Seed banks are a very important tool in the preservation of species. For example, a species that is threatened with extinction by exposure to environmental stress can be preserved by storing dry seeds at low temperatures in specially controlled facilities. However, not all species produce seeds that are still viable after being treated or stored under the current United Nations guidelines. This is particularly true of forest species. Over 20% of these species’ seeds die during preservation and storage.

“The longevity of seeds in storage is of great importance to the conservation of both wild and crop species, determining how long a seed collection will remain useful for regenerating whole plants,” write Sommerville et al in their recent publication on seed preservation in the Annals of Botany. “This is particularly important to species on the verge of extinction, for which recovery may depend entirely on seeds held in a gene bank.”

Unfortunately, studies on seed longevity have found that some seeds live less than a decade in storage, while others are viable for centuries. There is even the rare case of a 2000-year-old date palm found stored in a Judean desert archaeological site that was successfully germinated after its discovery.

And so, when dealing with species facing extinction, it’s especially important to improve our understanding of seed storage conditions to boost the chances of germination on some unknown future date. This is because collecting more seeds is often impractical, and it will, of course, be impossible if extinction occurs.

“Re-collection often requires travel to remote locations, sometimes to areas accessible only by foot, or to which access may be limited during the rainy season (when the seeds of some rainforest species are dispersed) or following extreme events such as fires and floods,” write Sommerville et al. This makes collection often infeasible and better storage of samples collected imperative.

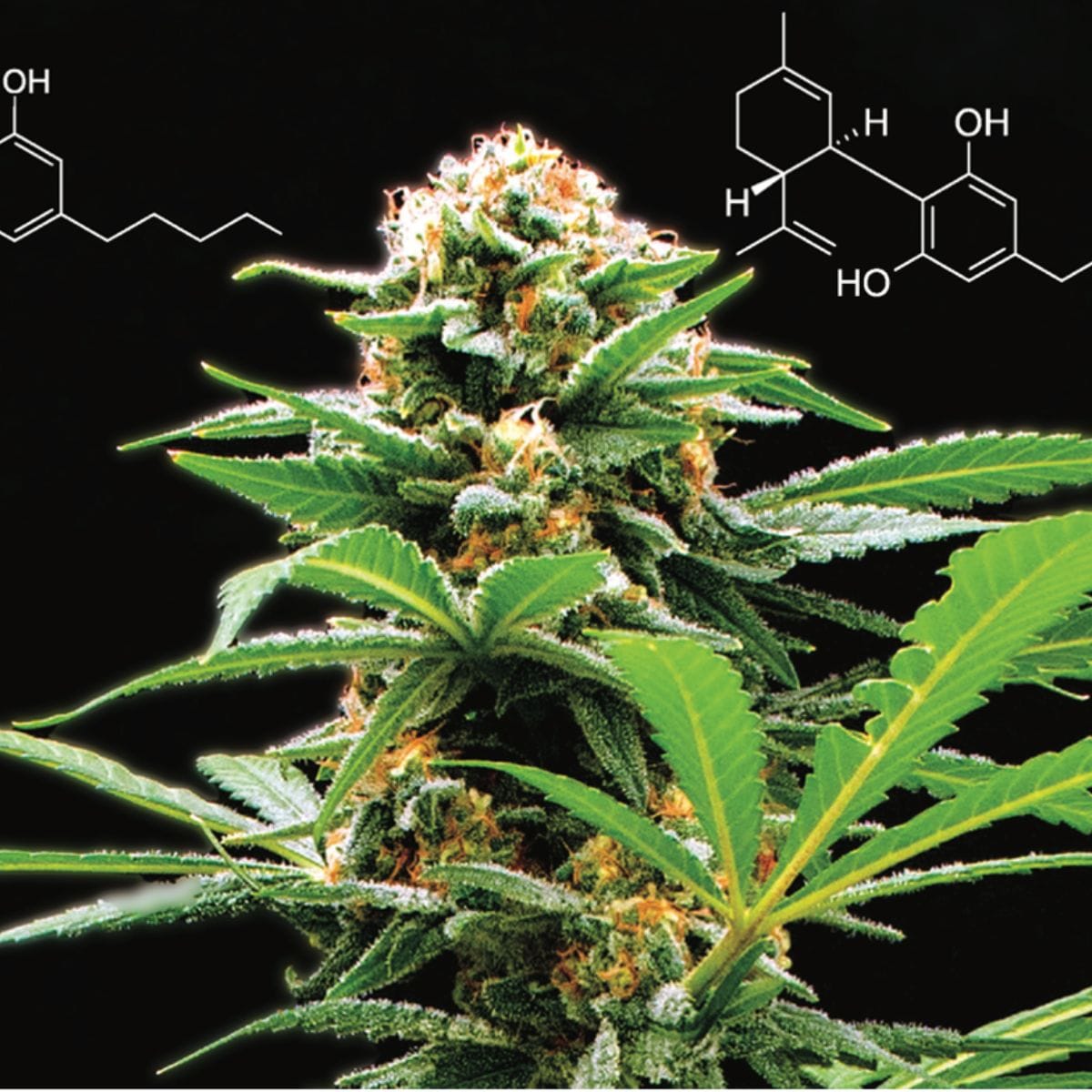

To increase the odds that seed preservation and storage is successful for rainforest species, Sommerville et al investigated the role of ‘storage lipids’ in the seeds of 23 rainforest species. Storage lipids are energy molecules that consist of triacylglycerols (link here to a definition) and depending on their chemical makeup have different melting and crystallisation properties.

“Here we investigated seeds from 23 species native to the rainforests of Eastern Australia that had been found to be short-lived under standard gene-banking conditions,” write Sommerville et al. “We quantitatively characterized the crystallization and melting behaviour of TAGs [triacylglycerols] in vivo and in extracted lipids to determine whether these were directly related,”

Sommerville et al found that the seeds from these species were relatively tolerant of drying but had reduced viability after exposure to freezing temperatures (-20°C). Furthermore, seed storage lipids played a definitive role in the loss of viability, which crystallised during warming treatments.

However, the effect of warming varied widely across species, with some being more sensitive than others. This complicates seed storage practices because cooling and warming rates must be empirically optimised for each species. In the short term, Sommerville et al recommend that species suspected to have poor longevity due to their lipid composition be stored as dry seeds at temperatures warmer than -20°C.

In this way, we can hopefully bank our seeds for a flourishing tomorrow.

READ THE ARTICLE

Sommerville, K.D., Hill, L., Offord, C.A. and Walters, C. (2025) “Thermal behaviour of lipids in short-lived seeds of Australian rainforest species,” Annals of Botany, (mcaf181). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcaf181