Modern roses, famous for their colors and ability to bloom again and again, owe much of their genetics to Chinese old garden roses. Until recently, it was unclear which wild species contributed to modern roses and where did the key gene for repeat flowering come from. Now, a new study published in Annals of Botany identified the wild ancestors of Chinese old garden roses and traced the origins of the key gene responsible for continuous flowering.

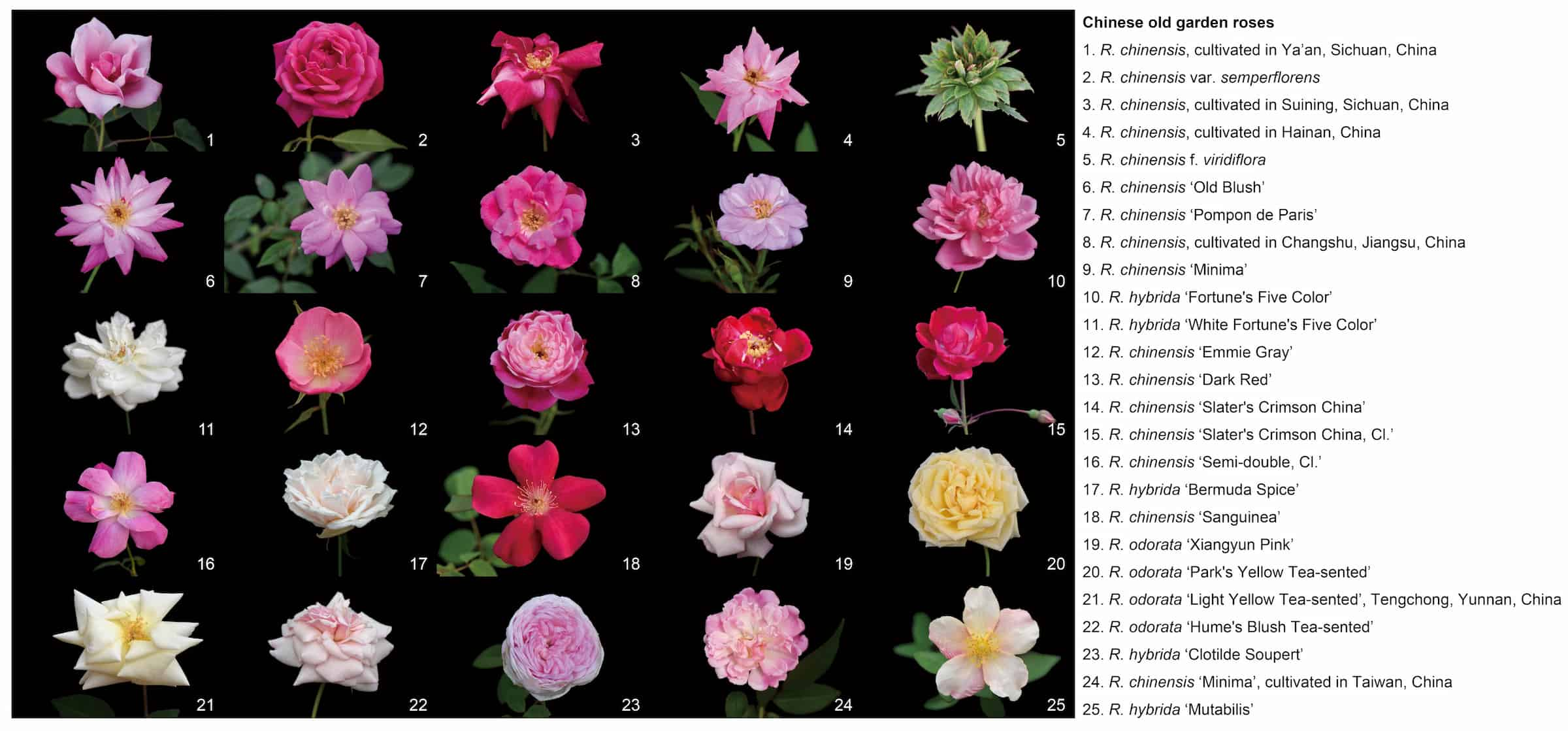

By examining 25 of the most classic diploid Chinese old garden roses, and their wild relatives from across East Asia, Cheng Zhang and collaborators reconstructed the complex family tree of these plants. Their analysis not only identified the wild donors that contributed to the roses’ genetic composition but also traced the geographical origins of a gene that transformed how roses grow and flower.

At the heart of the mystery lies RoKSN, a gene strongly linked with a plant’s ability to flower continuously rather than in a single burst each year. To track the gene’s journey, the research team compared genetic markers across a wide range of roses. They examined nuclear DNA regions, chloroplast genes inherited through maternal lines, and a series of highly variable DNA repeats known as EST-SSRs. They also sequenced RoKSN itself across species within Rosa sect. Chinenses.

The results were surprising. The majority of Chinese old garden roses could be traced back to early hybridisation events involving three wild donors: Rosa chinensis var. spontanea, Rosa odorata var. gigantea, and Rosa multiflora var. cathayensis. From these, a series of distinct cultivar groups emerged.

One group, known as “Old Blush,” arose from hybrids of R. chinensis var. spontanea and R. multiflora var. cathayensis. This group then gave rise to others: the “Slater’s Crimson” roses, produced when Old Blush was crossed with R. kwangtungensis; and the “Tea Roses,” formed from hybrids of Old Blush and R. odorata var. gigantea. A smaller number of cultivars carried even more complex genetic compositions, with input from multiple donors.

This pattern shows that Chinese old garden roses are not the result of a single domestication event. Instead, they represent a web of hybridisations, in which cultivated forms repeatedly interbred with both each other and with different wild species.

All the Chinese old garden roses analysed carried an identical form of the RoKSN-copia allele, a version of the gene containing a retrotransposon, a mobile piece of DNA that disrupted its normal function. This mutation appears to have arisen only once, and then spread through successive hybridisations.

Geographically, the researchers traced the haplotypes associated with this allele to the Sichuan Basin, a region in southwestern China. By contrast, roses cultivated in the nearby city of Ya’an showed no evidence of hybrid ancestry and were genetically close to the wild R. chinensis var. spontanea. Intriguingly, these may represent some of the earliest cultivated roses to carry the RoKSN-copia allele – perhaps the original link between wild species and the continuous-flowering garden cultivars that followed.

The finding that continuous flowering in roses likely originated from a single mutation in a specific region of China illustrates the role of chance in evolution and domestication. Without that mutation and the subsequent propagation and hybridization by gardeners, modern roses would likely be very different.

READ THE ARTICLE

Zhang C., Jiang Z., Yang S. Li S., Liang Z, Gao X (2025) “Molecular investigation of the progenitors, origin, and domestication patterns of diploid Chinese old garden roses” Annals of Botany. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcaf208

Cover image: Rosa ‘Old Blush’ by Salicyna / Wikimedia Commons. CC-BY-SA