Changing colours of leaves mark seasonal progression in temperate regions: while bright green baby leaves announce springtime, the gorgeous yellow to red palette of falling leaves anticipate wintertime. In this Botanical Pill, we will explore the microscopic life of a leaf, from its birth at the shoot apex to its death through a life cycle-dependent process called senescence.

What is a Leaf?

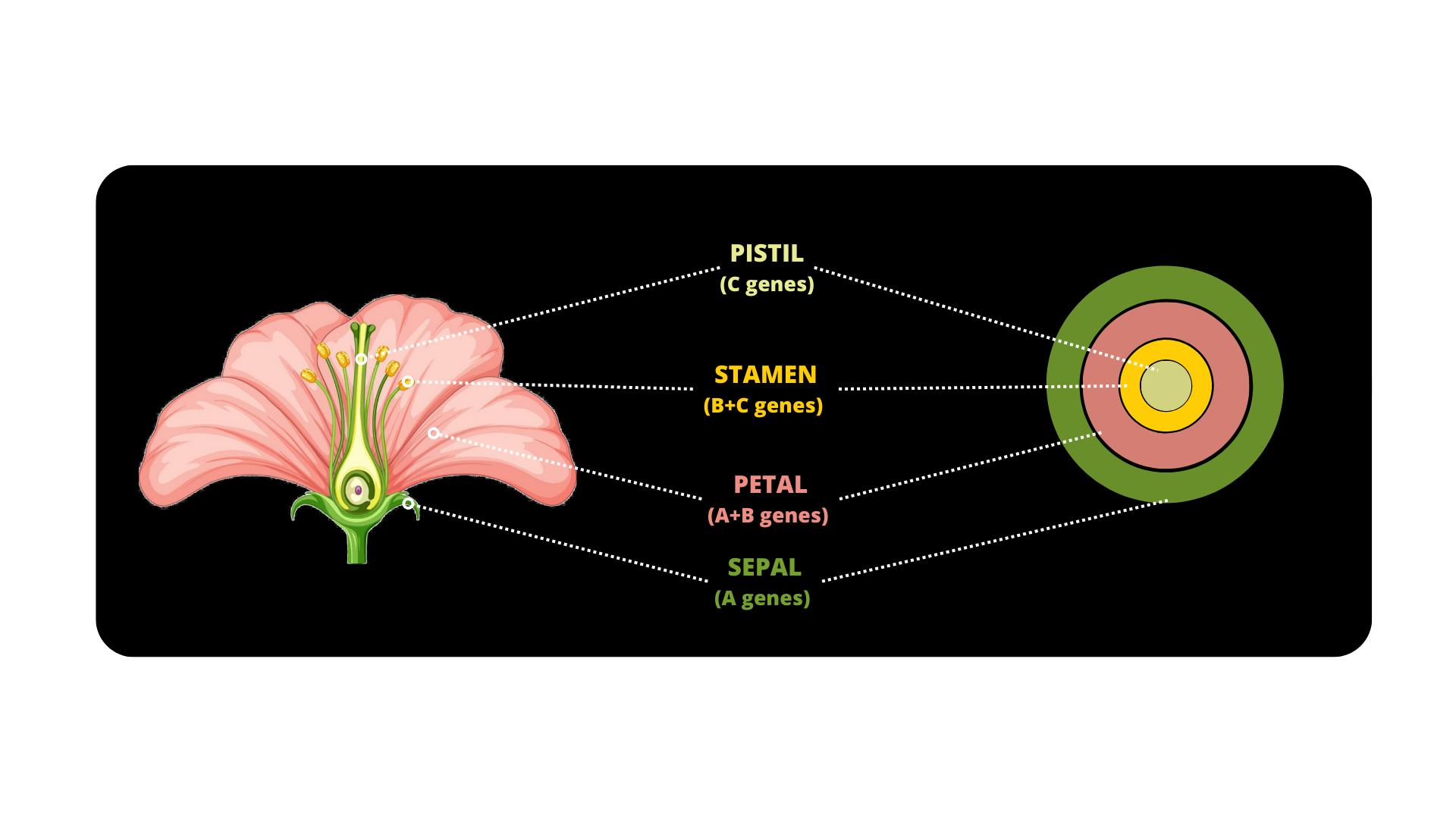

At the end of the XVIII century, the German writer and brilliant philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe proposed the leaf as the archetypal form for all aerial parts of the plant growing from the apical meristem (i.e., pool of stem cells enclosed in the shoot apex). According to the hypothesis formulated in his famous work Metamorphosis of Plants, “The organs of the vegetating and flowering plant, though seemingly dissimilar, all originate from a single organ, namely, the leaf”.

During the evolutionary history of plants (Botanical pill The evolution of land plants), true leaves first developed in vascular plants more than 400 Million Years Ago (Figure 1), and became the major site for photosynthesis and transpiration. In short, leaves harvest energy from the sun and capture carbon dioxide (CO2) from atmosphere to produce nutrients. Precisely, photosynthesis takes places in chloroplasts – specialized organelles of the plant cell that contain pigments able to absorb sunlight and transform CO2 into organic compounds (e.g., sugars) essential for plant growth. As by-products, plants release water vapour and oxygen, a fundamental element of the air we all breath.

The Birth of a Baby Leaf

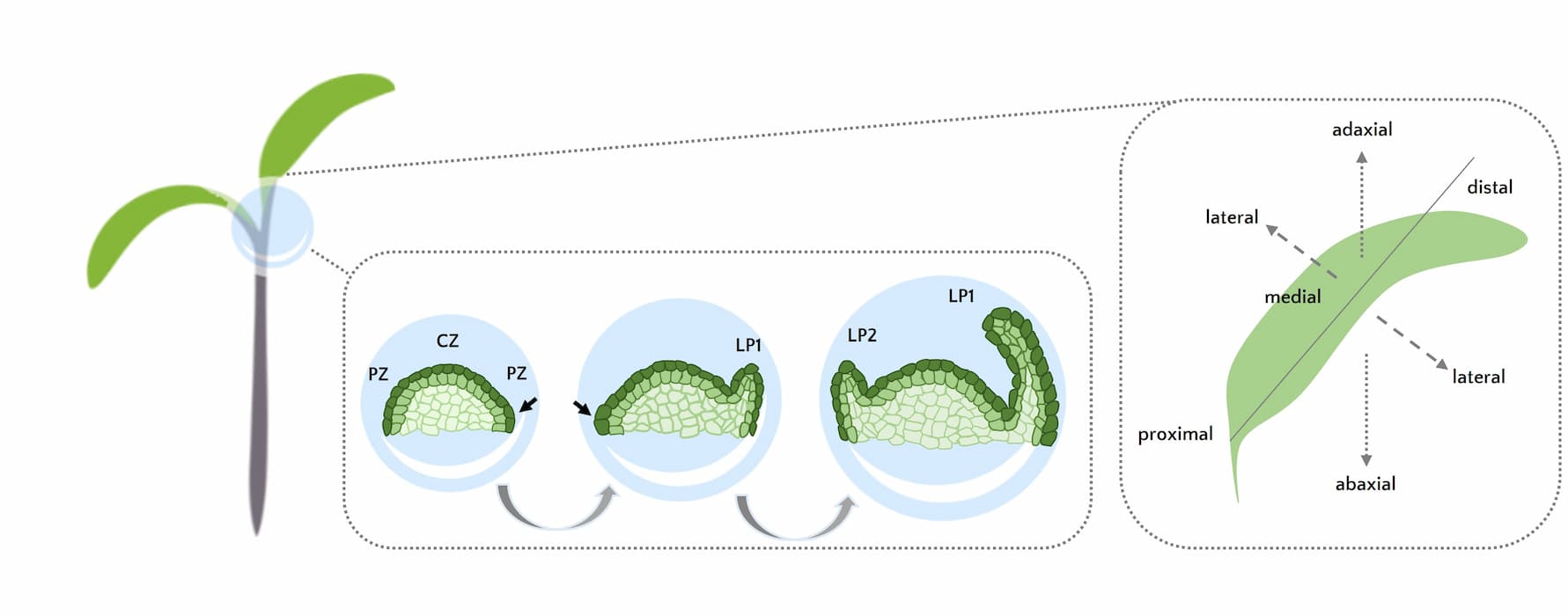

Upon seed germination, pluripotent cells of the Shoot Apical Meristem (SAM) give rise to all above-ground organs throughout a plant life cycle. While cells of the central zone maintain the pool of undifferentiated cells by slowly dividing, cells of the peripheral zone acquire a determinate identity to generate lateral appendages following three main axes (Figure 2):

- the longitudinal axis, that demarcates basal and apical regions respect to the SAM;

- the dorso-ventral axis, that defines the adaxial-abaxial polarity (upper and lower surfaces);

- the medio-lateral axis, that drives the expansion of the leaf from the middle domain.

To know more about the complex Gene Regulatory Network underlying leaf development, have a look at the comprehensive review, published in The Plant Cell by Prof. Neelima R. Sinha (University of California Davis, USA) and colleagues, that encompasses decades of molecular genetics studies in the field.

What Makes a Mature Leaf?

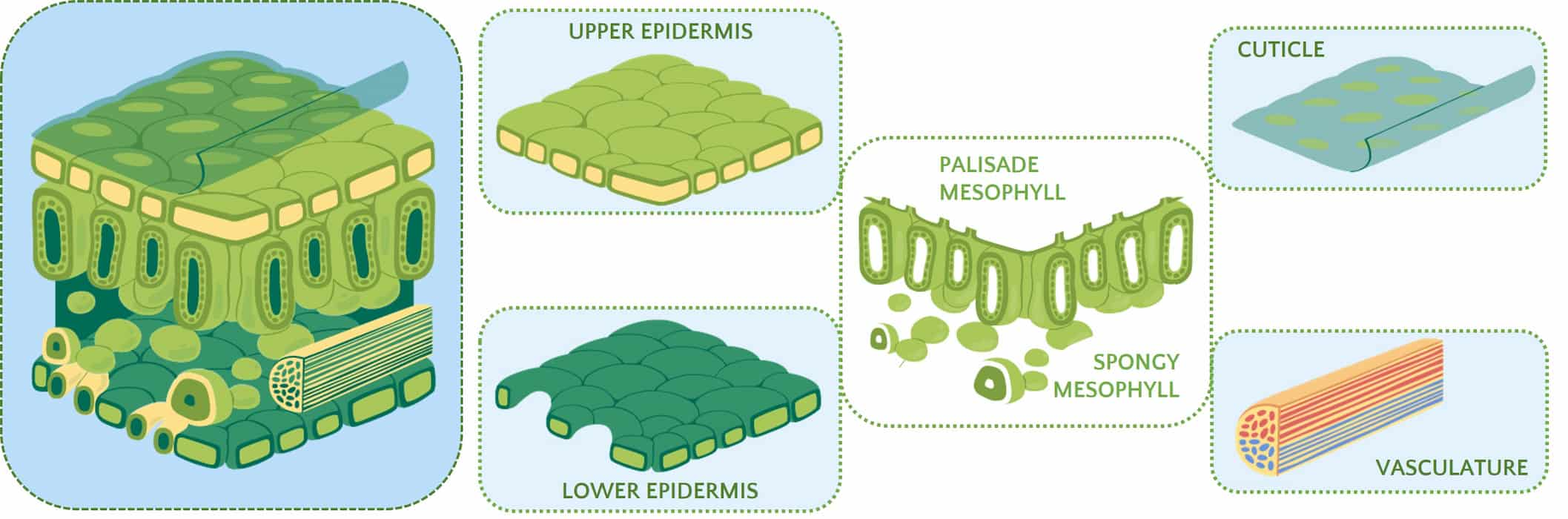

At maturity, a typical leaf is composed of a stalk that connects the flat part (called blade) to the stem. Despite the great diversity in leaf morphology, leaves share a common structure (Figure 3), composed of three tissues with different functions:

- the EPIDERMIS maintains the structural integrity of the organ;

- the MESOPHYLL performs photosynthesis for plant functioning;

- the VASCULATURES transports water, nutrients and photosynthates.

Functional leaves contain high amount of chlorophylls – photosynthetic pigments that absorb all wavelengths in the visible light spectrum but green, which is reflected in the environment. The human eye perceives young and mature leaves as green organs because chlorophylls are more abundant and mask other pigments.

The Leaf Under the Microscope: skin, pores & hairs

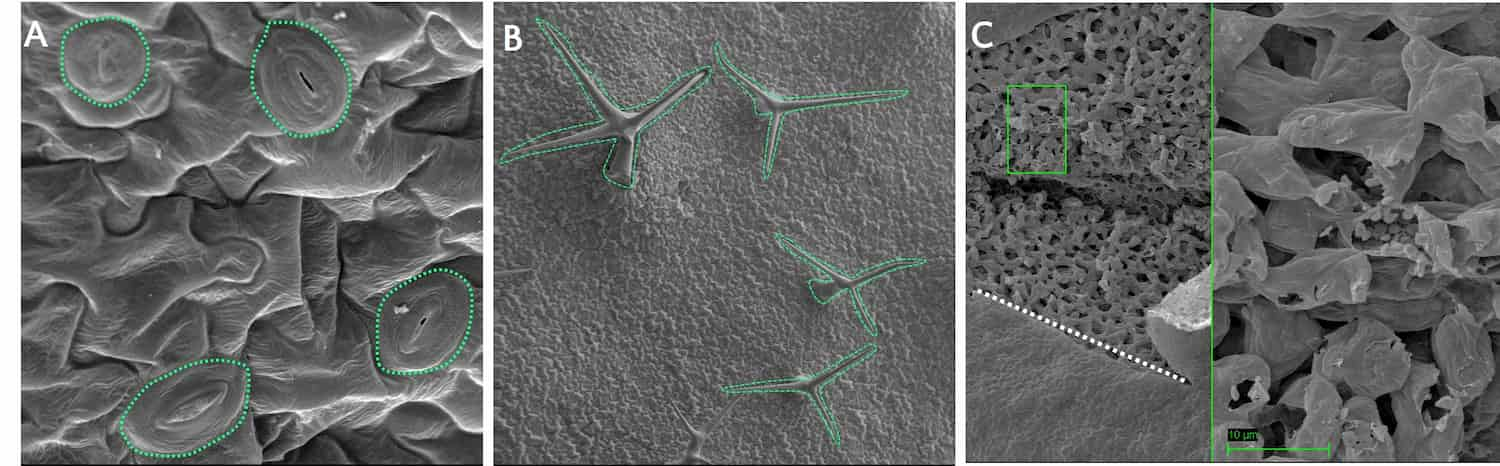

A closer look at mature leaves reveals the presence of specific cell types (e.g., pavement cells, stomata and trichomes, Figure 4) that play key roles in plant interaction with the environment as well as in plant defence against abiotic and biotic stresses (Botanical Pill Plants under pressure).

Puzzled-shaped pavement cells with interlocking lobes are found on both epidermal surfaces. Thanks to their peculiar geometry, outermost cell layers protect the internal structures of the leaf from external agents and guide developmental processes by providing mechanical strength. They also produce the cuticle – a protective film composed of lipid polymers and waxes that acts as a barrier for water and microorganisms.

Stomata (from the Greek stoma meaning “mouth”) are pores that regulate gas exchange with the atmosphere. Two guard cells surrounding the pore open and close depending on environmental conditions (e.g., changes in time of the day, humidity, temperature), thus controlling CO2 input for photosynthesis and water loss through transpiration.

Trichomes (from the Greek trichōma meaning “hair”) are protuberances that protect plants against herbivores. They act as physical obstacles to impede animal feeding and/or chemical defence to induces toxic or even lethal reactions upon contact. Trichomes are also crucial for plant response to abiotic stresses by: 1) preserving plant surface from frost in very cold areas, 2) breaking up the flow of air in windy areas, thus reducing water loss via transpiration, 3) protecting delicate tissues by reflecting sunlight in sunny areas, and 4) increasing moisture retention in foggy areas.

The Death of an Old Leaf: plant aging and colour change

After differentiation and maturation, leaves undergo an age-dependent developmental stage called leaf senescence. This active degenerative process encompasses changes at different levels (e.g., molecular, biochemical, cellular, physiological) and is genetically programmed but environmentally influenced

Senescence starts with the disassembly of plant organelles (e.g., chloroplasts and mitochondria), and continues with the degradation of macromolecules including proteins, lipids, and photosynthetic pigments. Senescent leaves change colour and become yellow because chlorophylls undergo fast degradation, thus making more visible other accessory pigments called carotenoids that reflect orange.

In annual and biannual flowering plants, leaves senesce when the plant completes its life cycle and redistributes nutrients from dying organs to the developing seeds. In perennials, leaves senesce in autumn when the plant faces adverse weather conditions and exports nutrients to storage organs (stems and roots) until next spring. Thus, leaf senescence represents an effective recycling strategy to remobilize important elements (e.g., Nitrogen) to the offspring or to new organs that will form in the following spring.

To Fall or Not to Fall: Deciduous Versus Evergreen Trees

Throughout their lives, several perennial species develop new green leaves or detach old yellow leaves depending on the season. This is the case of deciduous trees (e.g., maple, oak, birch) that lose their broad leaves in autumn as an adaptative strategy to survive in winter. In this way, trees can preserve nutrients and reduce water loss via transpiration. But how do they decide? Intriguingly, deciduous forests in temperate regions perceive changes in ambient temperature, while those in tropical and subtropical regions sense alteration in rainfall patterns.

On the contrary, evergreen trees (e.g., pines, cypresses, spruce) maintain their leaves regardless of seasonal progression. They do replace old leaves with new ones, but this process occurs at very slow pace.

Beware, there is still life below a senescent leaf: a carpet of fallen leaves can be the perfect hiding place for small animals and winter shelter for all those organisms living in the soil!

Suggested Reading

What Is a Leaf? · Frontiers for Young Minds (frontiersin.org)

von Goethe JW (1790) Herzoglich Sachsen-Weimarischen Geheimraths Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären. Ettinger

Glossary of leaf morphology – Wikipedia

Leaf Senescence: Systems and Dynamics Aspects | Annual Review of Plant Biology (annualreviews.org)