Since ancestral times, humans had shown deep emotional and cultural connection with beautiful, colourful, and smellful floral structures. But … What makes a flower? This Botanical Pill addresses this fascinating question by briefly introducing the ABC of flower development and presenting recent insights into the real functions of specific floral organs.

Archaeological evidence revealed that early humans used flowers in their rituals and glorious civilizations of the past adopted floral patterns in their decorations. For millennia, flowers have also been appreciated for their pharmaceutical properties, as reported in ancient recipes of traditional medicine in China or ayurvedic practices in India. Still today, flowers are always present in spiritual practices and religious ceremonies to celebrate essential life events, from birth to funerals.

BUT DO WE REALLY KNOW WHAT IS A FLOWER?

The flower is a key innovation that first appeared 100-150 Million Years Ago (MYA) in higher plants of the angiosperm lineage (Botanical Pill “The evolution of land plants”). Their sudden origin and rapid diversification on planet Earth have puzzled scientists since the early theories on evolution: Sir Charles Darwin coined the term “the abominable mystery” for flowering plants since he considered them an exception to the gradual evolution of organisms (“natura non facit saltum”) due to lack of evidence of intermediate species between gymnosperms and angiosperms.

Can scientists solve Darwin’s ‘abominable mystery’ about the angiosperm explosion? – YouTube

Strikingly, the development of complex floral structures turned out to be essential for successful sexual reproduction that contributed to the explosion of the most diverse group of land plants, which currently constitutes almost 90% of the terrestrial flora.

The ABC of FLOWER FORMATION

Flowers are specialized plant structures composed of four main organs, each playing a specific function, that develop in concentric rings called whorls. Despite the great diversity of floral structures existing in nature, the architecture of flowers is well conserved among different species: all floral organs originate from the floral meristem (i.e., a pool of pluripotent cells of the shoot apex that differentiates reproductive units) following a similar organization. 50 years of research on the molecular basis of flower development revealed that the formation of floral structures is under strict genetic control: specific genes – called floral homeotic genes – are switched on/off in the floral meristem following precise spatial and temporal patterns, thus transforming undifferentiated cells into specialized sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils. But how?

For decades, plant scientists have studied mutants of the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana (Botanical Pill ”The botanist’s lab rat”) that showed the conversion of one floral organ into another (i.e., floral homeotic transformations) and discovered that these “weird flowers” were caused by mutations in regulatory genes that determine the identity of different floral organs (details in Flower development).

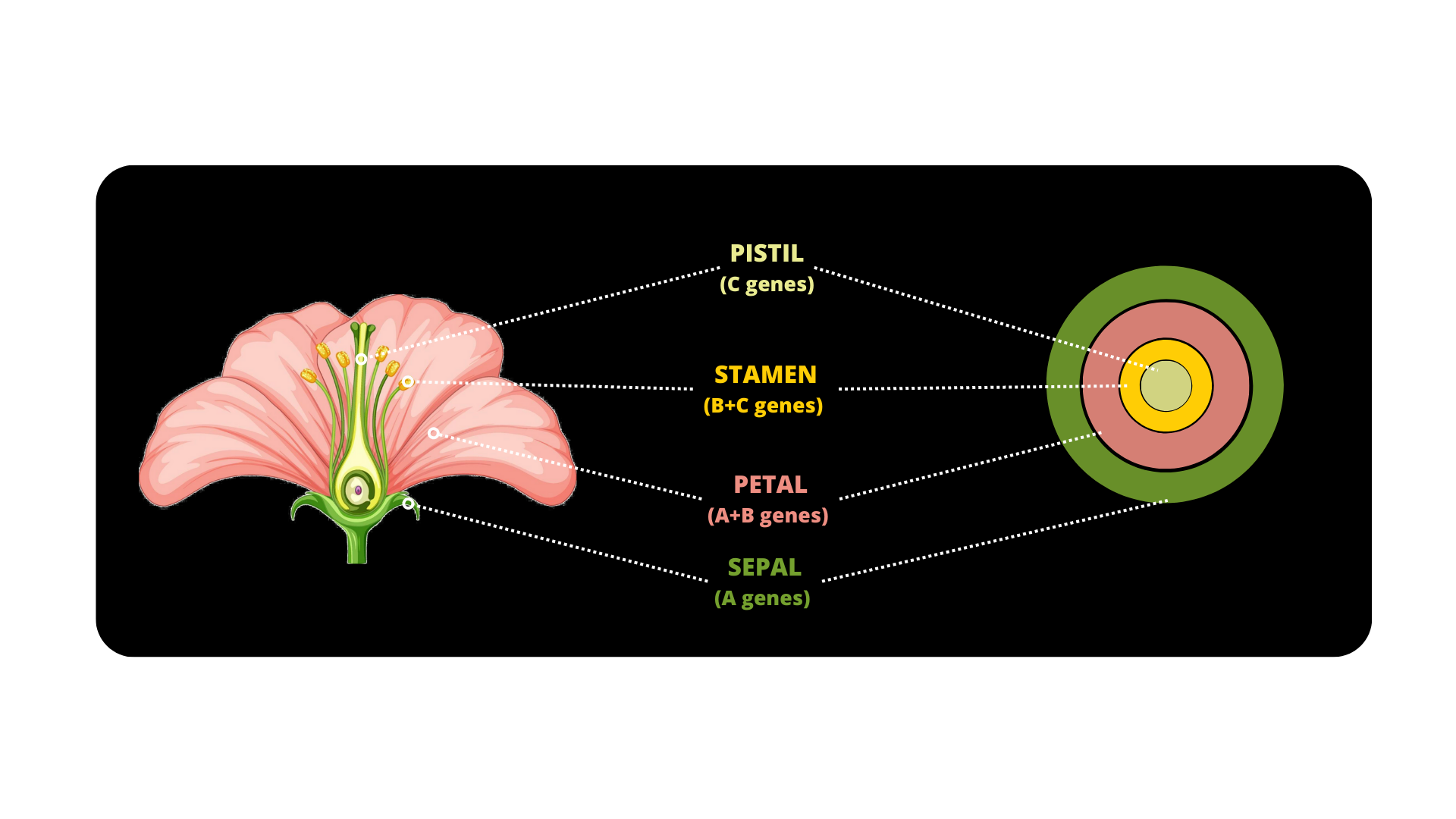

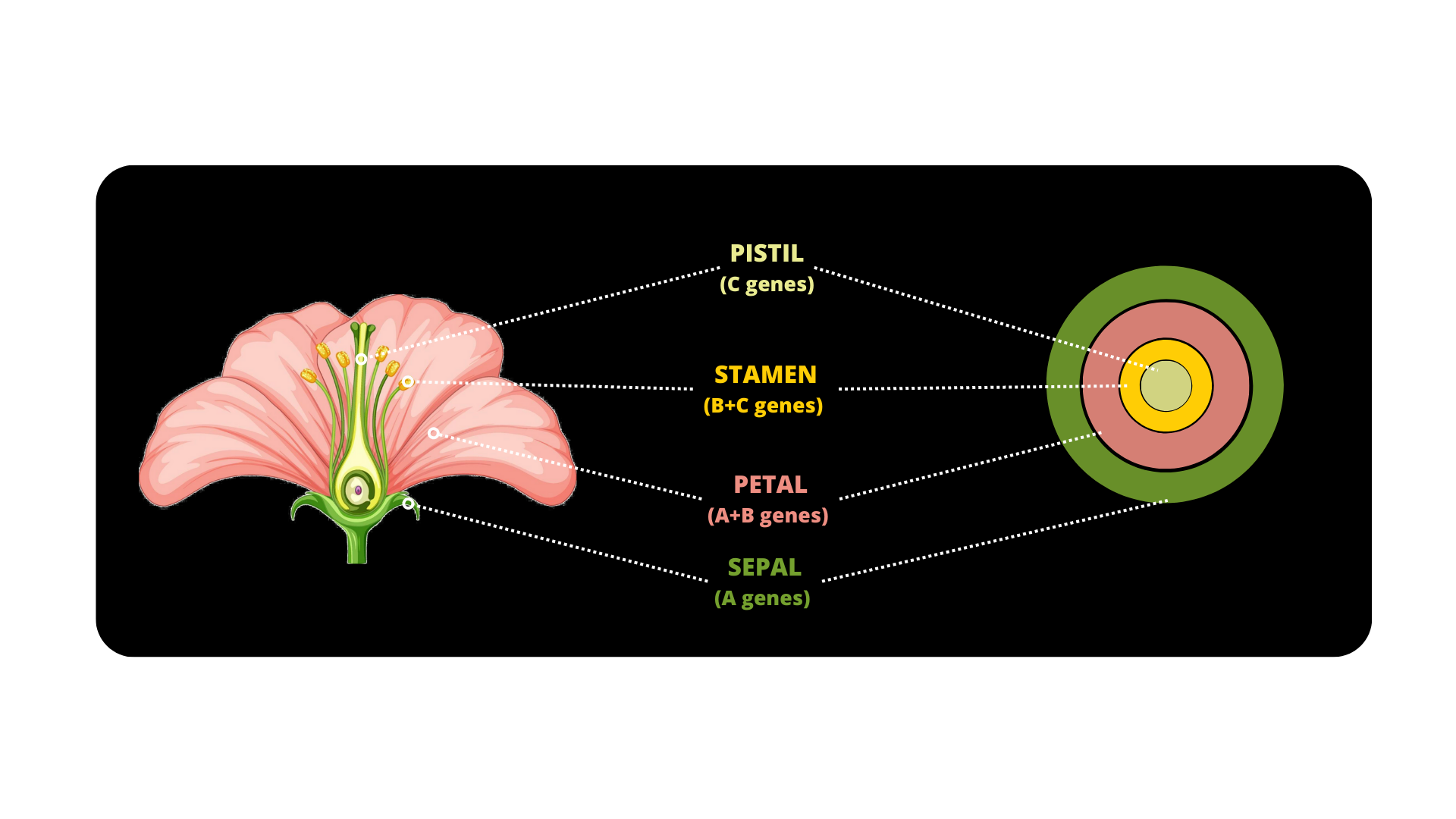

In the 1990s, researchers Enrico S. Coen and Elliot M. Meyerowitz proposed a simple ABC model to explain the complex processes underlying the formation of the flower (Figure 1): class A genes are active in outer whorls to specify sepals and petals; class B genes are active in intermediate whorls to specify petals and stamens; and class C genes are active in inner whorls to specify stamens and pistils.

Since then, independent groups worldwide have used a wide range of molecular techniques and Next Generation Sequencing to decipher the complex network of genes that regulate flower development, and discovered that key regulatory factors act and interact in different whorls to turn on/off thousands of target genes that make up a specific floral organ.

VARIATIONS IN FLOWERING (AND NON-FLOWERING) PLANTS

Although the great majority of angiosperms form perfect flower (i.e., hermaphrodite flowers with both male and female reproductive organs), a smaller percentage form staminate flower (lacking pistils) or pistillate flowers (lacking stamens).

Strikingly, several amazing garden plants have been selected over time for unusual modifications in their floral organs (Figure 2), ultimately caused by alterations in the expression pattern of ABC genes.

Intriguingly, some floral homeotic genes are also expressed in species belonging to the the Gymnosperm lineage, non-flowering plants that produce male or female cones (but not flowers). These seed plants lack A genes but express B genes in male reproductive organs and C genes in both male and female structures (or cones). Other land plants that appeared early in the evolution, such as Bryophytes (e.g., Physcomitrium) and Lycophytes (e.g., Selaginella), completely lack ABC genes and do not form floral organs.

THE SEXUAL LIFE OF FLOWERING PLANTS

Sexual reproduction takes place though self-pollination (i.e., the fusion of male and female gametes produced by individual plants) in autogamous species, but through cross-pollination (i.e., the fusion of male and female gametes produced by different plants) in allogamous species (Figure 3). In the latter plant category, this process is facilitated by vectors that transfer pollen from one plant to another one (of the same or compatible species). Therefore, the famous quote “There were three of us in this marriage, so it was a bit crowded” can be easily applied to allogamous species! The ‘third component’ can be a natural element – including gravity, wind, and water – or another living organism – such as insects, birds, mammals, or even humans (just think about Gregor Mendel crossing different pea plants in his garden!).

THE REAL FUNCTION OF GORGEOUS FLOWERS

Flowering plants have developed smart strategies to attract visiting animals, thus ensuring their reproductive success. Petal colour and floral scent are among the most studies floral traits that impact flower attractiveness for animal pollinators, as reported in a special issue of the scientific journal Physiologia plantarum.

The endless possibilities of floral colour palette rely on the combination of only 4 types of pigments – chlorophylls (green), carotenoids (yellow-orange), anthocyanins (orange-magenta-blue) and betalains (yellow-red) – that also play essential roles in photosynthesis, UV protection and stress response.

The colour of a flower is the result of complex biological processes, controlled at the molecular and biochemical levels. Indeed, regulatory factors modulate the activity of specialized metabolic enzymes that produce pigments in petals. For example, Arabidopsis B-class factors switch off “photosynthetic genes” in the second whorl of developing flowers, resulting in white petals. In addition, variation at genes encoding regulatory factors and/or components of biosynthetic pathways generate huge diversity in floral pigmentation across plan species. This is the case of tulips that generally produce yellow or red pigments but can form variegated petals if an anthocyanin regulator gene is mutated.

Nevertheless, how a colour is seen also relies on the interplay between flowers and animals. In fact, flowers selectively reflect some wavelengths while absorbing others, whereas animals differentially perceive wavelengths depending on their photoreceptors. For example, a red flower reflects red but absorbs blue, yellow, and green; this flower would appear red to humans but black to insects lacking this kind of photoreceptors!

On the other hand, the wide range of floral fragrances arise from complex mixture of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs in short) produced in floral organs – which can attract helpful pollinators or repel harmful animals. Unique floral bouquets result from the combination of several metabolites belonging to four major categories: terpenoids (e.g., limonene, myrcene), phenylpropanoids (e.g., benzoic acid), fatty acids (e.g., jasmonates, Botanical pill #2) and amino acids (e.g., derivatives of Phenylalanin).

Like flower colour, floral scent is controlled by regulatory factors and specialised biochemical pathways leading to the production of VOC – which emission varies depending on the developmental stage of the plant, the day/night cycle (circadian rhythm) and environmental conditions.

Nevertheless, not all flowers have brilliant colour or exciting fragrances for humans … just think about Amorphophallus titanum which “corpse flower”, considered the ugliest in the word (Figure 4), resembles rotten meat to attract specific carrion-eating insects that mediate pollination!