Natural history museums have long been powerful spaces for learning, with their vast collections drawing visitors from across the globe. Yet their gardens are often seen as pleasant extras rather than essential parts of the visitor experience. In a recent paper for Plants, People, Planet, Ed Baker and colleagues show how the grounds of the Natural History Museum in London have been transformed into a living display of evolution, climate action and the everyday choices people can make for nature.

In 2020, the Museum declared a “planetary emergency”, recognising the growing impact of human activity on the natural world. This sparked a rethink of how its indoor and outdoor spaces could better communicate the science of environmental change and encourage visitors to take meaningful action.

A major step in this vision has been the complete redesign of the Museum’s two hectares of gardens. The first area visitors encounter is the Evolution Garden, a time-travel walk through the history of life on Earth. It begins with some of the oldest rocks in the UK, formed during the Precambrian, and moves into a forest inspired by the Carboniferous period, when some of the planet’s first true woodlands appeared. Farther along, a full-size bronze Diplodocus stretches across a Jurassic-themed clearing of conifers, cycads and ferns. By the time visitors reach the Cretaceous plantings, the era when flowering plants evolved, the message is clear: evolution is not an abstract idea but a living, growing story that continues today.

The evolution theme continues at the Museum’s grand entrance, where planters showcase species from the Macaronesian islands of the Canaries, Madeira and the Azores. These striking plants, including Echium pininana and Sonchus canariensis, reveal how isolation on oceanic islands can produce giant, unfamiliar relatives of species found in the UK, turning the entrance into an unexpected lesson in how evolution shapes the world around us.

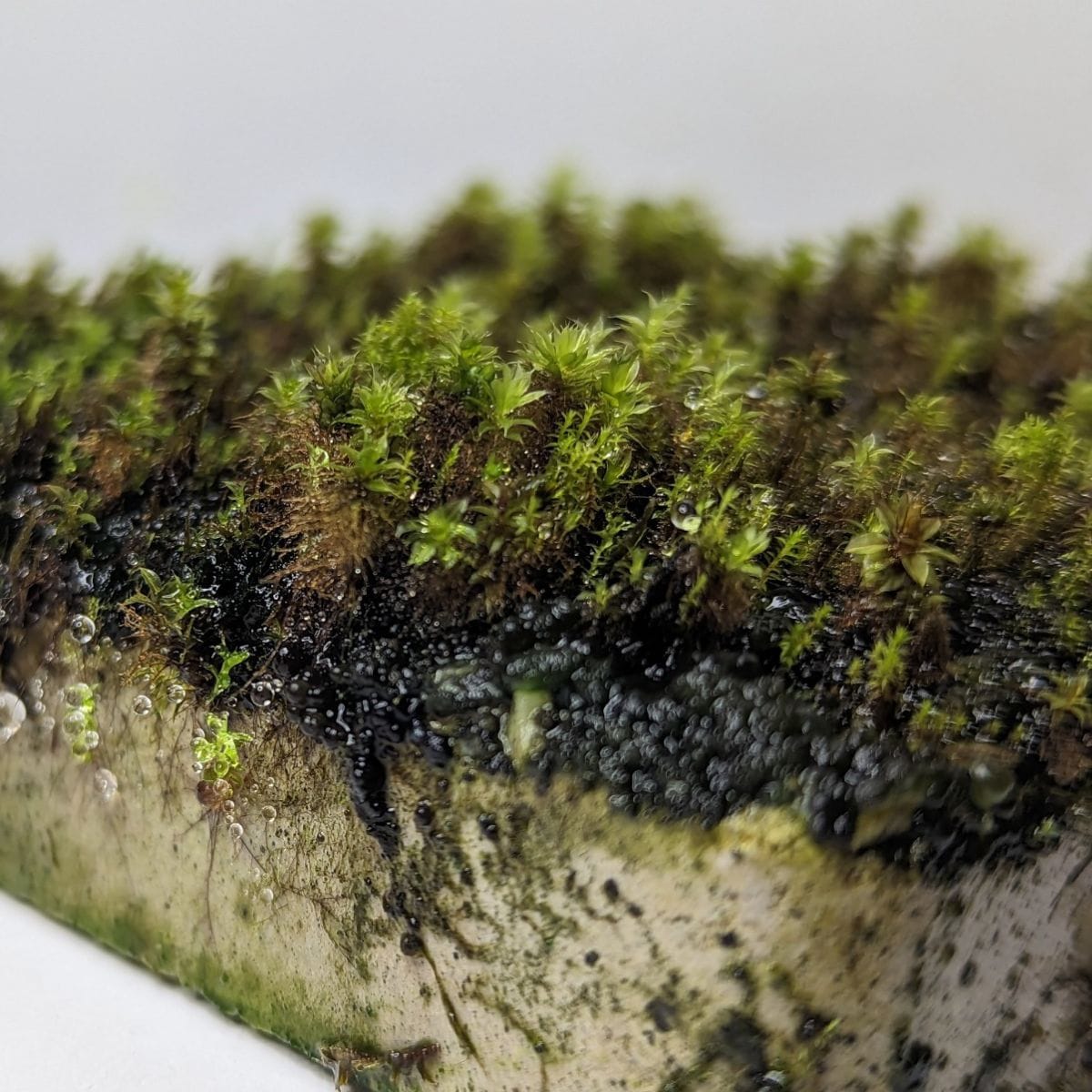

Moving west, the Nature Discovery Garden shifts the focus from deep time to today’s ecological challenges and to the small actions we can take to support the nature around us. It highlights the importance of urban wildlife and the need for ecological restoration through flower-rich grasslands, ponds and patches of native woodland. Many of these habitats are designed to be explored at eye level, giving visitors close encounters with the surprisingly rich biodiversity that thrives in this compact space.

This area also functions as both a research hub and a learning space. Scientists monitor how urban species establish and respond to shifting conditions, creating a long-term record that can guide future city planning. At the same time, school groups use the garden as an open-air laboratory, learning to identify insects, test water quality and practise hands-on ecological monitoring. In doing so, the Museum has turned this space from a decorative border into a place where science is not only observed, but lived.

Taken together, the redesigned gardens show how outdoor museum spaces can become places of genuine discovery rather than mere backdrops to the indoor collections. Because they are built on plants, the foundation of most terrestrial ecosystems, they can act as living collections that reveal how nature works, how it has changed through time and how it continues to respond to human pressures.

Early visitor numbers suggest that this new approach is already making an impact. More than 84% of surveyed visitors felt the gardens clearly communicated themes such as plant evolution and the relationship between plants and their environment. Millions now use the space not just as a pathway to the galleries but as a destination in its own right. For many, it is their first close encounter with native plants and urban wildlife. Remarkably, over 90% said they wanted to spend more time in natural spaces after their visit, and more than 76% felt inspired to take action to support nature in their communities.

The project also tackles a broader issue: access to nature in cities is both limited and uneven. By offering a free, central green space that blends beauty, learning and research, the Museum provides an inclusive place where people can reconnect with the living world. The results point to a wider truth running through the study: people protect what they experience and understand. The Natural History Museum’s work shows how cultural institutions can reimagine their outdoor spaces to support richer biodiversity and help spark the environmental action our cities urgently need.

READ THE ARTICLE

Baker, E., Kenrick, P., Knapp, S., McCarter, T., & Tweddle, J. (2025). Catalysts for change: Museum gardens in a planetary emergency. Plants, People, Planet. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.70100.

Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz

Erika is a Colombian biologist and ecologist passionate about tropical forests, primates, and science communication. She holds a Master’s degree in Ecology and Wildlife Conservation from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and has been part of Ciencia Tropical since 2020—a science communication group that aims to connect people with biodiversity and raise environmental awareness. You can follow her and her team on Instagram at @cienciatropical.Spanish and Portuguese translation by Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz.