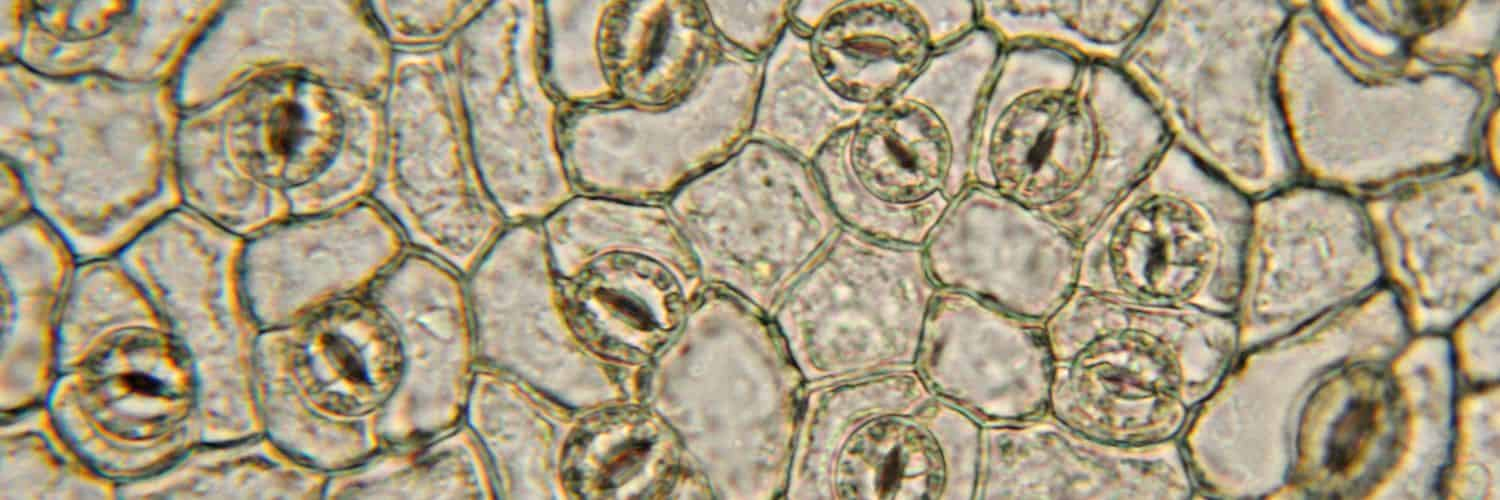

Stomata are tiny openings on the surface of leaves that play a crucial role in photosynthesis, the process by which plants convert carbon dioxide into food. Understanding how stomata work is important for harnessing the carbon-capturing abilities of plants to maximize food production and remove excess carbon dioxide from Earth’s atmosphere.

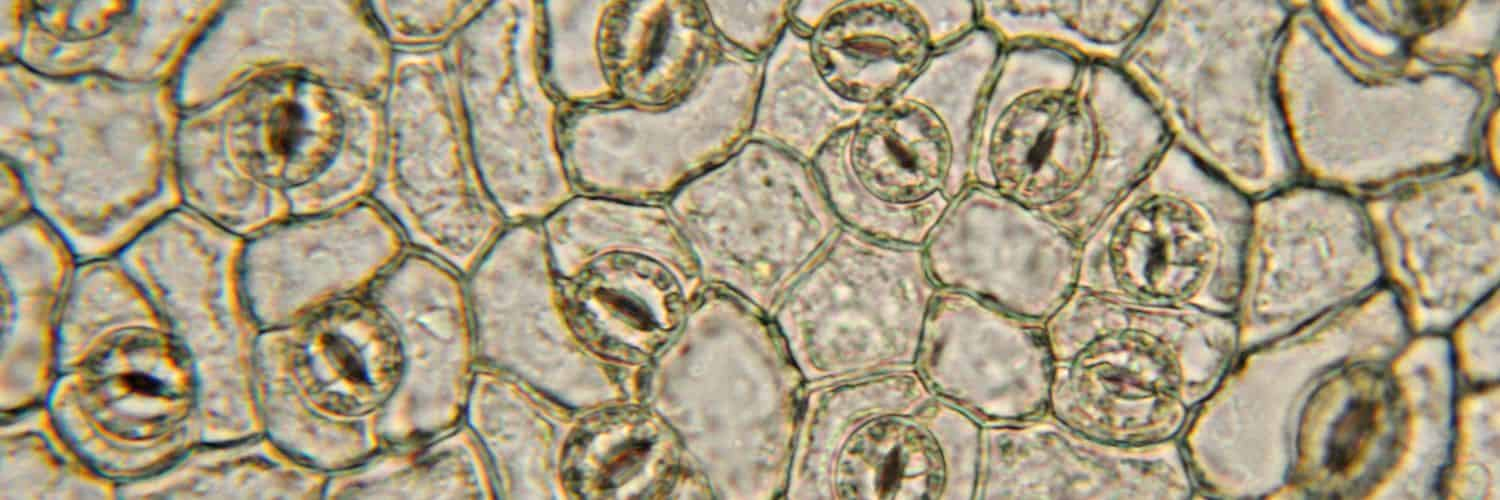

Stomata can rapidly open and close in response to their environment to maximize carbon dioxide gain and minimize water loss. This is controlled by two flanking guard cells, which are located on either side of the stomatal pore (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.Open (left) and closed (right) stomata and measurement directions. Micrograph from Plant Physiology, 2nd Edition, p. 523, edited by Taiz and Zeiger.

The opening and closing of stomata are driven by changes in the water pressure inside the guard cells. When these curved, tubular cells take up water, their internal pressure increases, causing them to swell and elongate which drives the stomatal pore to open. Conversely, when the guard cells lose water, their internal pressure decreases, leading to a shrinkage of the cells and the closing of the stomatal pore.

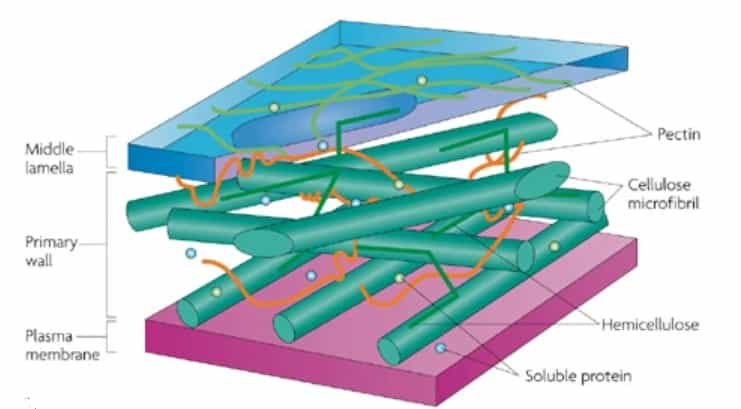

Elongation, rather than uniform expansion in all directions uniformly, is a characteristic possessed by guard cells and is crucial to stomatal function. This anisotropic (directional) expansion is attributed to the unique structure and mechanical properties of the guard cell walls. Stiff cellulose fibrils are arranged circumferentially around the cell, resulting in high stiffness and low elasticity in the circumferential direction compared to the longitudinal direction (see Figure 1). The matrix of hemicellulose and pectin, in which the cellulose fibrils are embedded, is also believed to play a role in the overall mechanical properties of the guard cell walls (see figure 2).

Despite the major role of cellulose fibrils in stomatal function, there is no consensus on the key physical properties of these fibrils, such as their length, abundance, and stiffness, or their proportional contribution. Without a clear understanding of these fundamental characteristics, it is difficult to develop effective strategies for enhancing stomatal performance.

Researchers Hojae Yi and Charles T. Anderson, both at Penn State University, investigated how the composition and structure of guard cell walls affected their mechanical anisotropy. This work is published in silico Plants.

The researchers developed a model of the guard cell wall, including cellulose fibrils and matrix polysaccharides, to help explain how molecular changes in wall composition and underlying architecture alter wall biomechanics in guard cells. The biomechanics were measured as the deformation (strain) and stiffness (modulus) of the cell wall in longitudinal, circumferential, and radial directions. They predicted the ability of the cell wall to exhibit anisotropic behavior based on the ratio between circumferential and longitudinal stiffness.

To determine the likely values of the cellulose fibril properties, the researchers simulated a range of values for these properties as reported in the existing literature. By evaluating which property values could reproduce the observed anisotropic behavior in the guard cell wall, the researchers aimed to infer the probable lengths, abundances, and stiffnesses of the cellulose fibrils involved in stomatal function.

Cellulose Fibril Length

Based on indirect measurements, researchers have proposed that the length of these cellulose microfibrils falls within the range of 300 to 500 nanometers. By simulating the properties of cell walls with varying cellulose fibril lengths, the researchers found that lengths of 400 and 1500 nanometers could result in anisotropic behavior of the guard cell wall. However, they also determined that longer cellulose fibrils beyond 1500 nanometers would reduce the necessary flexibility for this anisotropic behavior to occur.

Cellulose Fibril Abundance

Previous work has estimated cell walls to be composed of approximatly 30% cellulose by weight. Simulations of varying cellulose fibril abundance showed that the guard cell wall could still behave anisotropically when cellulose abundance is as low as half this abundance.

Cellulose Fibril Stiffness

The published predictions of cellulose fibril stiffness values vary widely, ranging from 50 GPa to over 100 GPa. Based on their analysis, the researchers predicted that the cellulose fibril modulus is at least 100 GPa. This is because their simulations showed that 100 GPa represents the lowest stiffness value that can replicate the anisotropic behavior of the guard cell wall.

Wall Matrix Stiffness

In addition to examining the properties of cellulose fibrils, the authors also explored the role of the cell wall matrix. Again, there is no scientific consensus on the precise stiffness of the cell wall matrix, but it is estimated to range from 75 kPa to 75 MPa.

Surprisingly, the researchers’ model predicted that the guard cell wall could exhibit anisotropic behavior across a wide range of stiffness values for the cell wall matrix. This suggests that the mechanical properties of the matrix can be modulated without compromising the overall mechanical functionality of the guard cell wall, which is critical for the opening and closing of stomata.

These research findings not only help in quantifying the properties of guard cells, but they also demonstrate that plants have multiple pathways they can utilize to optimize the mechanical characteristics of the guard cell wall. Yi explains:

By engineering the cell walls of the cells surrounding stomata, we can potentially enhance the speed and efficiency of stomatal responses. This knowledge opens up possibilities for developing strategies to improve plant performance and productivity by enhancing the responsiveness and efficiency of stomatal behavior.

READ THE ARTICLE:

Hojae Yi, Charles T Anderson, Bottom-up multiscale modelling of guard cell walls reveals molecular mechanisms of stomatal biomechanics, in silico Plants, Volume 5, Issue 2, 2023, diad017, https://doi.org/10.1093/insilicoplants/diad017