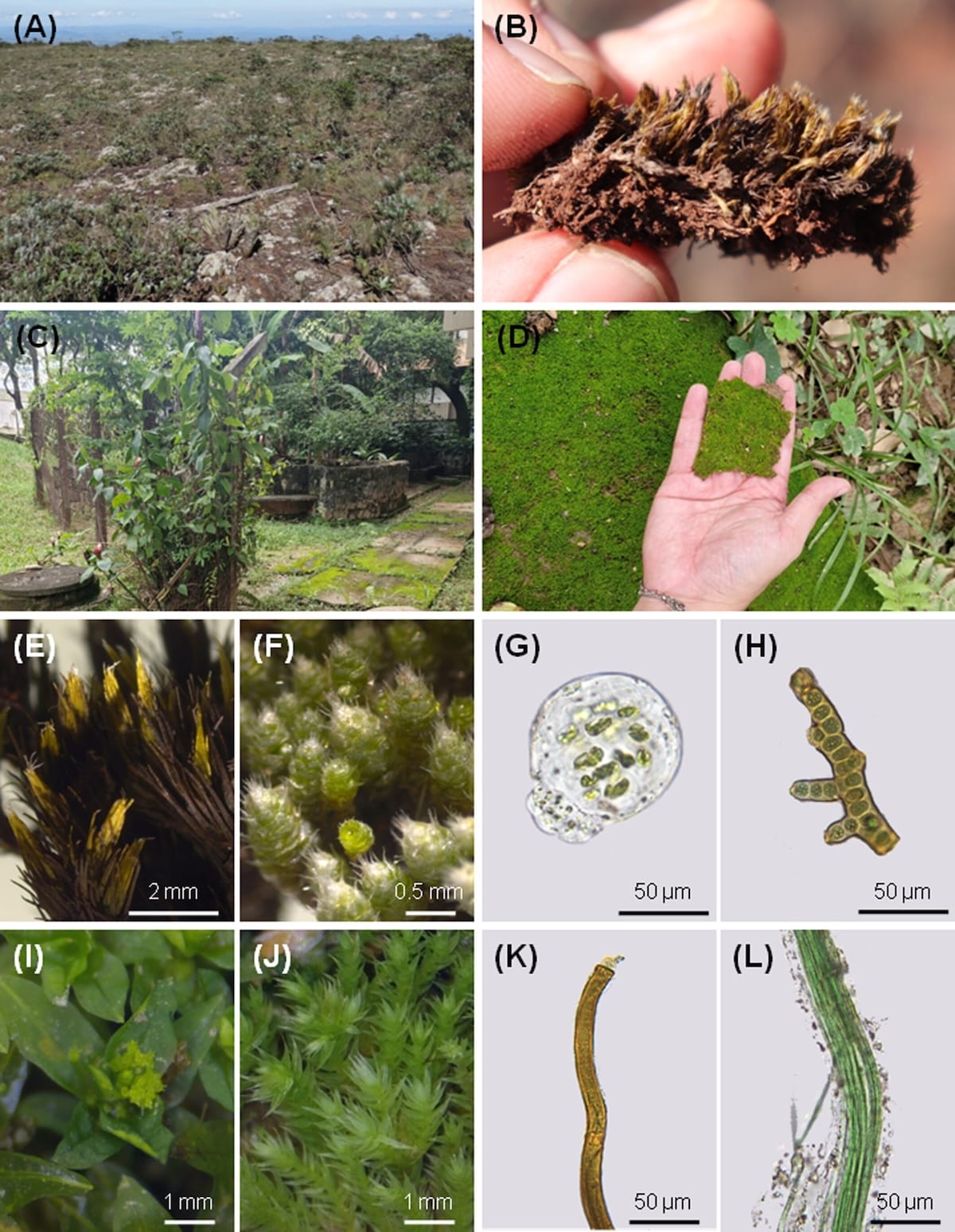

A study led by Mateus Oliveira and colleagues published in Restoration Ecology, presents an innovative protocol for the inoculation of biocrusts, communities formed by cyanobacteria, algae, lichens, and especially bryophytes. Despite being tiny in appearance, these biological crusts act as true ecosystem engineers, as they stabilize soil particles, increase water retention, fix carbon and nitrogen, and create the initial conditions that allow other plants to establish. However, putting this potential into real restoration practice is not simple: erosion, burial by sediments, and lack of essential resources such as water and nutrients often compromise the survival of inoculated organisms. At this point, bioengineering with alginate beads emerges as a promising alternative.

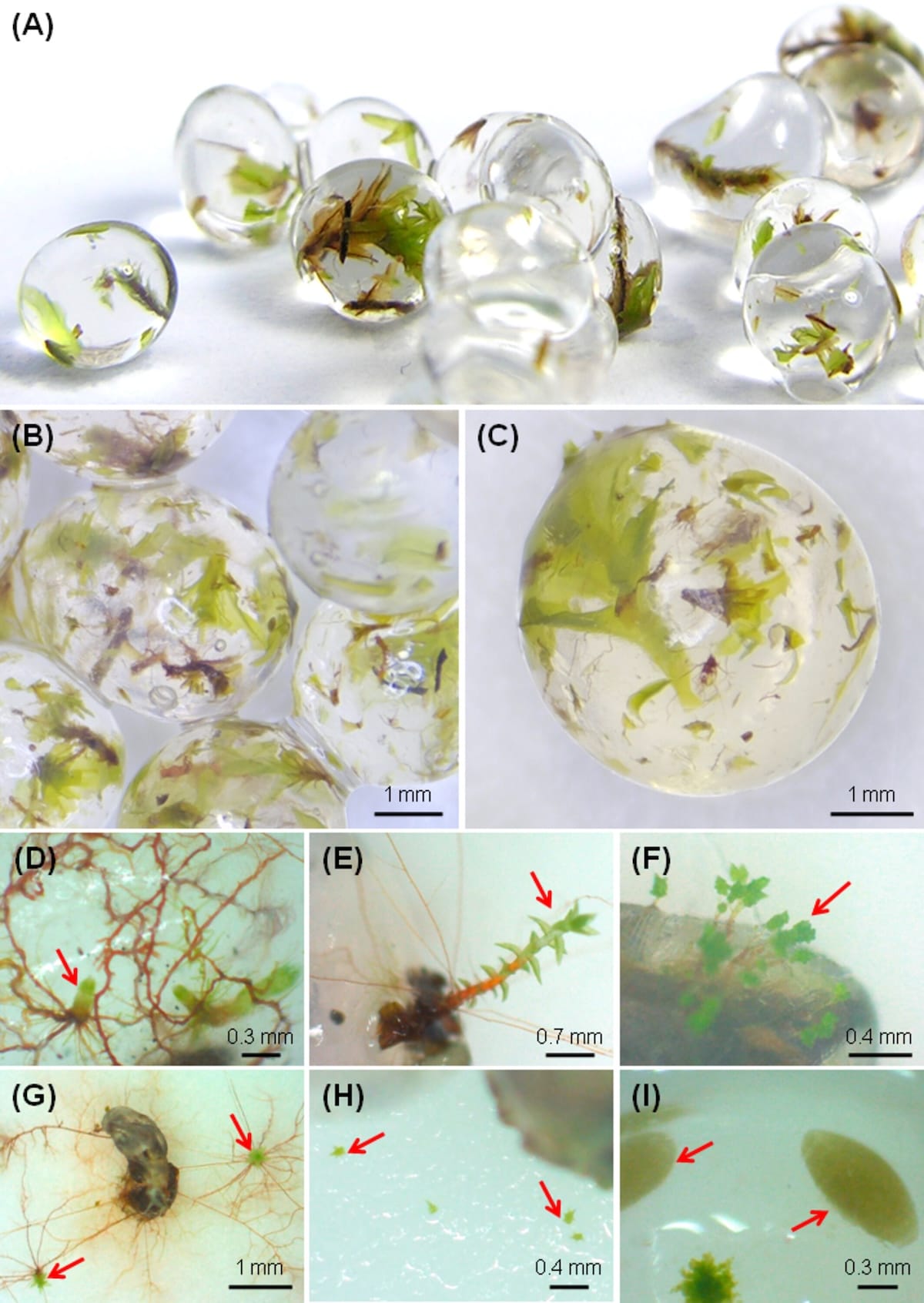

The protocol developed by Oliveira and colleagues involved encapsulating fragments of mosses and their associated organisms in alginate beads enriched with nutrients and starch, producing uniform structures 3-4 mm in diameter. Among the species used were mosses common in open and degraded areas, such as Bryum argenteum and Hyophila involuta, accompanied by algae of the genus Gloeocystis and cyanobacteria such as Scytonema and Microcoleus.

After only 21 days of cultivation in the lab, the beads already showed complete establishment, with the development of rhizoids and even the formation of new gametophytes and gemmae, bryophytes sexual and asexual propagation structures, respectively. The moss Hyophila involuta was a particular success. These findings showed that the method not only keeps the organisms alive but also favors their multiplication and dispersal. Even more impressive, viability tests revealed that these “biocrust seeds” preserved more than 70% of their establishment potential even after one year stored under refrigeration, demonstrating that they can be produced, transported, and used on a large scale without significant loss of effectiveness.

The potential of this approach for environmental restoration is immense. Imagine being able to restore riverbanks, erosion-prone slopes, or mining areas by applying thousands of small beads that carry, inside, entire communities capable of recreating living soils. Unlike more expensive and complex methods that require large infrastructure, alginate beads offer a practical, low-cost, and highly scalable alternative. In addition, the presence of nutrients and starch in their formulation helps provide energy and moisture in the early stages of development, increasing the chances of success in establishing biocrusts. This strategy, at the same time simple and ingenious, can be integrated with other techniques already in use, such as biodegradable adhesives and irrigation management, making restoration projects more efficient and long-lasting.

For the future, the authors highlight the importance of taking the protocol from the laboratory to the field, testing its effectiveness in real environments subject to stressful conditions such as temperature variation, water deficit, and strong winds. Even so, the study already represents a remarkable advance, as it offers a concrete tool to incorporate bryophytes and other components of biocrusts into ecological restoration programs. Encapsulating life in beads so small shows how innovative solutions can arise from observing and harnessing the smallest engineers of nature. The message that emerges is clear: restoring degraded ecosystems can begin with microscopic steps, but each of them carries a potentially gigantic impact for the future of biodiversity and the resilience of natural environments.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Oliveira, M. F., Santos, P. O., Oliveira, R. R., Figueredo, C. C., & Maciel‐Silva, A. S. (2025). Encapsulating ecosystem engineers: alginate beads of biocrusts for restoration efforts. Restoration Ecology, e70141. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.70141

Pablo O. Santos

Pablo is a PhD student in Plant Biology at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Brazil), where he conducts research on photoprotective strategies and antioxidant potential of bryophytes from ferruginous outcrops. His research interests lie at the intersection of physiology, ecology, and phytochemistry of bryophytes, with an emphasis on the ecological role and biotechnological applications of liverworts, mosses, and hornworts.

Portuguese Translation by Pablo O. Santos.