Climate change is no longer a distant threat; it is shaping our seasons, redrawing ecosystems and rewriting the rules of life on Earth. One of its most visible consequences is the steady rise in global temperatures. But heat brings more than discomfort, it brings fire. Wildfires are becoming more frequent and intense. These blazes do not just scorch the landscape: their smoke spreads far and wide, lingering in the air and blocking sunlight for days or even weeks.

Biodiversity is feeling the strain. And although we might not notice at first, pollinators and their relationship with plants are also under this pressure. Bees are adjusting their behaviour in response to warming, with the main changes being in when and where they are active. At the same time, flowering plants are also shifting their life cycles, blooming earlier or in different places. These shifts might seem small, but they have big consequences when flowers bloom, but bees are not there to pollinate them.

And the problem runs deeper. High temperatures can directly stress plants and pollinators. Fewer flowers appear, and those that do often produce less nectar. While a light haze can sometimes help plants by scattering sunlight more evenly, thick wildfire smoke does the opposite. With less light, photosynthesis slows, plants struggle, and nectar dries up. As a result, bees find less to feed on, visit fewer flowers, and grow weaker.

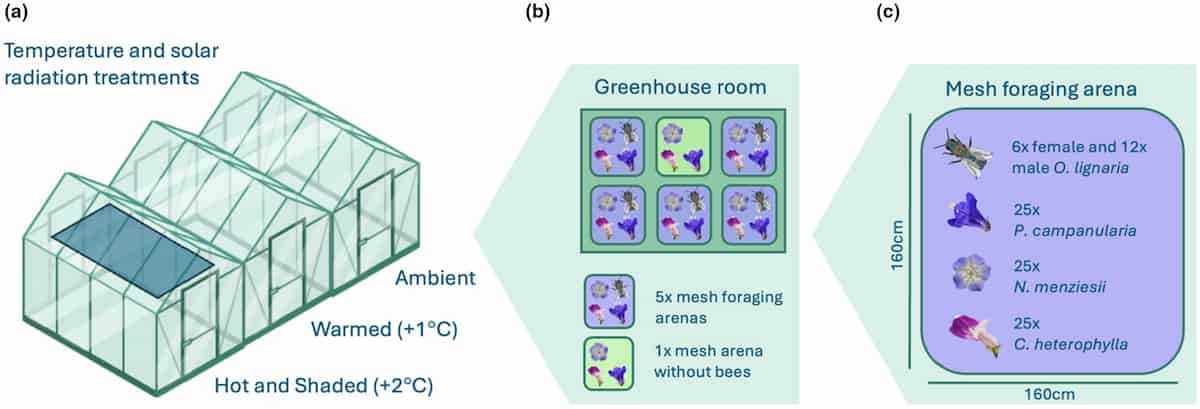

Previous studies have been working with these changes. However, they often looked at either warming or reduced sunlight in isolation. But what happens when both hit at once? Until recently, no one had the answer. So, Elena Kaminskaia and her team decided to find out. They created tiny artificial ecosystems inside greenhouses, mimicking three different climate conditions, to see how these changes affect bees, flowers, and the interactions between them.

They found that the combination of heat and heavy smoke-like conditions has negative effects on plant, bees and their interactions. In the “hot and shaded” condition, there were fewer flowers, and these produced nearly half as much nectar as those under normal conditions. Interestingly, the sugar content of the nectar did not change, but there was less available nectar. So, bees had to consume nectar from more flowers to fulfil their requirements.

Bee behaviour changed too. Under normal conditions, bees showed clear preferences, visiting specific plants. But under stress, they became less picky. They visited fewer flowers overall, but a broader variety of plant species. This means that they shifted from specialised to more generalist foraging behaviour. Additionally, they spent longer handling each bloom, likely because nectar was harder to find or more difficult to extract. While this flexibility might seem like a good survival strategy, it weakens pollination. When bees are less choosy, pollen is less likely to end up on the right flower, which reduces plant reproductive success over time.

Interestingly, even though fewer flowers were visited, seed production did not drop significantly in the short term. In fact, seeds produced under hot and smoky conditions germinated better than those from other conditions. The authors suggest that plants experiencing such harsh conditions and might prepare their offspring to sprout. Despite this, the long-term picture is less optimist.

These findings remind us that the future of pollination is not just about rising temperatures, but also about the increasingly smoky skies that come with more frequent and intense wildfires. When heat and haze combine, the relationship between plants and pollinators begins to falter. While in the short term, systems may compensate, over time the cumulative effects, such as fewer flowers, scattered nectar, altered bee behaviour, could erode interactions, especially for plants with specialist pollinators. More intense heat is expected under most climate change projections, and this is will likely push plants and pollinators beyond their comfort zones. And with smoke expected to be more frequent and prolonged in coming decades, the risks to pollination are only growing. Protecting pollination in a fire-prone world will mean understanding and responding to these complexes and overlapping pressures before resilience runs out.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Kaminskaia, E., Stuligross, C., & Rafferty, N. E. (2025). Pollination in a fire‐prone world: Reduced solar radiation and warming alter plant–pollinator interactions. Functional Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.70082

Victor H. D. Silva

Victor H. D. Silva is a biologist passionate about the processes that shape interactions between plants and pollinators. He is currently focused on understanding how urbanisation influences plant-pollinator interactions and how to make urban green areas more pollinator-friendly. For more information, follow him on ResearchGate as Victor H. D. Silva.