Plants and pollinators have developed an intimate relationship over time. Both have evolved physiological and morphological strategies to get the most out of their interactions. Pollinators, for example, have evolved specialised body parts, such as hairy bodies in bees, elongated proboscises in butterflies, and elongated bills in hummingbirds –all aimed at collecting and transporting pollen and nectar more efficiently. In turn, plants have developed methods to attract pollinators, including vibrant colours, enticing scents, and large floral displays. However, these strategies can inadvertently also attract herbivores, pressuring plants to develop defence mechanisms.

Among the various defence mechanisms employed by plants, one could mention the use of the different colour vision capacities of mutualists and antagonists, mechanical and chemical defences, and camouflage. Some plants, for example, take advantage of the fact that different animals see colours differently. Red-coloured flowers can attract birds while being less noticeable to certain insects, such as bees and ants, that can act as antagonists in search of nectar. In this case, the red colour helps the flowers avoid these insects, serving as a defence mechanism. Mechanical defences include structures like thorns and spines, while chemical ones involve the production of toxic or deterrent compounds. Finally, camouflage has emerged as a defensive strategy in plants in response to selection pressure from herbivores, and it is the main defensive strategy of the alpine plant Fritillaria delavayi.

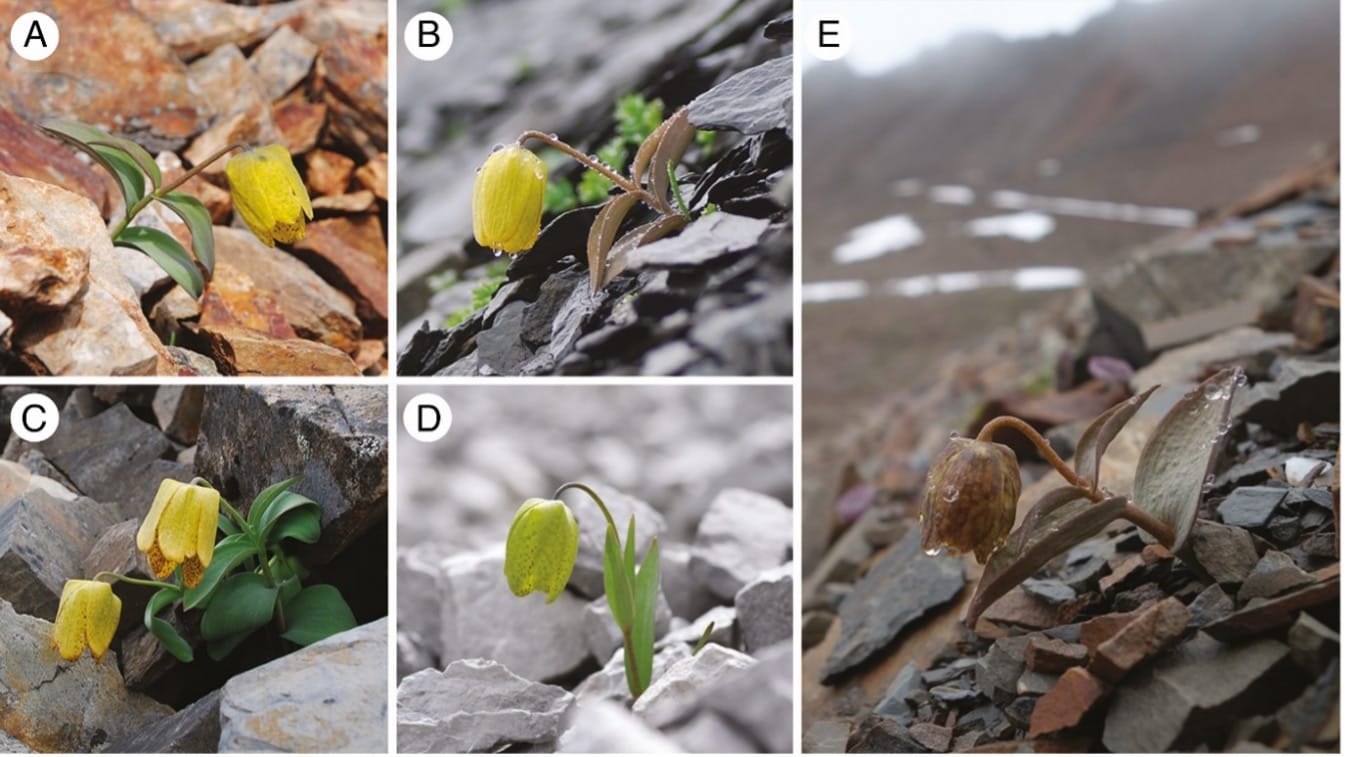

Fritillaria delavayi shows a range of leaf and flower colours among different populations, from green to cryptic shades like grey or brown, which help the plant blend into its rocky surroundings. This adaptation varies among populations and is influenced by pressures from human harvesting for medicinal purposes. In most areas, the plant produces yellowish flowers that bees pollinate. However, in some populations, flowers are camouflaged to match the colour of rocks.

If the pollination of these cryptic flowers and whether their colouration impacts the number of seeds produced have long remained unanswered questions until a recent study led by Tao Huang and his team. Their research involved pollination experiments, including measuring floral characteristics, estimating floral colours as perceived by different pollinators, analysing floral scents, and investigating reproductive success across five populations in the northwest Yunnan province, southwest China.

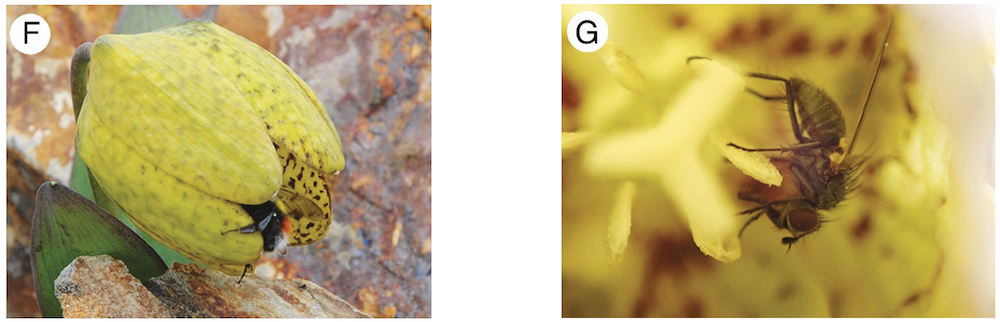

Surprisingly, they found that despite their camouflaged flowers, F. delavayi plants produced a high number of seeds, meaning that even when cryptic, pollination still occurs. How? By shifting their primary pollinators from bumblebees to flies. In the population with camouflaged flowers, flies are the exclusive pollinators, unlike in yellow-flowered populations, where bumblebees dominate. The camouflaged flowers are smaller and perfectly suited for these tiny fly pollinators.

Interestingly, the camouflaged flowers blend seamlessly into their rocky surroundings, making them nearly invisible to bumblebees and flies alike. Bumblebees are well-known pollinators in alpine zones and possess trichromatic colour vision, which means they have three types of colour receptors in their eyes. This ability allows them to differentiate various colours, such as the yellow hues of F. delavayi flowers. In the alpine environment, where plant diversity is often low and pollination efficiency is critical for reproductive success, bumblebees’ keen colour vision makes them particularly effective at locating and pollinating the yellow flowers of F. delavayi.

Similarly, flies also play crucial roles in cold environments and possess trichromatic colour vision. Anthomyiid insects, the main pollinators in the camouflaged population, are known to be important pollinators of other alpine and arctic flora. Previous studies have shown that flies can discern small colour differences but rely more on scent than sight, enabling them to locate these hidden flowers. So, in this case, they believe that flies are guided mainly by the scents.

In terms of reproductive success, populations with camouflaged and non-camouflaged flowers showed comparable rates of fruit and seed production. Despite being less efficient pollinators than bumblebees, flies visit camouflaged flowers significantly more often than bumblebees in other populations. This frequent visitation compensates for their lower efficiency, resulting in similar rates of fruit and seed production.

The findings of Huang and colleagues’ research suggest that F. delavayi has evolved different strategies to attract pollinators depending on its flower colour and environment. The camouflaged flowers seem to have adapted to less visually conspicuous methods of attracting pollinators, relying more on scent and being smaller to match their primary pollinators, flies. This adaptation might be a response to the high levels of harvesting pressure, leading to the survival of those plants that are less visible and thus less likely to be picked by herbivores. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for conservation efforts, particularly in areas where the plant faces significant harvesting pressure. Protecting both the plant and its pollinators is essential for maintaining the ecological balance and ensuring the survival of this species.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Huang, T., Song, B., Chen, Z., Sun, H., & Niu, Y. (2024). Pollinator shift ensures reproductive success in a camouflaged alpine plant. Annals of Botany, mcae075. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcae075

Victor H. D. Silva is a biologist passionate about the processes that shape interactions between plants and pollinators. He is currently focused on understanding how plant-pollinator interactions are influenced by urbanization and how to make urban green areas more pollinator-friendly. For more information, follow him on X as @another_VDuarte

Portuguese version by Victor H. D. Silva (in progress).

Featured Image: Non-camouflaged Fritillaria delavayi flowers being visited by a bumblebee from Huang et al. (2014).