Just as intense sunlight can damage human eyesight, excessive light exposure can damage critical components of photosynthesis. A recent study aims to better understand how plants protect their photosynthetic function from excess light.

Photosynthesis is a vital process that enables plants to convert light energy into chemical energy. It consists of two stages: the light-dependent reactions and the Calvin cycle. In light-dependent reactions, light energy is captured by chlorophyll and transferred to the protein complexes photosystem II and photosystem I, which trigger electron transport to produce ATP and NADPH. These products are then used in the Calvin cycle to convert carbon dioxide into sugar.

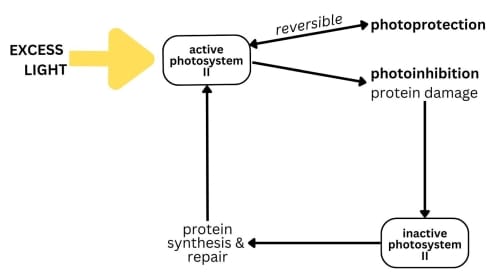

Excess light results in too much absorbed energy, leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species that can damage the photosynthetic machinery, especially photosystem II. This light-induced impairment of photosynthesis is known as photoinhibition.

The mechanisms that plants use to protect themselves from the harmful effects of excessive light are called photoprotective dependent dissipation. Photoprotection mechanisms include, amongst others, the dissipation of excess energy as heat, preventing the formation of harmful reactive oxygen species, and the transfer of energy to chlorophyll molecules in other photosystem complexes to balance energy distribution and minimize stress.

Light energy absorbed by chlorophyll can have one of three fates: it can be used to drive photosynthesis, be dissipated as heat, or be re-emitted as fluorescence. These three processes occur in competition. Fluorescence is relatively easy to measure so researchers use it to quantify photoinhibition. Generally, under high light conditions photoprotective and photoinhibition-dependent dissipation of energy increase, thereby decreasing photosynthesis and fluorescence.

Despite considerable advances in our understanding of photoinhibition, the exact mechanisms of how high-light stress inflicts damage on the photosynthetic machinery is still under debate.

Tim Nies, a PhD student at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, and his colleagues recently published a study detailing their quantification and explanation of the mechanisms behind photoinhibition. They expanded on a mathematical model of photosynthesis, then used experimental data to improve their model and pinpoint key mechanisms involved in non-photochemical quenching.

“Our model provides a dynamic description of the photosynthetic electron transport chain, non-photochemical quenching, and photoinhibition, allowing us to simulate short and long-term changes in fluorescence emitted by photosynthetic tissue. With this model, we established a framework that can be used to study the connection between photoprotective mechanisms and the damage inflicted by high light, which is far from being fully understood,” explained Nies.

The authors collected experimental data on photodamage and fluorescence which was then used to refine their model. They employed four treatments expected to produce different levels of photoprotection and photoinhibition: wildtype Arabidopsis thaliana and npq1 mutant plants were treated with either lincomycin or water as a control. npq1 mutant plants lack a crucial enzyme involved in photoprotection, while lincomycin inhibits protein synthesis in chloroplasts, preventing the repair of photosynthetic machinery due to light damage.

When exposed to excess light, npq1 plants treated with lincomycin were most sensitive to light stress, followed by wild-type plants treated with lincomycin, npq1 plants treated with water, and then wild-type plants treated with water. This range of responses provided the authors with a rich dataset to refine their model.

The authors began their computational analysis with simple assumptions for their model and gradually added complexity based on prior research until it accurately matched the experimental data. This enabled them to identify two key mechanisms of how photodamage affects fluorescence.

Plants can protect themselves from excess light by dissipating the excess energy as heat. The authors initially simulated the heat dissipation abilities of healthy photosystem II complexes and those with photodamaged complexes as being the same. Previous research suggests that photodamaged and healthy complexes of photosystem II may differ in their efficiency to dissipate heat under high light conditions. By including this factor in their model, researchers were able to more accurately simulate the variations observed in the experimental treatments.

Chlorophyll molecules can transfer energy to nearby molecules in other photosystem complexes for light energy harvesting and photoprotection. However, researchers do not agree if energy can be transferred from healthy photosystem II complexes to damaged photosystem II complexes. The authors conducted simulations that either permitted or restricted energy transfer between healthy photosystem II complexes and those with damage. They found that allowing energy transfer to damaged complexes improved the model’s ability to replicate the differences between the wild type and the npq1 mutant. These results suggest that energy transfer from healthy to damaged photosystem II might occur.

Nies concludes, “By continuing to add complexity to our model we were able to identify components critical to the model. This work helps to clarify which processes contribute to the dynamic changes of photosynthesis under high-light stress and draw special attention to the need to include them in mathematical models of photosynthesis.”

READ THE ARTICLE:

Tim Nies, Shizue Matsubara, Oliver Ebenhöh, A mathematical model of photoinhibition: exploring the impact of quenching processes, in silico Plants, Volume 6, Issue 1, 2024, diae001, https://doi.org/10.1093/insilicoplants/diae001

The code for this research is openly available in GitHub at https://gitlab.com/qtb-hhu/models/2023-photoinhibition.