Concrete generally evokes something bare, grey, and lifeless. Yet a new study from Delft University of Technology poses a provocative question: what if concrete could host a living, self-sustaining moss layer, transforming walls and infrastructure into thin “green carpets” that cool cities, dampen sound, and filter the air? Rather than waiting for years for natural colonization or relying on costly irrigated green walls, the authors propose a pragmatic middle ground: design concrete to be bioreceptive, grow moss rapidly indoors, and then make it drought-resistant before taking it to the outdoor environment.

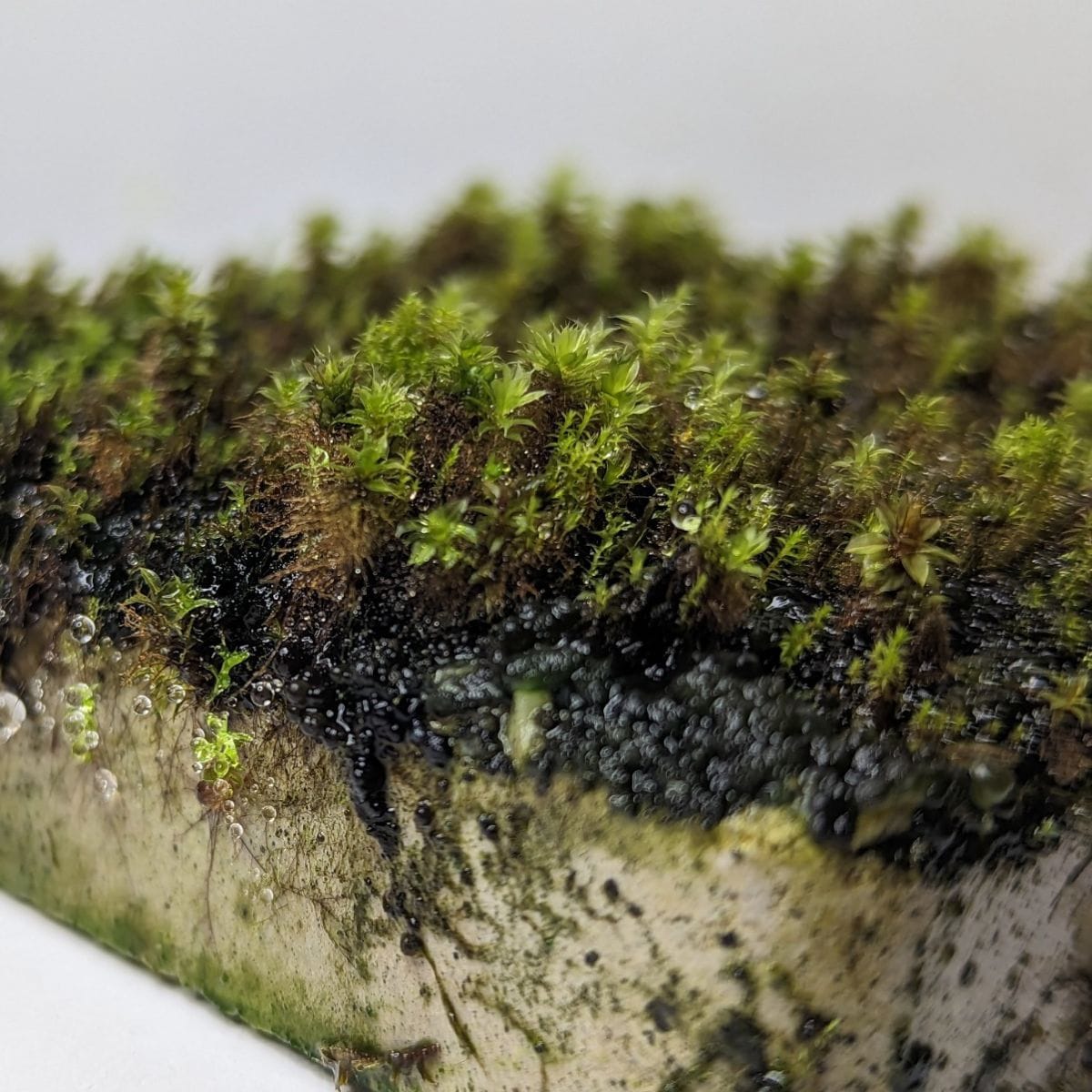

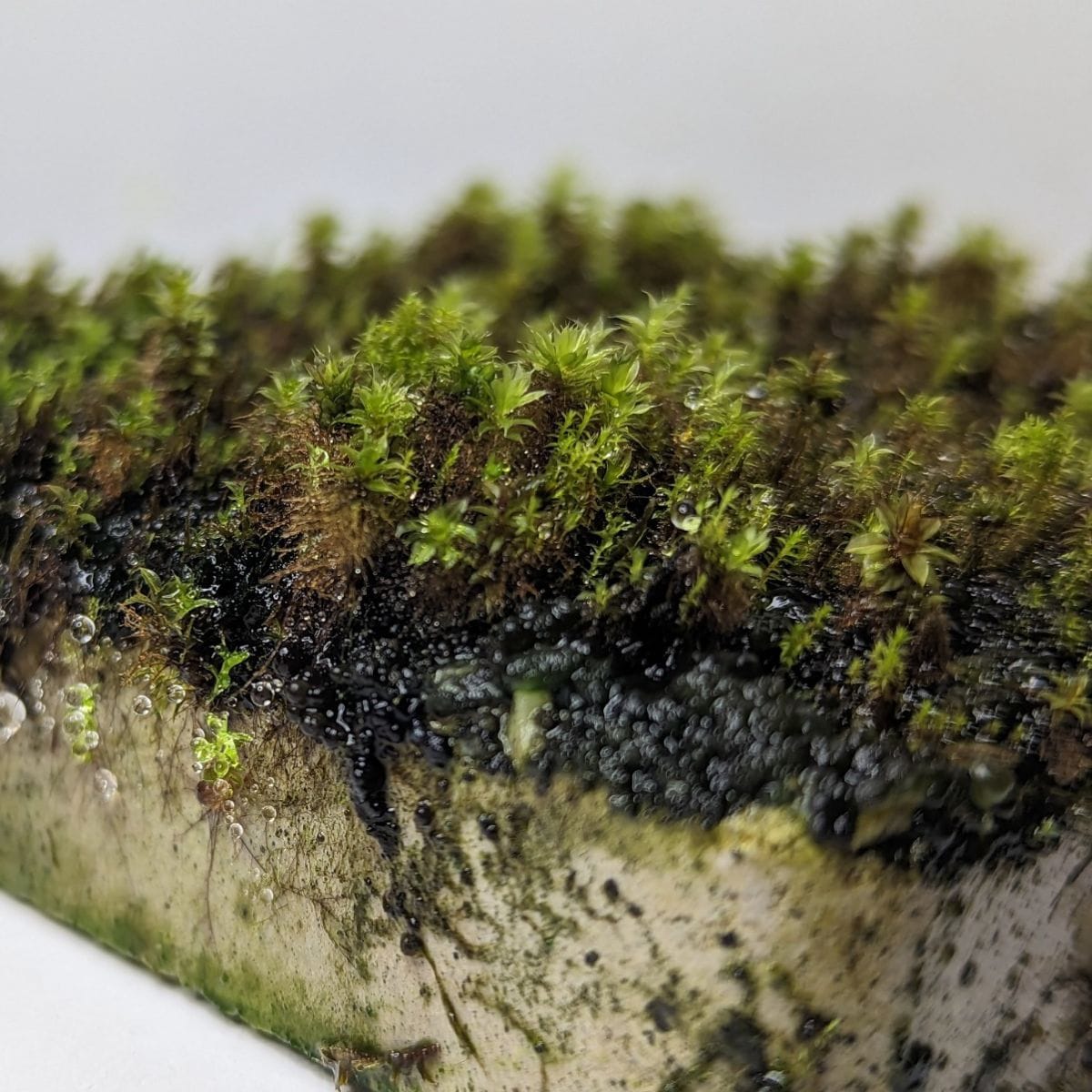

To achieve this, Max Veeger and collaborators developed a two-step protocol to cultivate moss on bioreceptive concrete and keep it alive outdoors. In the first step, they focused on rapid establishment indoors: they tested twelve growth regimes combining different irrigation frequencies, light intensities, and “hardening” treatments (increasing resistance to environmental stresses, such as light and water deficit) for two moss growth forms, mixtures of acrocarp and pleurocarp species. The winning recipe was surprisingly simple: keep the moss under relatively low light, water it daily for the first six weeks, and then gradually reduce irrigation to once every four days, inducing drought tolerance without sacrificing coverage and layer thickness. Under these conditions, pleurocarp mixtures achieved over 50% green coverage and moss carpets around 15–16 mm after 12 weeks, while acrocarps formed thinner carpets, yet still substantial.

The second step tested whether these moss communities, grown indoors, could cope with the real world. Mixtures and individual moss species, such as Tortula muralis, Ptychostomum capillare, and Brachythecium rutabulum, were cultivated indoors using the best growth regime and then transferred to outdoor structures in a botanical garden, facing either north (greater shading) or south (greater solar exposure). For the first three months outdoors, all samples were covered with a mesh blocking 50% of light to reduce UV radiation and high irradiance shock. After 15 months, chlorophyll fluorescence values, a measurement of photosynthetic activity, were comparable to those of mosses in natural environments, showing that the photosynthetic machinery remained functional even after losing part of the visible coverage during the transition from indoor to outdoor environment.

Not all mosses behaved the same way. The slower-growing yet resilient acrocarp Tortula muralis emerged as the most reliable species, maintaining the highest surface coverage on concrete surfaces facing both north and south, albeit with relatively thin carpets. Pleurocarp species such as Brachythecium rutabulum and mixtures containing pleurocarps grew rapidly and thickly indoors, but outdoors they struggled to remain adhered, particularly on south-facing surfaces, where layer thickness and coverage dropped sharply, partly due to higher wind incidence and strong mechanical pressure on the carpets. The authors suggest this poor adhesion may be linked to weak rhizoid development under very wet indoor conditions and point to possible solutions, such as the use of exogenous auxin, adhesive agents or biodegradable glues, alongside carefully planned species mixtures to improve anchorage.

Behind these technical details lies a broader vision. Mosses are poikilohydric, meaning that they don’t retain water the way vascular plants do and so have evolved to handle difficult water suplies, tolerate desiccation, and require no permanent irrigation systems, making them particularly suited to greener cities where water, space, and maintenance budgets are limited. Bioreceptive concrete colonised by moss can offer many of the same benefits as green walls: thermal and acoustic insulation, particle retention, and aesthetic softening of hard surfaces, at lower construction and maintenance costs. This study does not provide a final recipe for all species or climates, but offers a viable protocol and a clear message: if we want our cities to harbour life rather than repel it, we must consider materials, species selection, and growth regimes simultaneously from the start, bringing nature to “our concrete jungles”.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Veeger, M., Ottelé, M., & Jonkers, H. M. (2026). Growing moss on bioreceptive concrete using a novel two-step approach: The effects of light, water, and species selection. Ecological Engineering, 223, 107839.

Pablo O. Santos

Pablo is a PhD student in Plant Biology at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Brazil), where he conducts research on photoprotective strategies and antioxidant potential of bryophytes from ferruginous outcrops. His research interests lie at the intersection of physiology, ecology, and phytochemistry of bryophytes, with an emphasis on the ecological role and biotechnological applications of liverworts, mosses, and hornworts.

Portuguese Translation by Pablo O. Santos.

Cover picture by Max Veeger.