Rice is a staple food in major parts of the world and not only provides calories and nutrients to billions of people every day but is also an integral part of their culture, especially in Asian countries. Traditionally celebrated as a symbol of life and fertility, the grain’s shiny image has suffered in recent years since it has been identified as the main food source of inorganic arsenic, a toxic trace element found in rocks and sediments around the globe.

Arsenic is released into the environment as a by-product of mining activities and the use of arsenic-containing pesticides. Chronic exposure increases the risk of various forms of cancer, as well as pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases. Nowhere can the adverse effects of arsenic be better seen than in Bangladesh, where what started out as a national health program to save lives ended in the worst mass poisoning in history.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, cholera and other infectious diseases were a constant threat to the population that relied on polluted rivers and lakes as a main water sources. The 1970s saw massive efforts from the government and international aid agencies to supply the nation with “cleaner” groundwater by building thousands of wells across the country. Unbeknownst to all, the groundwater in Bangladesh is naturally high in arsenic, a slow killer that only reveals its grim face after years of constant exposure. Millions of people were, and still continue to be, slowly poisoned by drinking arsenic water and eating arsenic rice. Bangladesh has the highest rice consumption worldwide with over 250 kg per year per capita, the daily diet thus represents a significant route of arsenic exposure. The problem may be especially severe in Bangladesh, but high arsenic levels in soils and consequently rice are also found in China, India, Southeast Asian countries, and parts of the United States, among others.

No other crop accumulates as much of this element as rice. The low oxygen conditions in the flooded paddy soils that rice is grown in make arsenic more available for uptake into the plant. Since the chemical properties of arsenic are similar to phosphate and silicon, for which rice has highly efficient uptake and transport systems, it accumulates to high concentrations in the grain. The problem is aggravated when contaminated water is used for rice field irrigation. Changing the farming practice to ones that allow more oxygen in the soil is unfeasible in many low-lying waterlogged areas, and also drastically increases the bioavailability and plant uptake of cadmium, another highly toxic element of major concern for food safety.

In a recent paper published in the Journal of Experimental Botany, Gui and colleagues have approached this problem and genetically engineered rice with low concentrations of arsenic and cadmium in the grain. Within plant cells, both elements are stored in the vacuole, a membrane-bound organelle where toxic compounds are sequestered. Before being transported into the vacuole the metals are bound in the cytosol to small detoxifying molecules called phytochelatins to prevent their interference with metabolic processes. Gui and colleagues have generated rice overexpressing a phytochelatin-synthesizing enzyme and two transporters that facilitate arsenic and cadmium uptake into the vacuole.

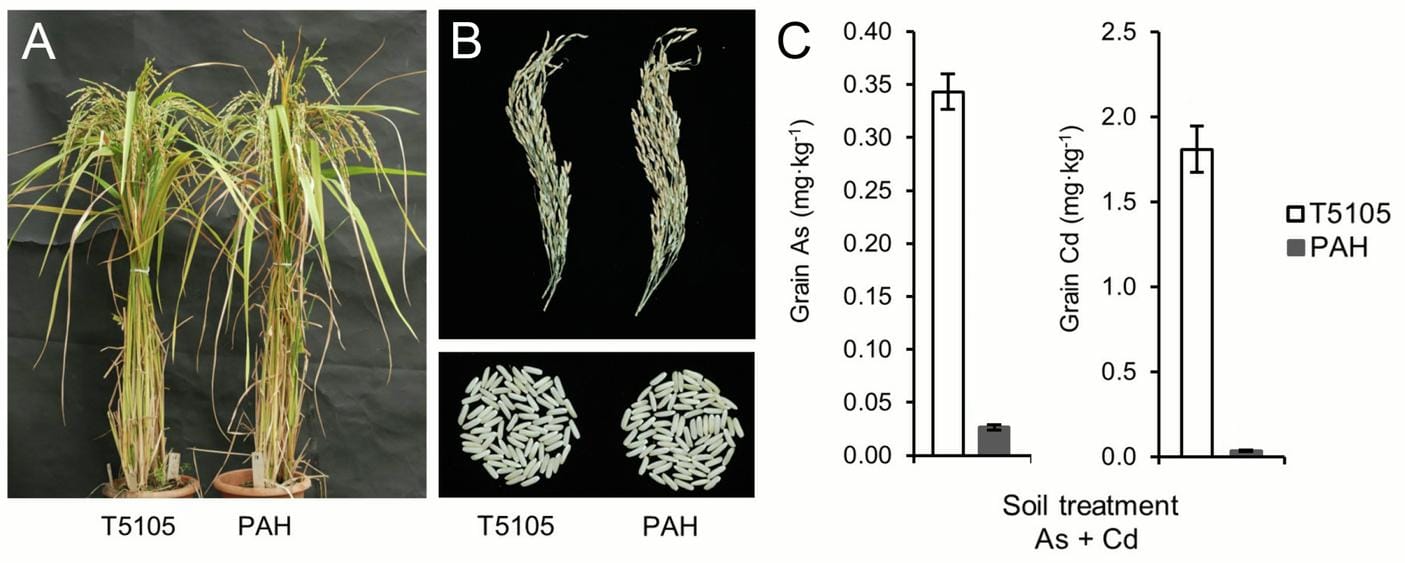

These engineered plants accumulated increased levels of arsenic and cadmium in roots and nodes, the thickened joints along the stem at which leaves emerge, and significantly reduced allocation into the grain. In fact, even when grown in cadmium- and arsenic-contaminated soil, the concentrations of the toxic elements in the grain were far below the current limits set by the World Health Organisation considered safe for consumption. Importantly, the overexpression of these genes did not impact plant growth, reproduction, and agronomic traits such as panicle morphology and seed size and weight were not negatively impacted by the gene overexpression. The authors show convincingly that this could only be achieved by gene-stacking through the effect of overexpressing several selected genes in the plant at the same time.

This research is an impressive example of how biotechnology can be used to secure food safety. With the support from Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory and Temasek Trust, the research team is now aiming at commercialising the low-arsenic and low-cadmium rice to benefit both rice farmers and consumers, and the approach holds much potential to improve human health and save lives.

READ THE ARTICLE

Gui, Y., Teo, J., Tian, D., & Yin, Z. (2024). Genetic engineering low-arsenic and low-cadmium rice grain. Journal of Experimental Botany, 75(7), 2143-2155. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erad495.

Mareike Jezek

Dr. Jezek is an Assistant Editor at the Journal of Experimental Botany, one of the official journals of the Society for Experimental Biology.