Millions of years ago, our planet was dominated by reptiles that inhabited the seas, the skies and the land. Among them were the dinosaurs, massive animals that have intensely occupied our imagination since the advent of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park. Studying these animals seems to be an impossible task when you don’t have a time machine, like those from science fiction books and films. However, during the last centuries, paleontologists have explored the past using fossils, which act as records of the old times and provide information about Earth’s history and its biodiversity.

Several of these dinosaur species were giant herbivores that ate enormous amounts of plants, yet somehow managed to live together in the same sites. Given their size, diversity, abundance, and basic needs, how could these animals coexist for millions of years?

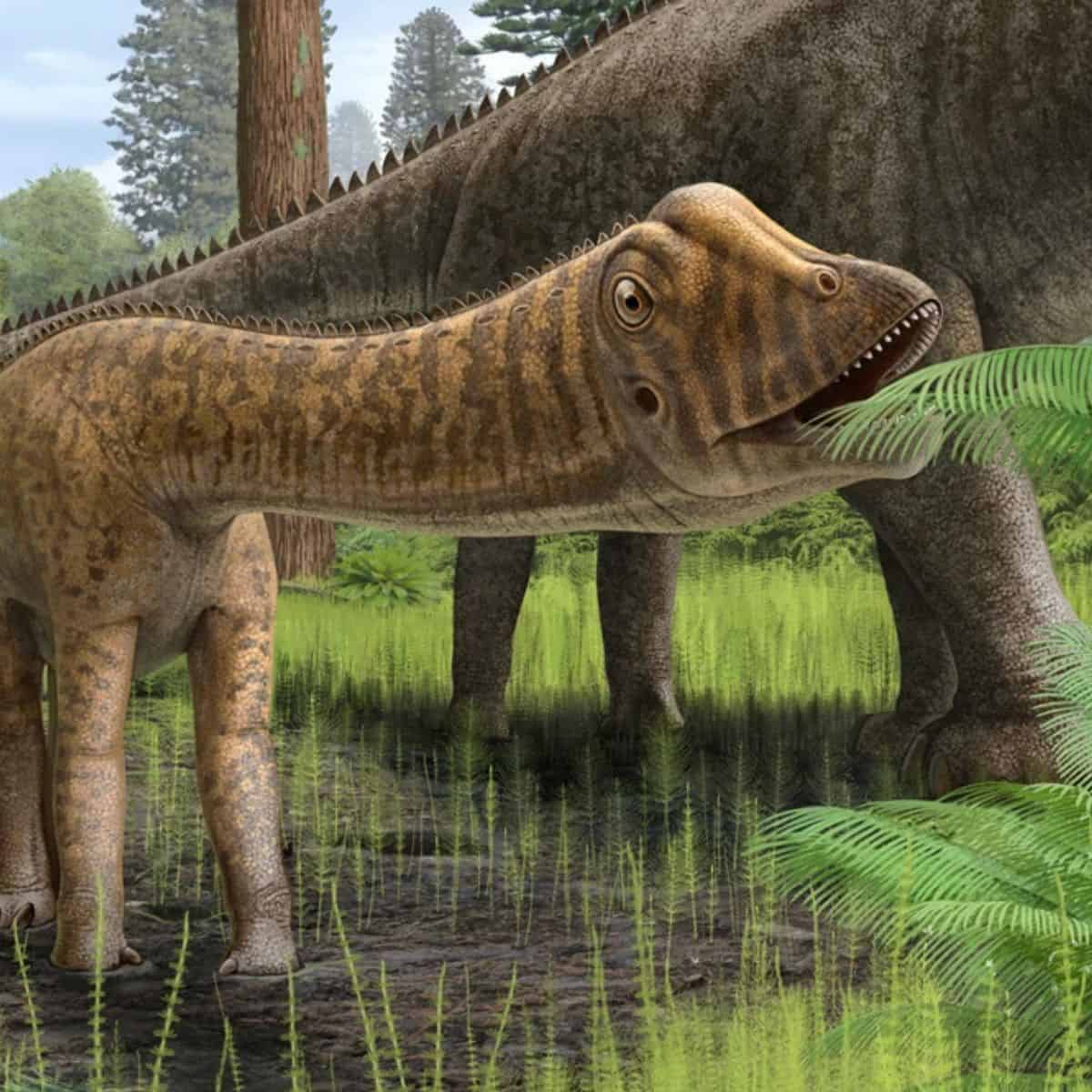

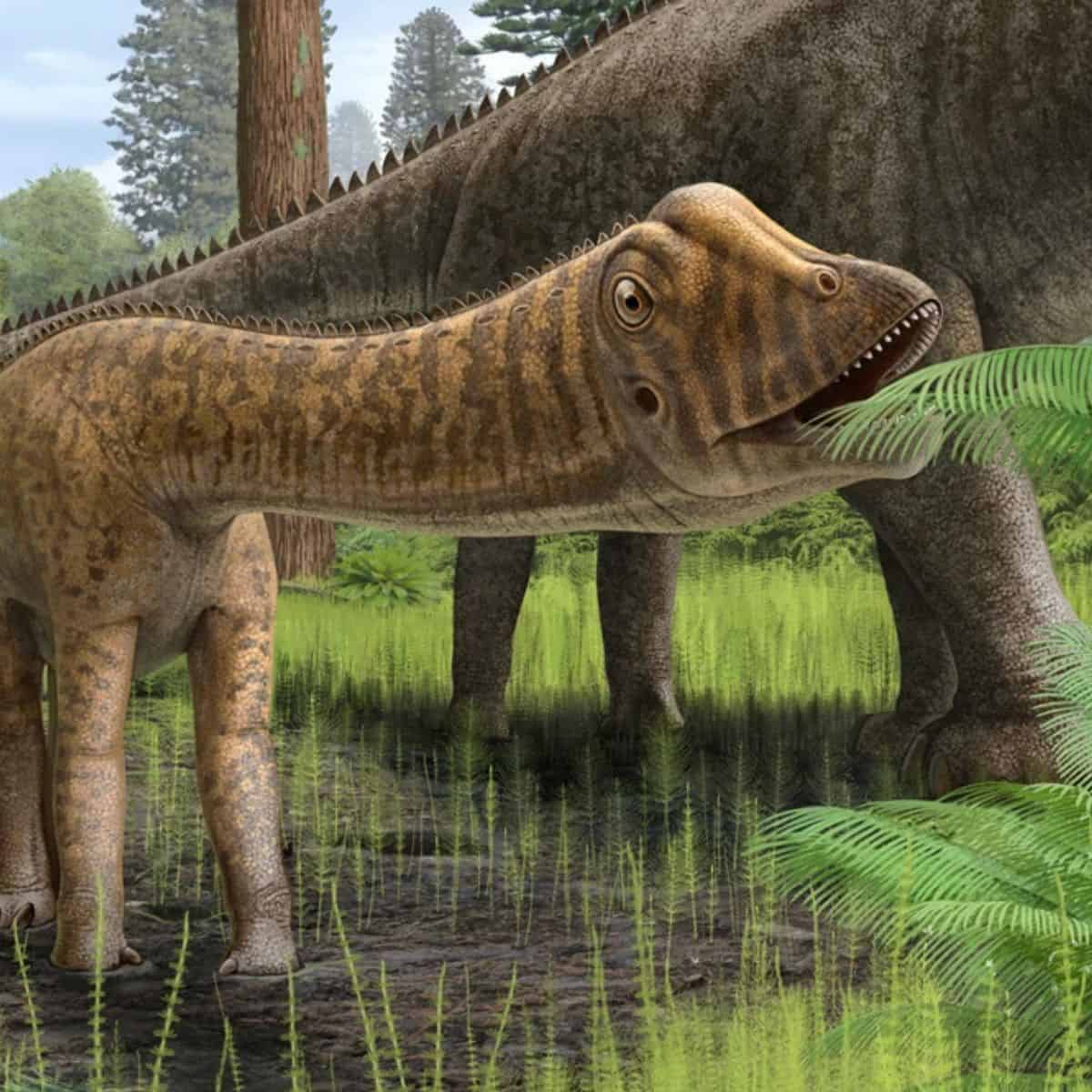

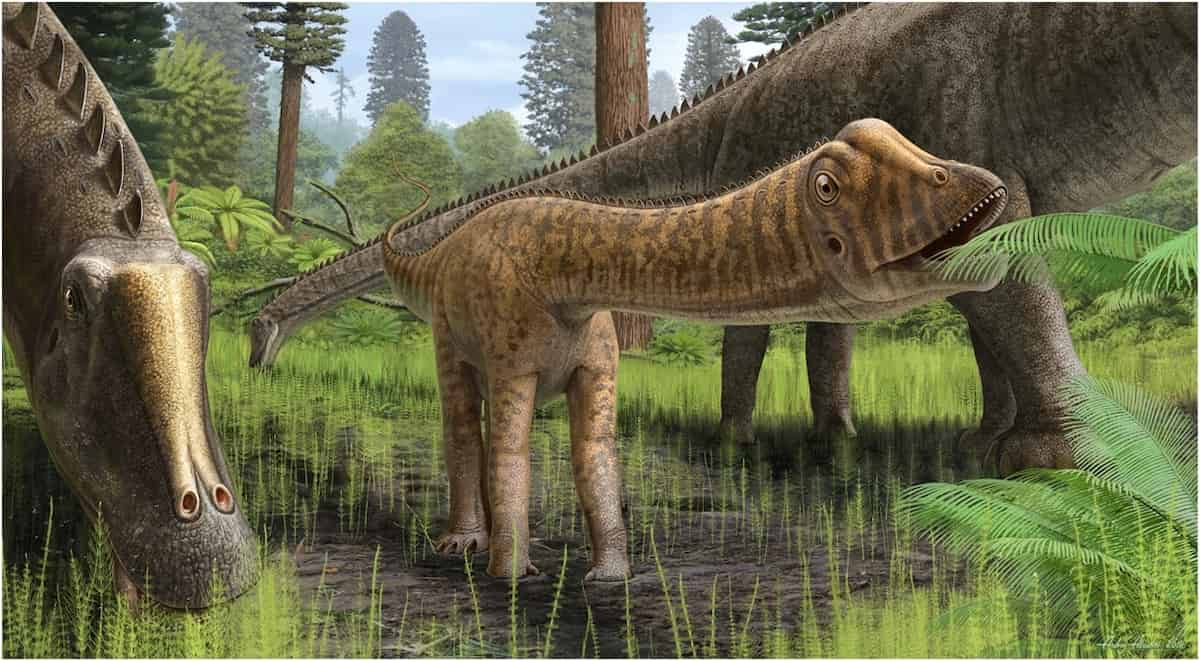

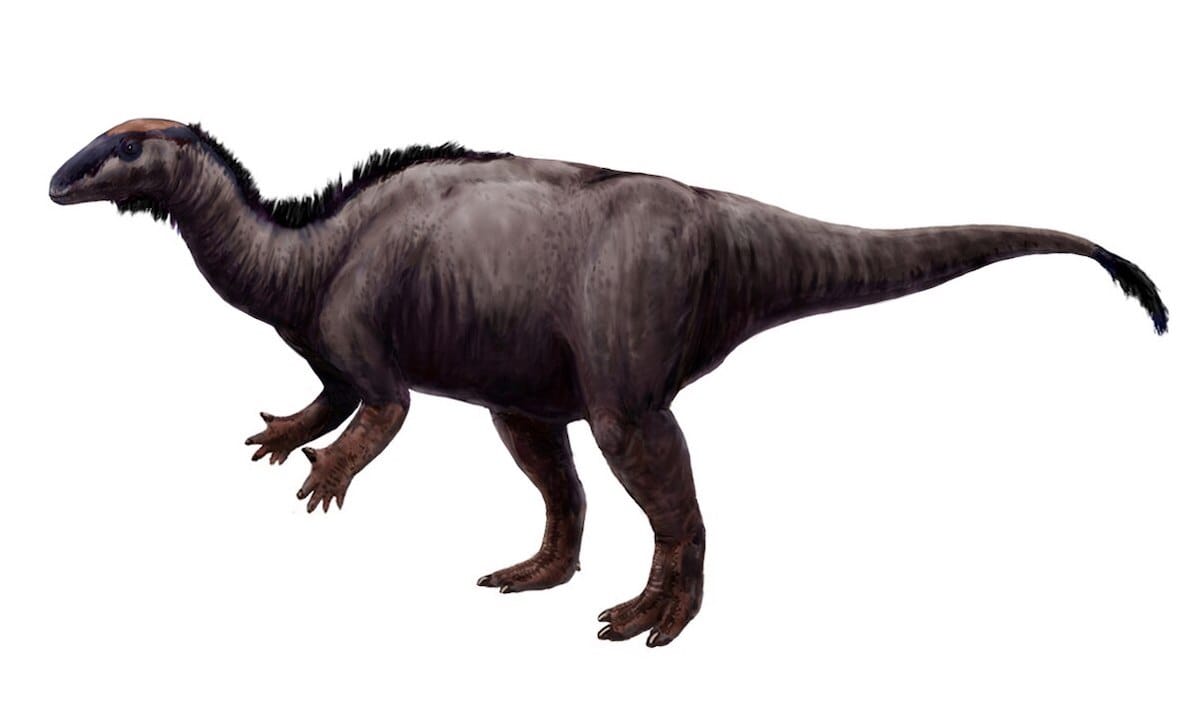

The answers to this enigma emerged from studies such as the recent research by Liam Norris and colleagues, where they analysed the structure of a dinosaur community whose fossils were collected at the Carnegie Quarry (Utah, United States), which spans about 7 million years of the Late Jurassic period. This place tells the story of an ancient and thriving ecosystem, home to gigantic herbivores such as Camarasaurus (15-20 meters long), Camptosaurus (5-7 meters long) and Diplodocus (24-26 meters long). The coexistence of these animals is quite intriguing to scientists, which motivated Norris and his partners to analyse possible differences in the feeding habits of different herbivores that would explain how they managed to inhabit the same ecosystem.

To reconstruct the diets of the chosen animals, the researchers measured the ratio between two calcium isotopes in the teeth of three herbivore dinosaurs and some carnivore animals (theropod dinosaurs and relatives of modern crocodiles). Isotopes are different types of atoms of the same chemical element that have different numbers of neutrons. In the case of this research, Norris’ team focused on two forms of calcium, the most frequent one known as 40Ca and 44Ca, which has four additional neutrons. Since calcium is well-preserved in fossils and is obtained solely through the animal’s diet, knowing the ratio of these calcium forms in dinosaurs bones can give us a hint on the kind of food they consumed. For example, soft plant tissues, such as leaves, tend to store more 44Ca, so animals that feed heavily on these tissues accumulate more of this isotope, resulting in a higher 44Ca/40Ca ratio in their bones.

Through the data obtained, the authors found not only the expected variations between the diets of carnivores and herbivores, but also between the herbivores themselves, proving their hypothesis. Carnivores presented lower calcium isotope ratio values than herbivores. Camarasaurus and Camptosaurus had different feeding habits, consistent with their sizes and the height they likely reached to feed. The shorter Camptosaurus fed on soft vegetal structures like leaves and buds, while the taller Camarasaurus had a mixed diet, feeding more on woody tissues, such as branches. However, height wasn’t enough to explain these differences, as the even taller Diplodocus presented intermediate isotope ratio values. This could be due to its feeding habits as a low browser, mostly consuming ferns or horsetails. As a result, while Camptosaurus and Camarasaurus likely didn’t compete for the same food sources, Diplodocus might have competed with these both for similar plant parts.

Previous studies suggested that differences in herbivore feeding habits were directly linked to the dinosaur height, as it would offer access to different plant parts. However, Norris and his team found that height alone didn’t explain the variations in isotope ratios. For example, Diplodocus, the tallest herbivore assessed, had isotope ratios similar to those of both the shorter Camptosaurus and the also tall Camarasaurus. Instead, the separation of food niches is more closely related to the type of plant component consumed.

These massive results reveal a new chapter of the dinosaurs tale. Norris’ research shows us the importance of singular structures like fossilized teeth to reconstruct the tapestry of Earths’ history and to get a large amount of paleontological information. Throughout the evolution process, those hungry herbivore titans found a way to coexist feeding on different resources and thriving in the same ancient environment for millions of years.

Norris, L.; Martindale, R.C.; Satkoski, A.; Lassiter, J.C.; Fricke, H. (2025) Calcium isotopes reveal niche partitioning within the dinosaur fauna of the Carnegie Quarry, Morrison Formation. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 675, p. 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2025.113103

Gustavo Macêdo do Carmo

Gustavo (he/him) is a Brazilian paleontologist and parasitologist currently doing his PhD at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Belo Horizonte, Brazil) and working on trace fossils, ancient parasitic infections and integrative taxonomy of extant parasitic worms. You can find more information about him at linktr.ee/gustasmo.