Mexico boasts two great treasures: immense biological diversity and cultural diversity. Not only is it one of the 17 megadiverse countries, but it is also home to 71 ethnic groups and speakers of more than 62 Indigenous languages. However, this immense biocultural diversity is under threat, as many of these languages are falling into disuse, taking with them centuries of ecological knowledge. As a result, efforts to safeguard both the species and the cultural wisdom that describe and sustain them have taken on new urgency.

A recent study published in Plants, People, Planet presents a decade-long research project to document and conserve the fungal diversity closely linked to the Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo, a community in the mountains of central Mexico. Within the country’s great biodiversity, Mexico stands out for its remarkable variety of edible fungi, around 500 reported species, a total surpassed only by China. The Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo are at the very forefront of this heritage, with earlier studies reporting up to 70 fungi species in use, a figure now shown to have vastly underestimated their true knowledge. Yet this treasure trove of knowledge is at risk of vanishing, as only 50 elders still speak the community’s native language.

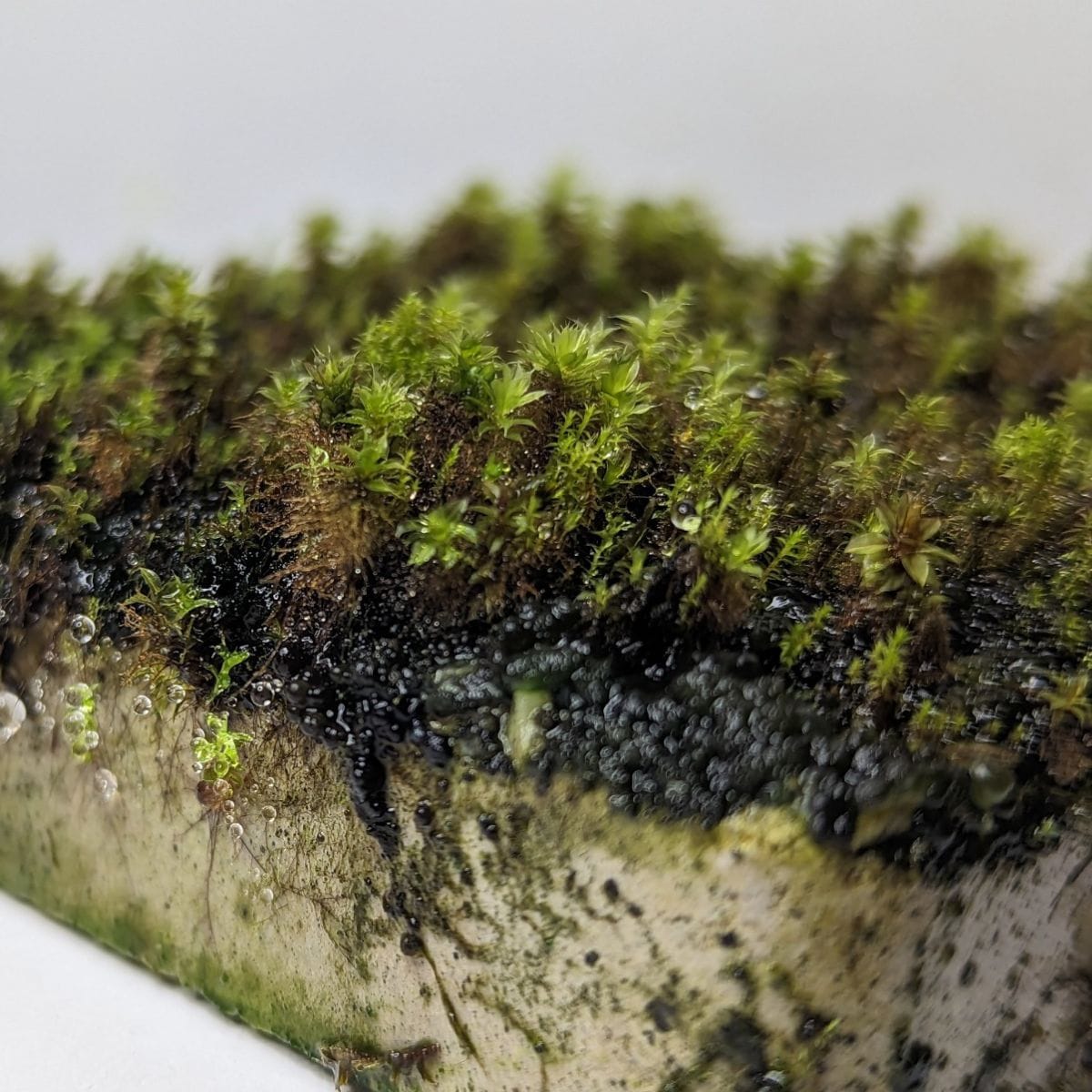

The research team immersed themselves in the Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo community of Lomas de Teocaltzingo and, over ten rainy seasons between 2013 and 2023, went into the field with the community’s most knowledgeable mushroom gatherers, known locally as hongueras and hongueros. When a mushroom was found, it was carefully photographed, collected, and described. These specimens were also shown to local residents to gather information on their names in both Spanish and the Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo language, the times of year they appear, how they are cooked, and where they grow. This approach allowed the researchers to document not only the fungi’s biodiversity but also the cultural knowledge that surrounds it.

The study revealed that the community’s mushroom expertise far exceeded earlier estimates: researchers identified 202 species of wild edible fungi that the Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo gather and eat, more than any other ethnic group documented worldwide, surpassing even mushroom-rich regions of China and Eastern Europe. Among these were 23 species that do not appear in the most comprehensive global reviews on the subject, including entirely new records for edibility and preparation techniques unknown to science, such as safely cooking the renowned and toxic Amanita muscaria.

These mushrooms are more than food. Many are rich in protein, vitamins, antioxidants, and medicinal compounds that can help with everything from inflammation to digestive issues. Some even have potential uses in pharmaceuticals and natural pesticides. The community’s mushroom vocabulary is as rich as its forests, with names in both Spanish and the Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo language inspired by shape, colour, smell, taste, and even resemblance to local animals or plants. They also hold precise knowledge of where and when each species appears and pass this information down carefully within families. Some collection sites are guarded secrets, especially for prized species like morels (Morchella) and certain boletes (Boletus). Notably, the community has not recorded any cases of mushroom poisoning in decades, a testament to the precision of their knowledge.

The team also identified 27 species with high international gourmet value. By harvesting and selling these sustainably, the authors argue the community could boost its economy while protecting local forests. To this end, scientists and community members have worked together for over a decade to preserve and share traditional mycological knowledge. Initiatives include mushroom fairs, cooking classes, sustainable harvesting workshops, and “mycotourism”, which guided walks to collect and learn about wild mushrooms. These events attract visitors from around the world and create income while keeping the culture alive. Perhaps most importantly, the Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo themselves are leading these efforts, blending scientific collaboration with cultural autonomy. For instance, Elisette Ramírez-Carbajal, lead author of the paper, is also Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo. Their success shows how safeguarding traditional ecological knowledge can support biodiversity, food sovereignty, and sustainable development.

The Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo story is more than a catalogue of mushrooms: it’s a testament to how deeply human cultures can be entwined with their environments, and how much the world stands to lose when such knowledge fades. This decade-long collaboration has shown that preserving mycocultural heritage isn’t just about recording names and recipes; it’s about sustaining language, identity, and the intricate relationships that have evolved over centuries. By documenting new edible species, safeguarding traditional preparation techniques, and fostering economic opportunities through sustainable use, the Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo remind us that heritage is not just something to be preserved: it is something to be lived, shared, and carried forward.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Ramírez‐Carbajal, E., Martínez‐Reyes, M., Ayala‐Vásquez, O., Fabiola, R. E., Lagunes Reyes, M., Hernández‐Santiago, F., … & Pérez‐Moreno, J. (2025). Revitalizing endangered mycocultural heritage in Mesoamerica: The case of the Tlahuica‐Pjiekakjoo culture. Plants, People, Planet. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.70014

Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz

Erika is a Colombian biologist and ecologist passionate about tropical forests, primates, and science communication. She holds a Master’s degree in Ecology and Wildlife Conservation from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and has been part of Ciencia Tropical since 2020, a science communication group that aims to connect people with biodiversity and raise environmental awareness. You can follow her and her team on Instagram at @cienciatropical.

Spanish and Portuguese translation by Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz.