Over 30 years ago, Diekmann and colleagues first observed that changes in vacuole morphology within guard cells accompany stomatal opening and closing. Recent experiments, however, suggest that the traditional understanding of vacuole fusion mechanisms—particularly the role of specific metabolites—might be more complex than previously thought.

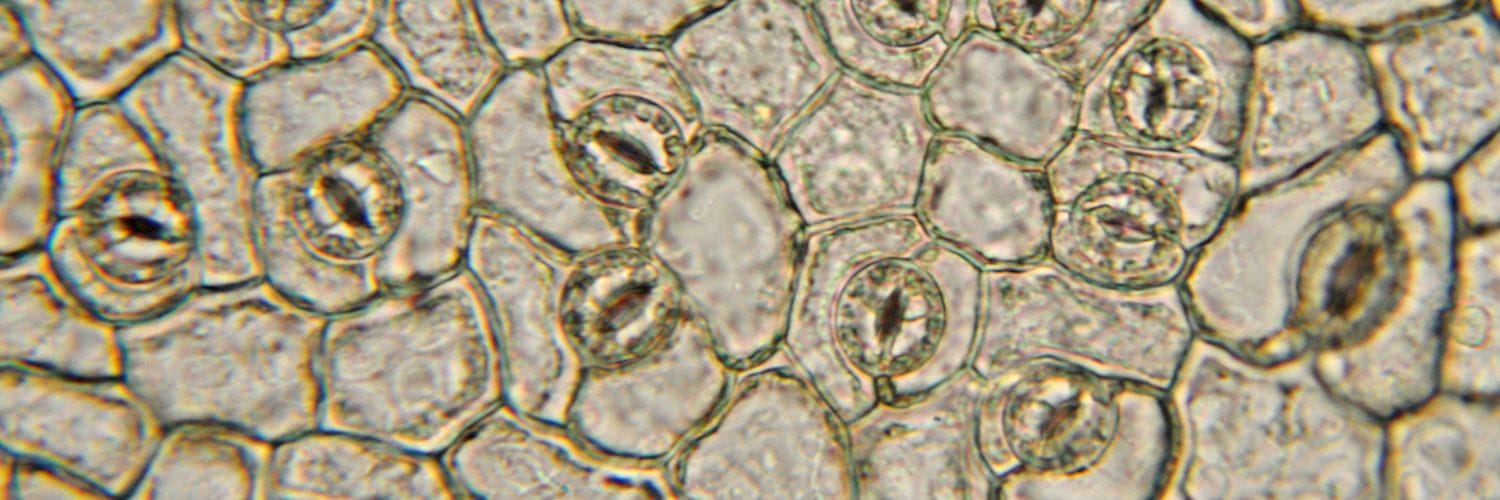

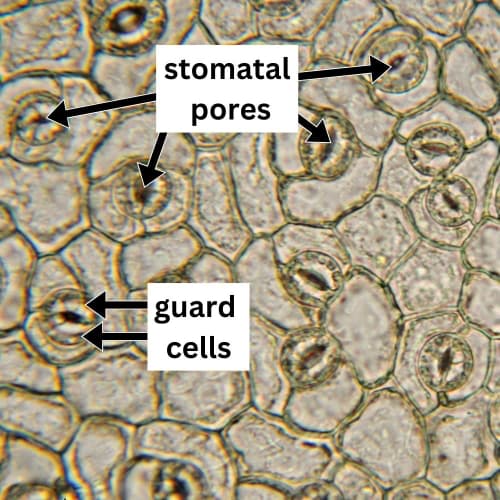

Stomata are small openings on the surfaces of leaves, stems, and other plant organs. They play an important role in allowing movement of water, carbon dioxide and oxygen into and out of the plant.

Each stoma is flanked by two specialized cells known as guard cells, which control their opening and closing. The swelling of guard cells leads to the opening of the stomata, while the return of guard cells to their original shape results in closure. The volume of guard cells can increase by as much as much as 40% during opening!

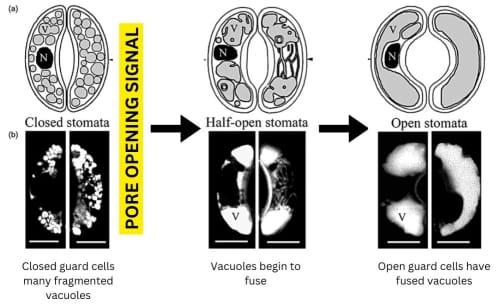

Stomatal opening occurs in response to environmental cues such as light, humidity, and carbon dioxide concentration. For instance, stomata tend to open during the day when light is available for photosynthesis and close at night or during drought conditions. When stomata are closed, the vacuoles in guard cells are numerous and fragmented, whereas, when stomata are open, the guard cells contain a single large vacuole. Notably, vacuole membrane fusion is necessary for full opening of the stomata.

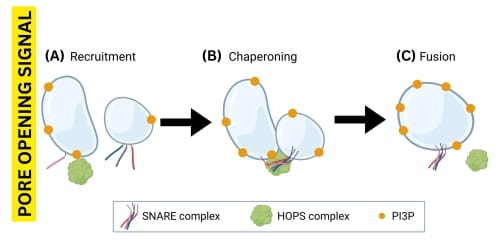

The prevailing theoretical framework for the series of molecular processes leading to plant vacuole fusion is that after the pore opening signal occurs:

- PI3P recruits HOPS to the vacuole membrane;

- HOPS tethers a pair of vacuoles and chaperones the SNARE proteins located on the vacuole membrane to bind and form a HOPS:trans-SNARE super-complex; and

- the new supercomplex fuses the vacuole membranes, and HOPS is released to catalyze further fusions (Fig. 1).

“Protein complexes” are assemblies of two or more proteins that interact with each other to perform a specific biological function. The prefix “trans” refers to protein complexes that are located on different membranes, whereas “cis” indicates that the proteins are on the same membrane. Therefore, when SNARE proteins are brought together by HOPS and interact, they form a trans-SNARE complex; after membrane fusion occurs, they become a cis-SNARE complex.

The results of one experiment challenge the current framework.

Vacuoles of leaves exposed to the metabolite wortmannin (i.e., wortmannin treatment) which removes PI3P, continue to fuse. Since PI3P is believed to be essential for recruiting HOPS, one might expect that removing PI3P from this system would hinder the cell’s ability to fuse vacuoles.

Were scientists mistaken in their explanation of the role of metabolites in the vacuole fusion process?

A recent article in in silico Plants aimed to explain this phenomenon. Postdoctoral Researcher Dr. Charles Hodgens, formerly at University of Tennessee-Knoxville and now at North Carolina State University, led a study that developed and tested the feasibility of an alternative theoretical framework on the mode of action of HOPS and PI3P in plant vacuole fusion.

The authors hypothesized that removing HOPS from the HOPS:trans-SNARE super-complex might be crucial for fusion, meaning HOPS could both promote and inhibit vacuole fusion. To confirm this, they needed to identify a protein that could displace HOPS. Finding no evidence in plant literature, they turned to yeast for clues. This led them to the candidate protein Sec17, known for its role in yeast membrane fusion.

Next, the authors set out to confirm the presence of Sec17 in plants. They obtained the amino acid sequence for Sec17 and searched the protein database BLASTP for the matching sequence in plants. They found a matching sequence for a protein found in guard cells, suggesting that it likely performs the same or a related function in plants.

This finding supported their hypothesis and prompted them to propose a new theoretical framework for the molecular processes leading to plant vacuole fusion.

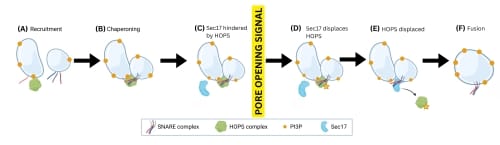

The framework is as follows:

- HOPS is recruited to the vacuole by PI3P;

- HOPS tethers a pair of vacuoles and chaperones their SNARE proteins to form a HOPS:trans-SNARE super-complex;

- HOPS prevents fusion activity by hindering the access of Sec17. After the pore opening signal occurs;

- Sec17 reduces binding affinity between HOPS and trans-SNARE;

- HOPS is displaced; and

- the trans-SNARE fuses the vacuole membranes.

The authors tested the validity of this framework using a simulation model of vacuole fusion dynamics that they developed. This model integrates established knowledge about the molecular mechanisms involved in vacuole fusion with observations of vacuole morphology. These observations were made by the authors, who conducted microscopy analyses to observe the state and speed of vacuole fusion in live cells.

The model predicted the same result as observed, confirming that the molecular processes described by their framework were accurate.

After confirming that the presence of HOPS in the HOPS:trans-SNARE super-complex inhibits vacuole fusion using the model, the authors speculated on why Wortmannin treatment does not prevent vacuole fusion. After exposure to Wortmannin, without PI3P recruiting HOPS, the HOPS:trans-SNARE super-complex that inhibit vacuole fusion are not formed. However, Sec17 continues to reduce binding affinity between HOPS and trans-SNARE of the existing HOPS:trans-SNARE super-complexes at the same rate, causing HOPS to disassociate from the super-complex and resulting in vacuole fusion.

This work demonstrates the value of models in evaluating theoretical frameworks to enhance our understanding of biological functions.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Charles Hodgens, D T Flaherty, Anne-Marie Pullen, Imran Khan, Nolan J English, Lydia Gillan, Marcela Rojas-Pierce, Belinda S Akpa, Model-based inference of a dual role for HOPS in regulating guard cell vacuole fusion, in silico Plants, 2024;, diae015, https://doi.org/10.1093/insilicoplants/diae015

Code used to perform the analyses for this paper are available at https://gitlab.com/hodgenscode/hodgens2023.