Imagine walking down a busy street in your city. Among the buildings, cars, and concrete, you might think nature has disappeared. But if you look closely at the ground, you may spot tiny plants growing in cracks in the pavement, or colourful flowers blooming beside a fence. These little signs show us that even in the city, life finds a way to thrive.

For a long time, scientists believed that as cities grow, they lose their natural diversity. Cities tend to favour only a small group of generalist species that can survive almost anywhere. Because of this, different cities would end up sharing the same types of plants. The idea here is that a community garden in your own city would eventually present plant diversity very similar to those in Berlin, Munich, New York or São Paulo. This idea is known as the Urban Biotic Homogenisation hypothesis.

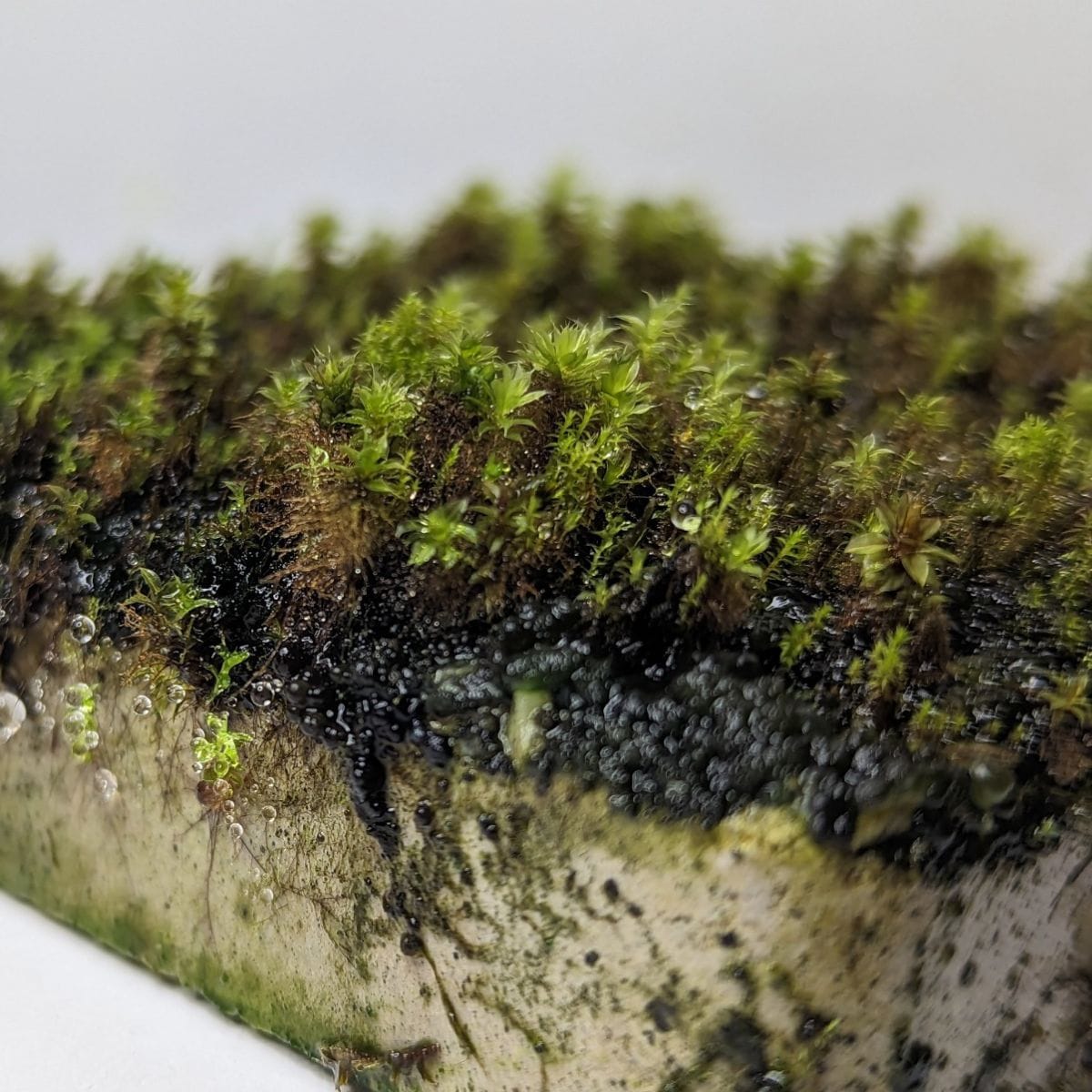

However, the truth turns out to be more surprising. Cities contain forgotten corners and small gardens where nature is far richer than we might imagine. Community gardens are special places where cultivated plants live alongside wild plants that appear naturally, creating a unique patchwork of life in every space.

With this in mind, Aaron N. Sexton and his team set out to find out if urban gardens are really similar in species as cities grow. They studied more than 30 gardens across two German cities (Berlin and Munich) over four years, observing how plants organise themselves in these special urban oases.

The researchers found that gardens in Berlin and Munich were quite different, especially regarding wild plants. Even more unexpectedly, wild plants grew more diverse in gardens located in highly urban areas, contradicting the long-held belief that cities make nature more uniform. Wild plants stole the spotlight, explaining most of the variation in plant life across the gardens. This highlights how important spontaneous nature is for keeping city gardens alive and varied.

This difference arises from each city’s unique history and planning. Berlin’s patchwork of abandoned lots, railway edges and remnant natural habitats encourages a wider variety of wild plants. Munich, on the other hand, with its more manicured and continuous green spaces, supports fewer species. In other words, the historical context in which these gardens were created, along with how they are managed, really matters.

Similarly, who tends the garden matters too. Gardeners shape these urban plant communities through their decisions about weeding, planting and simply allowing nature to take its course. The study showed that cultivated plants, like tomatoes and beans, were more similar between the two cities but still not identical.

These findings offer a hopeful message for cities worldwide. Urban gardens are not just spaces to grow food. They are vibrant, living ecosystems shaped by a blend of human care and wild resilience, boosting biodiversity across the urban landscape. Furthermore, the study suggests it is time to rethink old ideas about urbanisation leading to ecological sameness. Instead, we should recognise the value of overlooked places, such as community gardens, which support rare and diverse species.

As cities keep expanding, we need to pay closer attention to how everyday places can become hotspots for biodiversity. With careful management, support for native and wild plants and greater awareness of their importance, urban gardens could become key players in creating richer, more adaptable cities for both people and the nature that lives among them.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Sexton, A. N., Conitz, F., Sturm, U., & Egerer, M. (2025). Wild Plants Drive Biotic Differentiation Across Urban Gardens. Ecology and Evolution, 15(6), e71527. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.71527

Victor H. D. Silva

Victor H. D. Silva is a biologist passionate about the processes that shape interactions between plants and pollinators. He is currently focused on understanding how urbanisation influences plant-pollinator interactions and how to make urban green areas more pollinator-friendly. For more information, follow him on ResearchGate as Victor H. D. Silva