Most people know Charles Darwin for his renowned book On the Origin of Species, a work that revolutionised our understanding of life on Earth. But if asked which organisms he studied, what would come to mind? For many, the answer begins and ends with Darwin’s famous finches or other emblematic Galápagos fauna. If that’s your answer too, you are not alone.

A recent study by Martí Domínguez and Dr Tatiana Pina, published in Science & Education, shows that while Darwin is often celebrated for his work on animals, his botanical research remains largely overlooked. The team surveyed over 500 visitors to Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum —the oldest living collection of trees in the United States— about Darwin’s life and work and their understanding of evolution.

The findings were clear: while most visitors recognised Darwin and over 80% knew he had worked with animals, less than half knew he had worked with plants. This bias became more evident when researchers asked about specific species, with almost every visitor mentioning the famous Galápagos finches but far fewer able to name a single plant species. Those who did mentioned orchids, one of Darwin’s best-known botanical subjects.

People’s knowledge about evolution also showed a clear bias towards animals. Respondents mentioned several examples of animal evolution, including the evolution of humans from a common ancestor shared with apes, and transitions from dinosaurs to birds, and from wolves to dogs. In contrast, plant examples were largely limited to adaptations, such as thorns or toxins, or species adapted to particular environments, like cacti in deserts. As a result, the authors argue that respondents struggled to see the bigger picture of how plant species evolved over time.

While On the Origin of Species and his studies on animals are undoubtedly important, plants were central to how Darwin developed and tested his theory of natural selection. In fact, six of his fifteen major works focused entirely on plants, from the intricate pollination strategies of orchids to the predatory habits of carnivorous plants. Moreover, during his visit to the Galápagos, Darwin showed great interest in the island flora, long before the finches captured his attention. Yet Darwin’s plant studies have long been overshadowed, and Domínguez and Pina suggest this imbalance may arise from the way evolution is taught and presented. School textbooks and museum exhibits often spotlight animal lineages, such as humans, birds, and whales, while plant evolution rarely gets a mention.

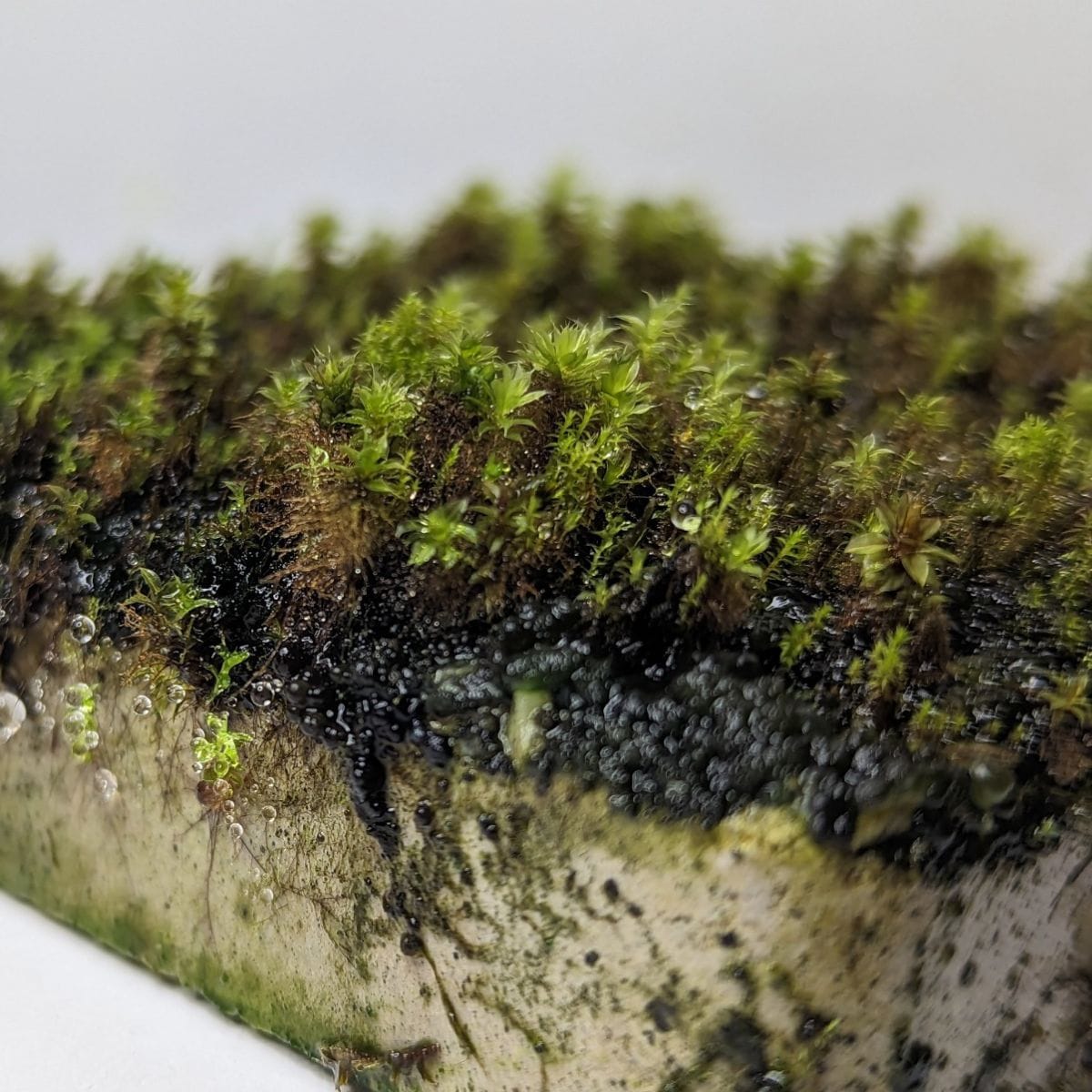

The authors point out that botanical gardens could help change that. These spaces are not only beautiful; they are also living laboratories, home to conservation projects and public education. Like natural history museums, they offer opportunities for informal learning, but with living collections that make evolution tangible. Past exhibitions, such as “Darwin’s Garden” at the New York Botanical Garden, have shown how plants can tell compelling evolutionary stories. Notably, about 70% of respondents in Domínguez and Pina’s survey thought botanical gardens should actively teach about plant evolution. For example, they suggested adding interpretive signs, guided tours, special exhibitions, or even prehistoric plant displays.

This study makes it clear that Darwin’s botanical works and the broader story of plant evolution, remain largely untold to the public. By focusing on animals, we risk leaving out half the picture of how life on Earth has changed and adapted over time. Botanical gardens are perfectly placed to showcase plant evolution, inviting visitors to see plants not as static green scenery but as dynamic players in the history of life. Next time you walk through a botanical garden, look closer: the story of evolution isn’t only sung by birds —it’s written in leaves, petals, and seeds. Darwin knew it, and it’s time we did too.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Domínguez, M., & Pina, T. (2025). Did Darwin Work with Plants? Darwinism, Evolution and Education in a Botanical Garden. Science & Education, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-025-00670-z

Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz

Erika is a Colombian biologist and ecologist passionate about tropical forests, primates, and science communication. She holds a Master’s degree in Ecology and Wildlife Conservation from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and has been part of Ciencia Tropical since 2020—a science communication group that aims to connect people with biodiversity and raise environmental awareness. You can follow her and her team on Instagram at @cienciatropical.

Spanish and Portuguese translation by Erika Alejandra Chaves-Diaz.

Cover picture by Elliot & Fry (Wikimedia Commons).